The Royal Arsenal, a sprawling complex on the south bank of the Thames in Woolwich, wasn’t just a factory; it was a beating heart of British military power for nearly five centuries. Its story reflects the evolution of warfare itself, from the thunderous booms of cannons to the silent threat of nuclear weapons.

The seeds of the Royal Arsenal were sown in 1518 when a small plot of land was acquired for equipping newly built warships at Woolwich Dockyard. This ‘Gunwharf’ initially functioned as a storage facility for cannons and other armaments. However, by 1651, specialised buildings dedicated to gunpowder blending, testing, and cannonball finishing were constructed on a new site nearby. This marked the birth of the Woolwich Arsenal, and quickly became the most important armaments facility in England.

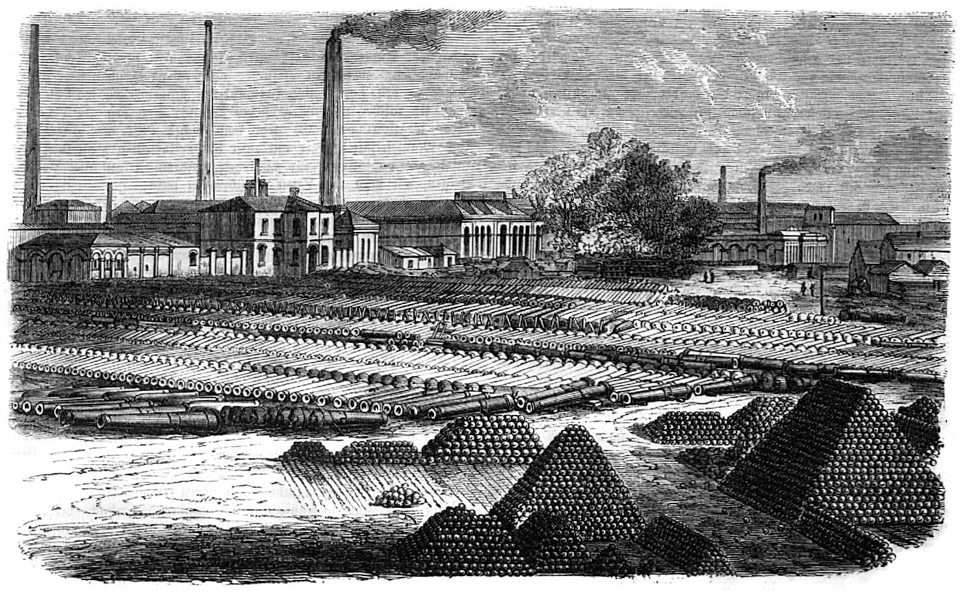

The 18th century witnessed a surge in activity. Production of guns commenced in 1720, transforming the Arsenal into a hive of activity. Foundries roared, forges glowed, and skilled workers meticulously crafted the tools of war. The establishment of the Royal Regiment of Artillery in 1720 further solidified the connection between Woolwich and military might.

An Arsenal for Empire

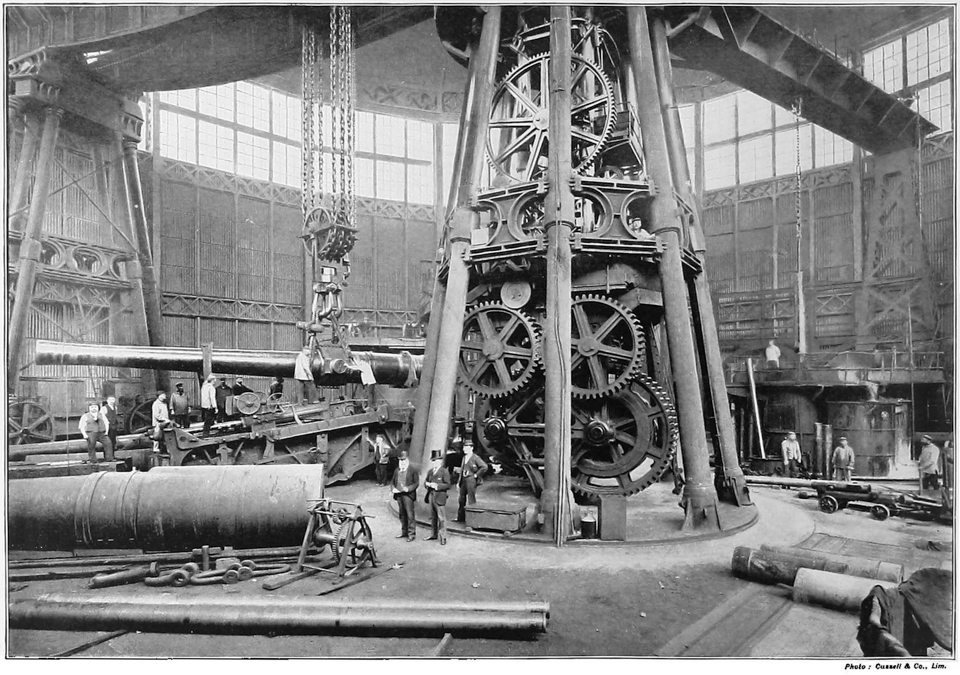

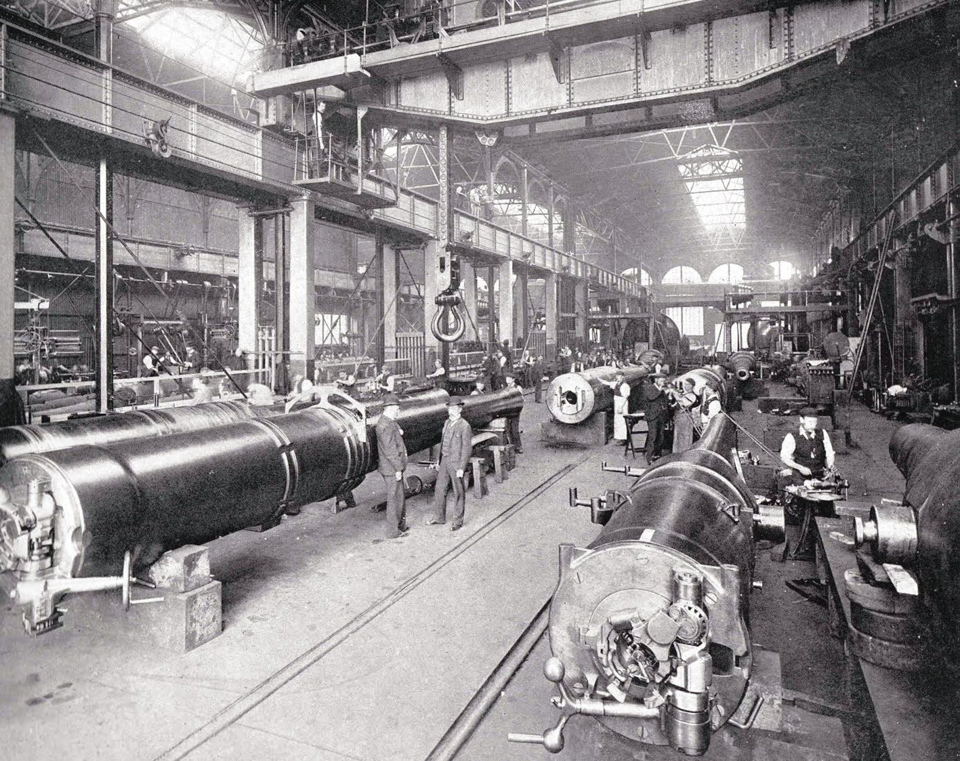

In 1805, the facility received the prestigious title Royal Arsenal. The Napoleonic wars prompted an increase of activity, and the site expanded massively with warehousing for all kinds of military equipment – one of the first integrated military stores complexes. The Arsenal embraced the new technologies of the industrial revolution, such as steam power and machine tools, to greatly increase its efficiency and productivity, – and itself became renowned centre of excellence in mechanical engineering. It was not just a factory however, but an innovator. The development of rifled artillery in the mid-19th century revolutionised battlefield tactics.

Working at the Arsenal

The Royal Arsenal workforce was a complex ecosystem. At the top sat skilled tradesmen like moulders, patternmakers, and fitters, responsible for crafting intricate weapon components. These individuals often served apprenticeships and commanded higher wages. Below them were the semi-skilled and unskilled laborers. Duties included operating heavy machinery, transporting materials, and maintaining the sprawling complex.

Work at the Arsenal was demanding, both physically and mentally. Long hours, often exceeding 60 per week, were the norm. The environment was hazardous, with constant exposure to dust, fumes, and molten metal. Industrial accidents were tragically frequent, with burns, lacerations, and even fatalities a harsh reality. Safety regulations were rudimentary at best, and workers often lacked adequate protective gear.

The harsh conditions spurred a rise in labor unrest. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed strikes demanding better wages, shorter hours, and improved safety measures. The formation of trade unions provided workers with a collective voice and the ability to negotiate with management. These efforts gradually resulted in improvements, although the dangers inherent in munitions production remained.

Lose the Arsenal, lose the war

By the early 20th century, the Royal Arsenal reached its zenith. Spanning over three miles and employing tens of thousands of workers, it was a city within a city. It had three separate railway systems with its own fleet of locomotives and rolling stock. Production lines churned out everything from shells and fuses to uniforms, tents, and supplies such as ammunition boxes.

As the battles of the First World War became immense slugging matches between ever larger guns, the army ran low on its main weapon, high explosive shells. Production needed to be increased, but labour shortages were increasing as more men were sent to the front. The result was almost 30,000 women joining the Arsenal. They worked 13 days out of 14 from 7am until 7 pm, have a day off, and then work 7pm until 7am for the next block. First used in the Arsenal’s small arms factory, women soon moved into heavy work, and danger work handling high explosives.

So great was the shift in number and nature of the workforce that nearly 3,000 new homes had to be built on the Well Hall Road and a 700-place creche – believed to be the country’s first in the workplace – was set up. Altogether, 170 million artillery shells were fired at the Germans. Despite their efforts, female workers began to be laid off even before the war ended.

Decline and transformation

The Royal Arsenal was soon regarded as crowded, out of date and dangerous in such a built-up area. By 1922, the workforce had fallen to just 6,000. Bit by bit areas and buildings were sold off, converted or demolished.

During the Second World War explosive filling work ceased on the site, but the production of guns, shells, cartridge cases and bombs continued.

Post-war technological advancements and a shift in global power dynamics led to a decline in military production. The Arsenal continued to operate for several decades, even housing a research facility for nuclear weapons during the Cold War. However, by the late 20th century, it became increasingly clear that its era was ending and in 1991 the gates finally closed.

Its legacy, however, lives on. The vast complex has undergone significant redevelopment, transforming into a vibrant hub for arts, entertainment, and creative industries. Yet, remnants of its past remain, from the imposing red-brick buildings to the Royal Artillery Museum, all serving as reminders of the pivotal role the Royal Arsenal played in shaping British history.