Canning Town is a district in the London Borough of Newham in East London. It sits on the eastern bank of the River Lea, just before it meets the Thames. The area is thought to be named after the first Viceroy of India, Charles John Canning, who suppressed the Indian Mutiny.

At the turn of the 19th century the river marked the border between London and Essex. Construction of the East India Docks was underway on the western side, while the eastern banks were a desolate marshland accessible only by boat or bridge.

Unburdened by London’s stricter planning regulations, factories producing rubber goods, sugar, flour, and chemicals sprouted up in neighbouring North Woolwich and Silvertown. The true industrial titan of Canning Town was the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company.

Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company

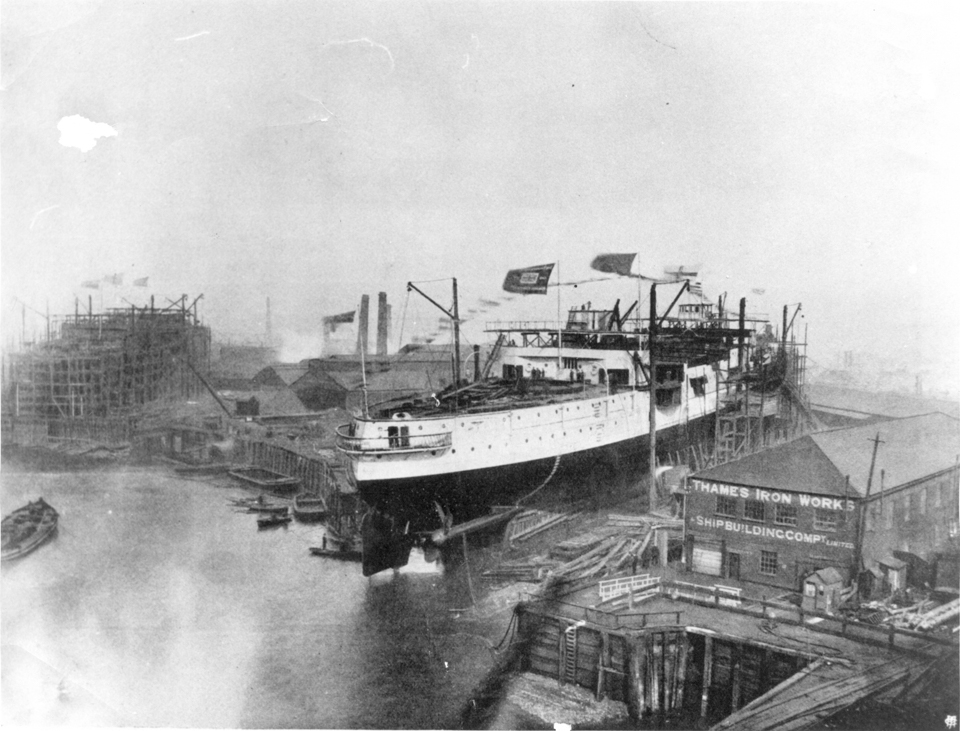

Straddling the mouth of the Lea, the Thames Ironworks pioneered iron shipbuilding in the area. The first yards were built on the west bank in 1838 with facilities on the Essex side following in 1847, which included furnaces and rolling mills. The company gradually produced larger and larger vessels, from paddle steamers to naval gunboats. In 1855 the company had more than 3,000 employees.

In 1860 it launched HMS Warrior, at the time the world’s largest warship and the first iron-hulled armoured frigate. Their success led to orders from around the world, and by 1891 the site in Canning Town occupied 30 acres. However, it was by now struggling to keep up with the shipyards of the north, with their closer supplies of coal and iron. The yard closed in 1912.

Royal Victoria Dock

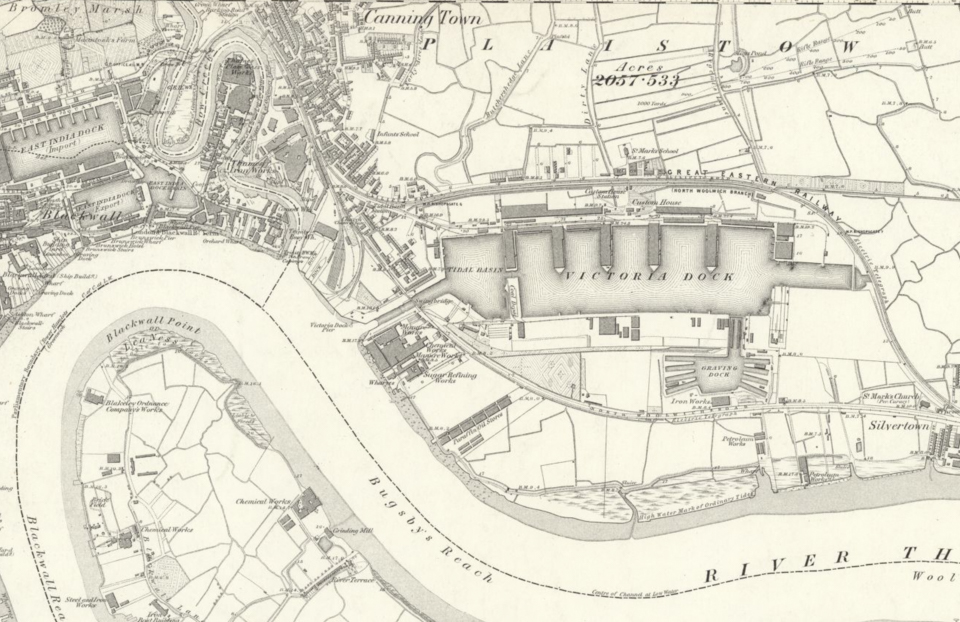

Another significant event that shaped Canning Town’s history was the opening of the Royal Victoria Dock in 1855. As the British Empire continued to expand, there was a desperate need for more docks, particularly those that could handle the new generation of steamships that were too big to be accommodated further upriver.

A group of entrepreneurs launched an ambitious plan to build vast docks that were bigger and deeper than anything that had gone before and to do so in the marshland to the east of London. After several years of construction, the docks opened in 1855. It soon became clear that more wharf space was required and so the adjacent Albert Dock opened in 1880.

Collectively they formed the largest enclosed docks in the world, with the latest technology in dockside cranes and railway lines that went straight to the dock edge. They could service hundreds of cargo and passenger ships at a time. The docks specialised in the import of food, with the rows of giant granaries and refrigerated warehouses known as the ‘warehouse of the Empire’, and in turn exported a vast range goods.

Most workers were unskilled casual labourers who carried goods between ships and quays. They were selected each morning more or less at random by foremen, making it a lottery as to whether they would get work – and pay, and food – on any particular day. The poor working and living conditions of dockworkers resulted in a series of strikes during the 1920s.

The building of Canning Town

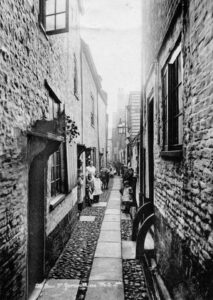

With the success of the shipyard and the opening of a railway line to North Woolwich in 1846, and the Royal Victoria Dock in 1855, Canning Town expanded rapidly and densely across Plaistow marshes. Speculative builders, attracted by the lack of planning regulations and the promise of an easy profit, began to construct cheap houses for the workers. Canning Town became notorious for its slum living conditions. There were no roads, pavements, drains or gas supply – the houses were often damp, severely overcrowded, and there was no sewerage system. Frequent floods spread sewage from the open cess pools, leading to outbreaks of smallpox and cholera. It was only after a one such epidemic in 1855 that Canning Town was given a clean water supply.

Conditions improved after 1890 when the local council was made responsible for providing decent accommodation, leading to some of the first council houses being built on Bethell Avenue. Despite their difficulties, the resident of Canning Town had a strong sense of community and culture. The area was home to many social clubs, pubs, music halls and sports teams.

The population doubled between 1881 and 1901, and by 1911 the population was nearly 300,000. From the late 19th century, a large African mariner community was established in Canning Town as a result of new shipping links to the Caribbean and West Africa. Prior to the Windrush era, Canning Town had London’s largest black population.

The Blitz and beyond

Between the wars the council sought to alleviate some of the worst aspects of housing and poverty through a programme of slum clearance and health promotion. It built about 1,200 more houses with modern facilities, along with clinics, nurseries, and a lido.

In 1940 the area became a prime target for the Luftwaffe, who believed that destroying the port would disrupt Britain’s war effort. It is estimated that some 25,000 tons of bombs fell on the docklands with over 14,000 houses destroyed during the onslaught. Despite this, the docks remained open throughout.

The destruction of some of Canning Town’s worst slum areas meant an opportunity for the rebuilding of better housing. Between 1945 and 1965 the council built around 8,000 new homes in the borough, including the Keir Hardie Estate with its schools and welfare services. As demand for housing grew the first high rise buildings were built in 1961.

Despite the damage, the Royal Docks enjoyed a brief boom in trade after the war, but it was not to last. The creation of containerised cargo required much larger ships that could not navigate as far down the Thames. Gradually the Royal Docks’ business fell into decline. The last vessel to be loaded left on 7 December 1981.

Their closure led to massive unemployment and considerable social challenges. Plans were put in place to regenerate the area. Nearby Canary Wharf was transformed into a new financial centre. London City Airport was built in the Royal Docks itself, followed by the Excel Centre.