Until the advent of air transport and the creation of the Channel Tunnel, marine transport was the only way of reaching the British Isles. For this reason, maritime trade and naval power had great importance to Britain.

My family history includes many men who served at sea, from small fishing boats to grand transatlantic liners. To provide some context for their service, this blog aims to give a brief overview of the British Merchant Navy – the collective name for British civilian ships and their crews.

Origins

In 1700 most foreign commerce was still conducted with Europe, but the next century saw a dramatic increase in overseas trade. Merchants sent out ships to trade with British colonies in North America and the West Indies. Exports consisted mainly of woollen textiles, while imports included sugar, tobacco and other tropical groceries for which there was a growing consumer demand. A triangular trade developed, whereby goods from Britain were taken to West Africa, which then loaded with slaves for transport to the West Indies and America, before returning to Britain loaded with sugar, tobacco, and cotton.

British merchants also developed trade with colonial possessions in India and the Far East, with lucrative trades in sugar, spices, and tea. They had been greatly aided by the Navigation Acts, a series of laws that stipulated that all commodity trade between Britain and its colonies should take place in British ships, manned by British seamen, and prohibiting the colonies from exporting specific products to other countries, while mandating that imports be sourced only through Britain.

By 1815, Britain possessed a global empire that was hugely impressive in scale, and stronger than that of any other European state.

The transition from sail to steam

It was the Industrial Revolution in the mid-19th century that propelled Britain to the forefront of global trade, however. The sheer quantity of raw materials to be imported – and manufactured goods to be exported – required an efficient and expansive maritime network.

Technological innovation in shipbuilding and navigation was at the forefront of this expansion. The advent of steam-powered vessels revolutionised maritime transport. Steamships like the SS Great Britain, launched in 1843, demonstrated the potential of iron-hulled, screw-propelled vessels. Unlike sail ships which relied on wind patterns, steam ships could maintain consistent schedules and were much faster, which was crucial for the burgeoning global trade network. Shipyards began using iron, and later steel, instead of wood to build larger ships with more cargo space.

The introduction of turbine engines, exemplified by the RMS Mauretania in 1906, allowed for even greater speed and efficiency. The adoption of wireless telegraphy improved communication at sea, enhancing the safety and coordination of maritime operations.

Alongside developments in ship technology were key infrastructure projects on land. The Suez Canal was completed in 1869 and allowed ships to avoid the long and hazardous trip around the Cape of Good Hope, reducing the journey by several weeks. Back in Britain great ports were built in London, Liverpool and Bristol amongst others, lined with warehouses connected by railways to the industrial heartland of the Empire.

By the late 19th century, ships brought goods such as coffee, tea, sugar, cotton, spices, tobacco, timber and wines from all over the world to Britain’s ports. Those ships then carried manufactured products such as textiles, clothing, machinery and household goods as export goods for overseas markets. The rise of maritime powers like Germany and the United States introduced competition that challenged British dominance, to which the government responded with subsidies and regulations.

Passenger transport

Of course, British mariners were not just manning ships that ran along the trade routes. There were huge numbers of fishing vessels and coastal freighters operating up and down Britain’s coastline.

Passenger transport developed at pace from the mid-19th century. Ferries operated across the English Channel, the Irish Sea, to the Isle of Man, to the Isle of Wight, the Isles of Scilly and to many Scottish islands. Ships have probably sailed these routes since prehistoric times. However, regular ferry services only expanded as steamships proved faster and more reliable transport.

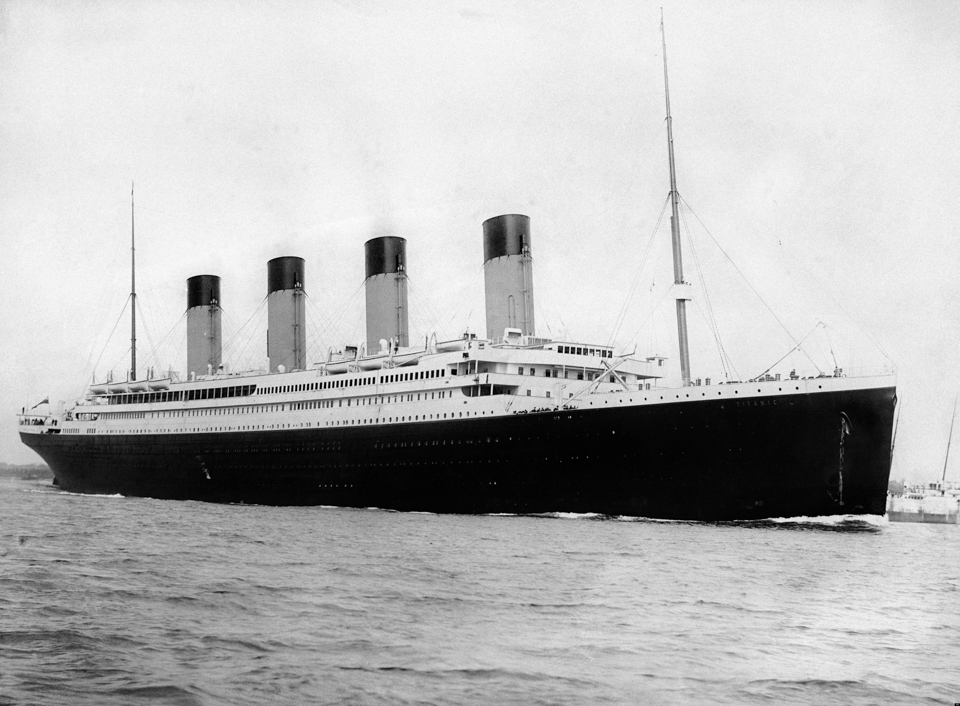

Ocean liners were the primary mode of intercontinental travel for over a century, from the mid-19th century until they began to be supplanted by airliners in the 1950s. In addition to passengers, liners carried mail and cargo. Ships contracted to carry Royal Mail used the designation RMS. The busiest route was on the North Atlantic with ships travelling between Britain and North America. It was on this route that the fastest, largest and most advanced liners travelled. There were also a wide range of routes to African and Asian colonies, Australia, and South America.

Wartime contributions

The two World Wars were a severe test for the Merchant Navy, which played a vital role in maintaining supply lines of critical equipment and food. The war highlighted its strategic importance, but also its vulnerabilities.

A policy of unrestricted warfare meant that merchant seafarers were at risk of attack from enemy ships. To counter the threat of German U-boats, the British adopted the convoy system, where merchant ships travelled in groups escorted by warships. Despite these measures, over 5,000 British merchant ships were sunk in the first war and over 45,000 mariners were killed. Most deep-water ships were sunk by torpedoes while most coastal ones hit mines or were sunk by aircraft.

Post-war reconstruction

The post-war era marked a period of transition. The advent of new technologies and the changing dynamics of global trade presented both opportunities and challenges. Excluding tankers and the US War Reserve, Britain still had the world’s largest merchant fleet in 1957. However, the emergence of ‘flags of Convenience’ to cut costs let to a rapid decline. The introduction of container shipping revolutionised the industry, improving efficiency and reducing costs.