The bustling port city of Liverpool wasn’t just a gateway to the world, it became a home for countless immigrants seeking new beginnings.

Italian immigration began in the mid-19th century. Like my own ancestors, they came first primarily from the mountainous regions around Parma and Lucca. Many were skilled organ grinders, a familiar sight on Victorian streets, often accompanied by monkeys. Others brought the sweet taste of Italy, establishing themselves as ice cream vendors. Their mobile carts, adorned with colourful designs, became a beloved fixture, offering a welcome respite from the often-gritty city life.

My family were figuristi – artists who sculpted plaster of Paris figurines and a common trade amongst the villages and towns nestled in the rolling hills of Tuscany. In the mid 19th century, the figuristi began to emigrate in ever increasing numbers. The likely reason was chain migration. One individual emigrated to another country and later returned to his family and friends as a wealthy man. Others dared to follow his example and when they also came back wealthy, others were stimulated to do the same.

It certainly was not an easy step to emigrate in these times, but as transportation improved the figuristi could go further. They began to come to Britain in increasing numbers to meet a growing demand for ornaments, from town and country houses to the most ordinary of homes. Indeed, the business of producing plaster figures became associated with Italian immigrants.

A common route was for one or two men, experienced in casting figures in moulds, to travel with up to 10 poor boys across the Apennines and the Alps. Their moulds and a few tools were sent on ahead by wagon to Chambery where they would make their first stay. They would find plaster and other simple materials for forming figures locally, with the boys dispatched throughout the city and the little towns and villages in the neighbourhood to sell the figures that had been rapidly made. Once the market had been exhausted, they would send their moulds and tools to Geneva and follow by foot, with a few figures to sell at towns and villages enroute.

They would follow a similar routine to cross France, perhaps to Fontainebleau, Paris, Amiens, and Calais, and finally to England in search of ‘a golden harvest’. These nomads sought not to settle in England but to return home with enough money to become owners of a house and a little land in the immediate neighbourhood of the villages where they were born.

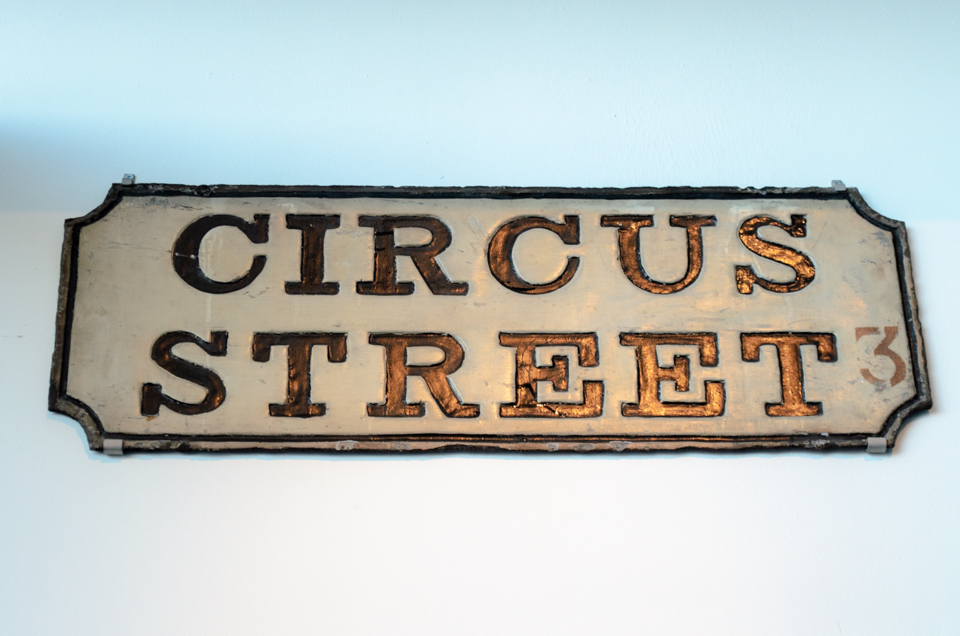

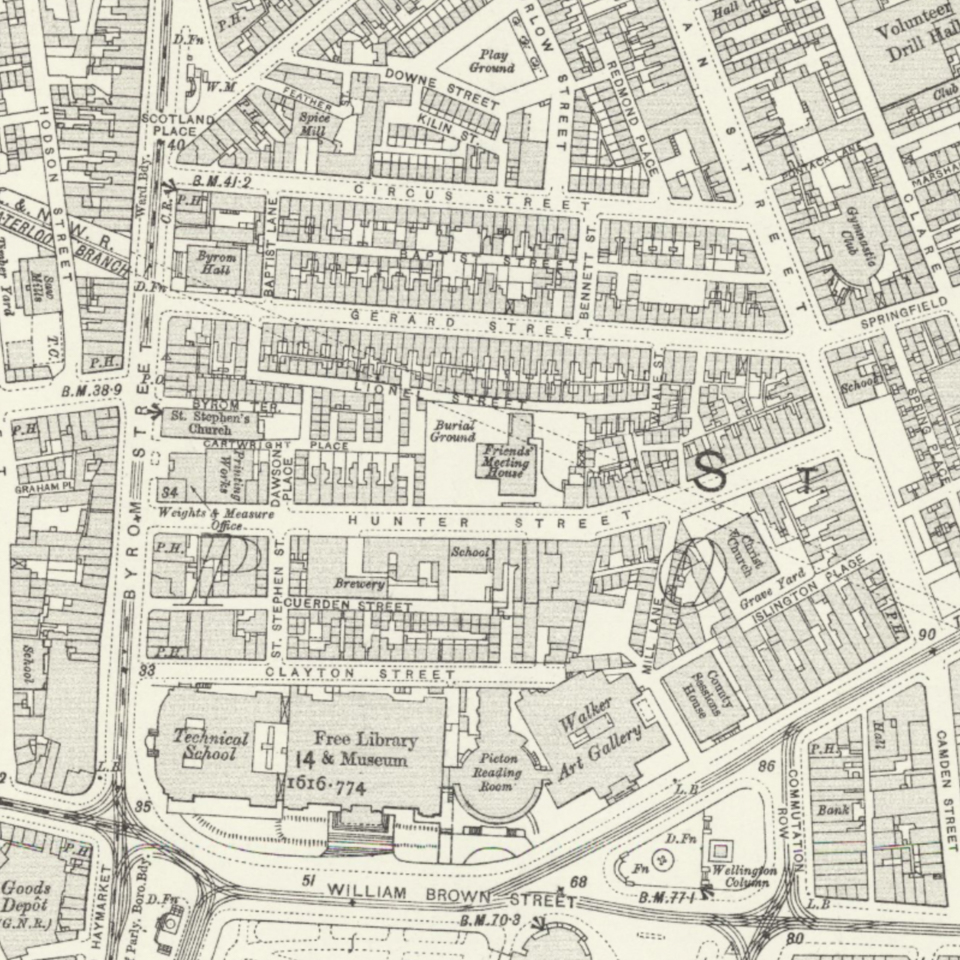

Little Italy

Some figuristi made their way to the huge bustling port of Liverpool where they lived on the cobbled streets off Scotland Road.

Laid out in the late 18th century as a main route out of the city, Scotland Road became part of the stagecoach route to Scotland. It grew into a centre of working-class life as streets of terraced and court housing were laid out either side as the city expanded.

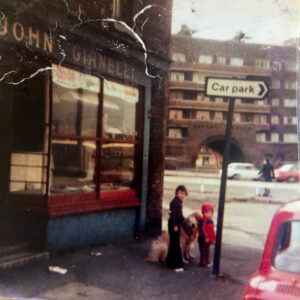

In the mid-19th century destitute, starving Irish immigrants flooded into the area during the potato famine. They were joined by an influx of Italian immigrants from 1860 to 1920.

New immigrants were welcomed with a taste of home – a simple meal called Poor Man’s Cuisine, which was a traditional pasta dish consisting of olive oil, vegetables and accompanied with a little wine. They were offered accommodation and employment, usually in the form of mosaic and terrazzo laying or entertainment. They soon prospered, enabling them to buy property and establish family businesses based on traditional Italian crafts, music, and food. Italian craftsmen were hired to create the complex intricate mosaic floors that adorn Liverpool’s civic buildings, while Italian ice-cream became famous throughout the city.

They forged a strong community of integrated prospering Italian families who maintained a traditional way of life. The Irish and Italian communities happily co-located, with both sharing a common faith. The Catholic Church acted as the hub of communal life, and a place for the younger people to meet and form relationships outside their own culture, which resulted in many Irish/Italian marriages.

Despite the happy communities, Scotland Road was densely overcrowded, with people living in courts and cellars in appalling conditions and with poverty and sickness worse than anywhere in the country.

During the 1930s much of it was declared a slum and demolished. The replacements were contemporary flats with indoor toilets, bathrooms, electricity, gas, and safe areas for children to play. With the onset of war, the Luftwaffe soon contributed to the demolition. During the 1960s and 1970s the area became victim to several developments and people were relocated to new towns on the periphery of Liverpool.