Frank had enlisted into the army in December 1915, but was not mobilised until April. He joined the 2/10th (Scottish) Battalion of The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) with service number 6856. He was described as 26 years and 325 days old, 5 feet 8 inches tall, weighing 147 lbs and being of good physical development with normal vision. The only ‘slight defect’ noted was that he had an upper dental plate.

Frank had an interesting time in the army. On 13 August 1916 while at Aldershot, he was punished by being confirmed to barracks for 10 days for an offence that is unfortunately illegible. A few weeks later he was admitted to the hospital at Connaught, Aldershot, for impetigo – a common and highly contagious skin infection that causes sores and blisters. He remained there for a full month.

Frank was then given some leave, at the end of which he chose to abscond. He was missing from 21 October until apprehended by the police in Liverpool on the 27th. For this offence he was fined seven days’ pay.

No sooner was Frank back on duty than he was in trouble again, this time for having dirty equipment during an efficiency parade. This cost him two days confined to barracks. Frank welcomed in the new year by being absent from roll call on 28 January, resulting in a further 11 days’ confinement to barracks.

The Western Front

Frank’s troubles soon got a whole lot more serious when in early 1917 the battalion was sent to the front. They sailed from Southampton in batches over a few days during the third week of February, disembarking at Le Havre. For much of the year they served in the Bois Grenier Section near Armentières with their operating base in the small town of Erquinghem a few miles to the west.

They joined the line for the first time on 26 February, suffering two casualties from shellfire during the first day, including one NCO with “shell shock”, and their first man killed two days later. Other than sporadic exchanges of shelling the lines were relatively quiet. At night they mounted routine and ‘special’ patrols, during which an officer and a handful of men would sneak up to the German trenches in an attempt to gather intelligence and sometimes take a prisoner.

The Battalion withdrew to Erquinghem for rest on 6 March. The men spent the next week undertaking drills, marches, and parades before heading back into the line. This pattern repeated for the next few months.

Frank was wounded on 28 April. The War Diary records that the Battalion had only returned to the line that day and were almost immediately subjected to heavy shelling that killed two men. Later that night a German raiding party attacked the trenches, throwing 20-30 grenades. Frank was admitted to a field hospital where he remained until 9 May. As befits his bad luck, he was wounded again just two days later, suffering a shell wound to the chin while on a working party in the rear. This must have been more serious, as he was repatriated home on 16 May.

As it turned out this was a lucky escape since in his absence the battalion fought several skirmishes with the Germans, suffering heavy casualties. Many men in the battalion witnessed the detonation of the mines under Messines Ridge on 6 June 1917, an explosion reportedly heard in London, and heard the gas bombardment of Armentières.

Return to France

Fully recovered, Frank returned to France on 13 September 1917, re-joining his unit at Flechin on 28 September. Unfortunately for poor Frank his bad luck continued, and on 20 November he was reported as missing. It was confirmed the following month that he had been captured by the enemy, becoming a prisoner of war at Dülmen.

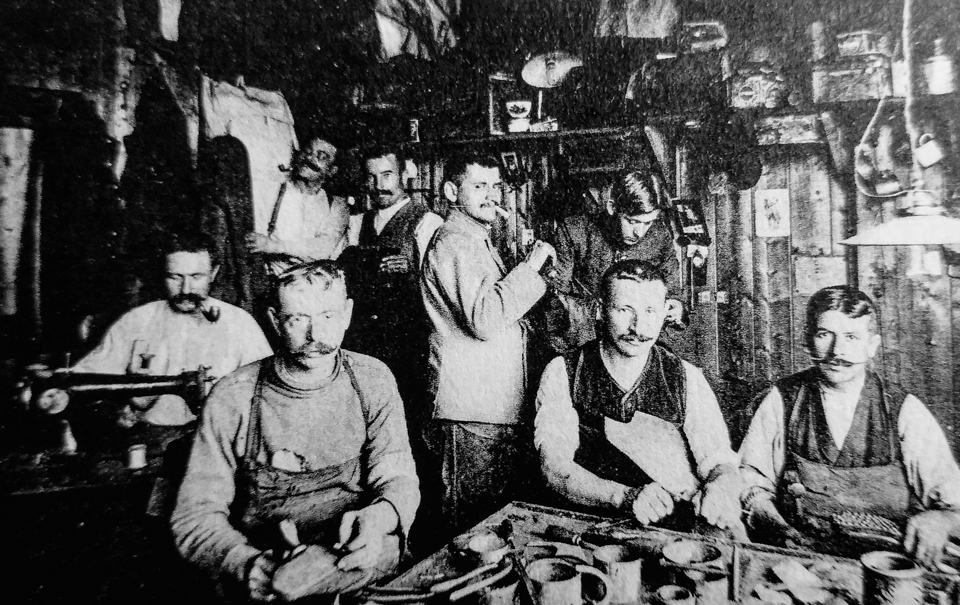

The prisoners occupied large huts, while housing 120-140 men each were still airy and clean, with small rooms for senior non-commissioned officers. The treatment of the men was generally good. Working parties left the camp about 7am and returned for a midday meal, going out again about 2pm (after two hours rest), and returning again at sundown. Parties who work at some distance from the camp had their midday meal brought to them, but they were also allowed to rest for two hours. The men are obliged to bathe once a week, but are permitted to do so more frequently. The mail, parcels, and banking arrangements are good.

Frank remained incarnated for the remainder of the war, which although unpleasant probably saved his life. He was repatriated home following the Armistice, leaving Calais on 18 November 1918.

Attempts to be discharged

Frank never saw his wife again as Catherine had died. He wrote to the army on 13 January 1919, from his new home on Kingsley Road, near Edge Hill station.

Sir, Enclosed please find application from my late employer. As a repatriated Prisoner I am due to report on the 21 Jan. While a prisoner my wife died so I would like to secure my release from the Army as early as possible. I am left with a boy 2 years of age so hoping you will oblige. I await your instructions.

The letter from his employer read:

We, Messers Percy & Sons. Ltd., 13 & 15 Seymour Street, Liverpool, hereby declare that Pte Frank Williams, 1/10 Liverpool Scottish, 30 Kingsley Road, Liverpool, was in our employment before August 4/1914, and that we are prepared to offer him employment as an agent and collector, immediately on his return to civil life.

The appeal was successful and the army replied a few days later to say that they had no objection to his immediate discharge. Despite this Frank appeared to have a little trouble when trying to follow the instructions and resulted in yet another letter being sent by him on 23 January. Unfortunately, many parts of the original handwritten letter are now illegible.

Sir, I reported myself at Seaforth at the expiration of my 2 months furlough. I was sent from the XXX XXX to the Orderly Sergeant of XXX XXX soon I got no XXX from him XXX your letter. I went to him for instructions regarding being XXX. He told me not to ask questions. What am I do, your letter stated I could start XXX before my leave expired. I would like you to look to my case. My wife died while I was a prisoner and I’ve a boy to look after. I enclose Orderly Sergeant name. I was insulted by him and I think it very hard. I feel sure I will not be the only case to bear grievance against this man.

Sir, Enclosed please find application from my late employer. As a repatriated Prisoner I am due to report on the 21 Jan. While a prisoner my wife died so I would like to secure my release from the Army as early as possible. I am left with a boy 2 years of age so hoping you will oblige. I await your instructions.

The letter seemed to have the desired effect, and on 30 January, Frank received his demobilisation papers, and was formally discharged on 27 February 1919.

Units

- 2/10th (Scottish) Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) (1916-1919)

Medals