In the mid-19th century in the period following the Crimean War there were a haphazard collection of auxiliary forces.

- The Militia was created in 1852 to supplement the regular army in defending the country against invasion and insurrection. It was administered by the Regular Army. Recruits drilled for six weeks on joining, and for one month a year thereafter. Full army pay during training and a financial retainer thereafter made a useful addition to a civilian wage, and many saw the annual camp as the equivalent of a paid holiday. 30-40% of recruits were young men who passed into the Regular Army, and only 20% served their full six-year service. Although men were not liable for service overseas, they could choose to join the Militia Reserve, accepting the liability to serve overseas with the regular army in case of war if called on to do so. The Militia was originally raised and administered on a county basis and filled by voluntary enlistment. Despite numbering 123 battalions of infantry and 32 brigades of coastal artillery, the Militia was effectively little more than a collection of independent units and not a serviceable home defence force.

- The Yeomanry consisted of 38 regiments of volunteer cavalry, which had historically been used as a form of internal security police, deployed to suppress local riots, and provide a show of force to support the authorities. Recruits were usually personally wealthy, providing their own horses and uniforms. Training requirements were low, with an annual eight-day camp.

- The Volunteers was created in 1859 amongst fears that Britain might be caught up in a wider European conflict. The lord-lieutenants of counties were authorised to create independent volunteer rifle and coastal artillery corps to defended coastal towns. Within three years it had a strength of 162,681 men, mainly drawn from the urban middle-class, training at weekends and with no annual camp. They operated independently and were mostly supported by local subscriptions and the generosity of their commanders.

The terms of service for all three auxiliaries made service overseas voluntary.

The Cardwell Reforms

The Cardwell Reforms of 1868–1872 were the first step in reforming the army. It abolished the purchase of commissions, thus professionalising the officer corps, and reformed the system of enlistment. Since the Napoleonic Wars new recruits had enlisted for 21 years, and on completion of their enlistment had the choice between discharge without pension or signing on for a further term. Although this system produced an army of experienced soldiers, it hindered recruitment and provided no pool of reserves that could be recalled in case of a national emergency.

Cardwell created a First Class Army Reserve of soldiers released from active service who had not completed their terms of service, and a Second Class Army Reserve of army pensioners and discharged soldiers with at least five years regular service. This was accompanied by a new system whereby recruits enlisted for a maximum term of 12 years. The first period was spent with the colours, and the remainder in the reserves with a short period of annual training and an obligation to serve when called up. The balance varied by branch, with the infantry serving six years with the colours and then a further six years in the reserves. The system worked, producing an immediate increase in the army’s strength. By 1900 the reservists numbered about 80,000 trained men, still relatively young and available to be recalled to their units at short notice in the event of general mobilisation.

A further part of the reforms was the reorganisation of the regimental system, linking two line regiments together with a shared depot and associated recruiting area, and bringing volunteer regiments into the regimental structure.

The Childers Reforms

In the early 1880s, the next step was taken by the Childers Reforms, who refined the structure of the infantry regiments to make them more efficient and better integrated with reserve forces. The linked regiments were amalgamated into single two-battalion regiments along with the local units of militia and volunteers. One of the line battalions served overseas while the other was stationed at home for training. The reforms effectively ended the Militia’s existence as an independent body, while authority over the Volunteers moved to the War Office.

For example, the East Surrey Regiment was an infantry regiment created in 1881:

- 1st Battalion – formerly the 31st (Huntingdonshire) Regiment of Foot

- 2nd Battalion – formerly the 70th (Surrey) Regiment of Foot

- 3rd (Militia) Battalion – formerly the 1st Royal Surrey Militia

- 4th (Militia) Battalion – formerly the 3rd Royal Surrey Militia

- 1st Surrey Rifles did not change its title when affiliated.

- 2nd Volunteer Battalion – formerly the 3rd Surrey Rifle Volunteers

- 3rd Volunteer Battalion – formerly the 5th Surrey Rifle Volunteers

- 4th Volunteer Battalion – formerly the 7th Surrey Rifle Volunteers

The men of the Army Reserve were attached to one of the line battalions, rather than being a separate numbered unit.

Effects of the Boer War

The result of these reforms was to provide a sizeable, well-trained force in the British Isles, which could be sent overseas in time of crisis, with a system of reservists and home-service volunteers to support. This is exactly what happened on the outbreak of the Boer War in October 1899.

Britain was able rapidly to assemble and effect the biggest deployment of troops since the Crimea a generation before. Nevertheless, the system immediately began to show some strain – by the end of the first year of fighting, the Regular Reserve and the Militia Reserve had been entirely exhausted.

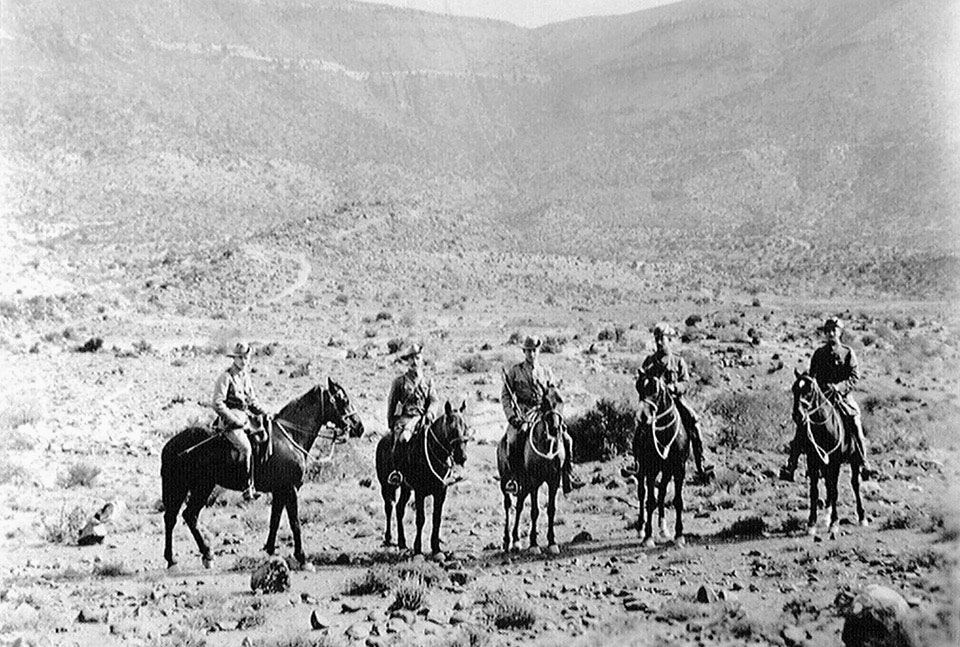

Various novel measures, including the extensive use of auxiliary forces, were experimented with for the remainder of the war: the Militia provided garrison units to free up regulars, the Volunteers sent service companies to be attached to regular battalions, and the Imperial Yeomanry was created to supply much-needed mounted infantry.

The Haldane Reforms

Amidst rising tensions in Europe, the government concluded that there was a need for a regular expeditionary force, specifically prepared and trained for use as a continental intervention force. The regular army was entirely reorganised to fit this role, and any elements which did not support it were discarded.

The war in South Africa had exposed the difficulty in relying on auxiliary forces which were not liable for service overseas as a source of reinforcements for the regular army in times of crisis. The plan was for the Volunteers, Yeomanry, and the Militia to be combined into a much larger Territorial Force to provide a second line behind the regular Expeditionary Force. Home defence now rested with the Royal Navy. It was designed well beyond the obvious needs of home defence, with fully established divisions, provided with field artillery, companies of engineers and crucial supply services, including medical provision. This could be partially trained in peacetime but, upon the outbreak of war, be swiftly trained to the necessary standards.

Amongst some strong political opposition some compromises were required. The result was the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907:

- The Militia was abolished and replaced by the Special Reserve, redesignated as the 3rd (Reserve) battalion in each regiment. Their role was not to go to war as a unit, but to provide drafts to the regular battalions. Reservists enlisted for six years and had to undergo six months of basic training on enlistment and three to four weeks training annually. They had an obligation to serve overseas. The standards of medical fitness were lower than for recruits to the regular infantry. Some 35,000 former militiamen (about 60%) transferred into the Special Reserve. It continually failed to attract sufficient recruits, and because of the long training requirement, those it did attract tended to be the unemployed and the young.

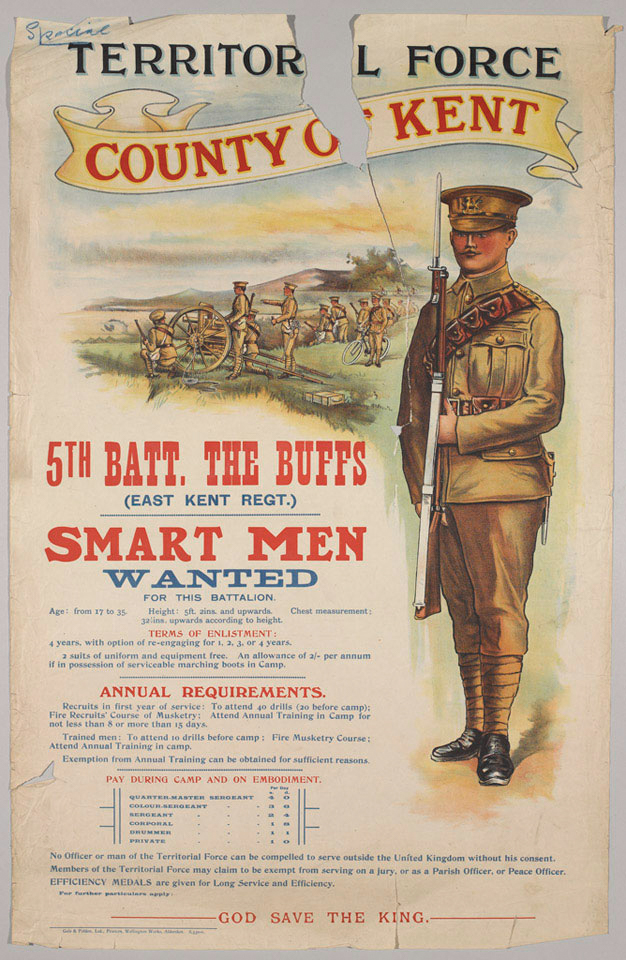

- The Territorial Force combined and re-organised the Volunteers with the Yeomanry, which became the 4th, 5th, and 6th Battalions (Territorial Force). The idea was that they would provide home defence if the army was deployed overseas. The men were liable for service anywhere in the UK but could not be compelled to serve overseas. Despite this, fewer than 40% of the men in the previous auxiliary institutions transferred into it. Recruits enlisted for four years which could be extended by an obligatory year in times of crisis. It remained a part-time form of soldiering, and they trained for one or two nights per week and earned the nickname the ‘Saturday Night Soldiers’. All members were required to attend between 8-15 days of annual camp.

Thus, the Territorial Force was designed to reinforce the regular army in expeditionary operations abroad, but because of political opposition it was assigned to home defence.

The First World War

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 saw the bulk of the changes put to the sternest of tests: the Expeditionary Force of six divisions was quickly sent to France, where, facing overwhelming odds, they secured the left flank of the French Army. Of the 90,000 members of the original BEF deployed in August, four-fifths were dead or wounded by Christmas.

Upon mobilisation in 1914, the men of the Special Reserves began to be despatched to France almost immediately. For the remainder of the war the battalions experienced a high turnover of men who were recruited, trained, and then quickly posted to make good the losses suffered by the overseas units of the regiment.

Men of the territorials volunteered for foreign service in significant numbers, allowing territorial units to be deployed to France in early 1915 to fill the gap between the near destruction of the regular army and the arrival of the New Army. Territorial units were deployed to Gallipoli in 1915 and, following the failure of that campaign, provided the bulk of the British forces in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. Other Territorial formations were dispatched to Egypt and British India and other imperial garrisons, such as Gibraltar, thereby releasing regular units for service in France. By the war’s end, the Territorial Force had fielded 23 infantry divisions and two mounted divisions.

The Territorial Force was doubled in size by creating a second line which mirrored the organisation of the original. Second-line units assumed responsibility for home defence and provided replacement drafts to the first line. They competed with the New Army for limited resources and was poorly equipped and armed.

By the war’s end, there was little to distinguish between regular, territorial and New Army formations.

Territorial Army

In 1921 the Territorial Force was renamed as the Territorial Army (TA) and re-established to be the sole means of expanding the size of the army in future wars. All recruits were required to take the general service obligation to be deployed overseas for combat. The new TA had fewer infantry battalions, while most of the yeomanry regiments converted to artillery or armoured car units or disbanded. Throughout the inter-war period they remained poorly resourced.

As Britain prepared for war in 1939, the size of the TA was suddenly increased with 88,000 men enlisted in the first four months, but there were grave shortages of instructors and equipment. Despite this, eight TA divisions were deployed before the fall of France. As the war developed, Territorial units fought in every major theatre.

After the Second World War, the TA was reconstituted with ten divisions, but then successively cut until rebuilding began in 1970, with numbers peaking at nearly 73,000. It was then run down again despite a major role in the Iraq and Afghanistan operations, bottoming at an estimated 14,000. From 2011 that trend was reversed and a new target of 30,000 trained manpower set with resourcing for training, equipment and the emphasis restored to roles for formed units and sub-units.