Liverpool is central to my family history. Over the past 200 years my ancestors have lived in almost every part of the city.

Until the 17th century the north bank of the River Mersey was mostly peaty bog with a large area given over to royal forest. There were some small fishing and farming communities, but the population was just 2,000. Silting was making passage along the River Dee to the inland port of Chester difficult however, and so efforts were made to find a new port and Liverpool was perfectly positioned.

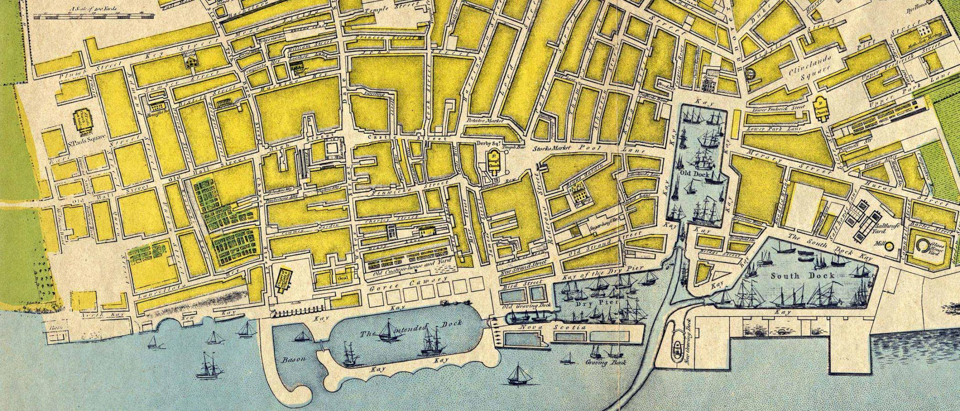

Exports of salt and coal to Ireland and imports of linen and livestock helped initial growth, but it was trade across the Atlantic that really fuelled the town’s expansion. Initially large ships had to anchor in the middle of the Mersey and thus risked being grounded and overturned at low tide. The town’s answer was the first enclosed commercial wet dock in the world, essentially building tall brick walls into the river and fitting wooden gates to maintain the water level regardless of the rise and fall of the tide. The dock opened in 1715 and could hold 100 ships. Its location in the town centre enabled traders to unload goods close to their warehouses. It was a great success and became the model for future dock development around the world.

Within 50 years the volume of shipping had doubled, and more docks were built to meet the demand. Liverpool merchants bought and sold a wide variety of goods but were also central to the growing trade in African slaves, and the vast profits transformed Liverpool into one of Britain’s most important cities. It became a financial centre beaten only by London.

Throughout the 19th century trade and population continued to expand rapidly, fuelled by the Industrial Revolution. Vast quantities of raw materials were imported from around the world, like cotton, which were then distributed by rail to the manufacturing towns of the North, before the finished goods were exported. Every crate, sack and barrel were packed and moved individually, employing more than 20,000 dockers.

Urban expansion

As the population began to rapidly grow, rich merchants moved out of the bustling centre towards the open countryside, or at least the suburbs surrounding the centre.

During the 1840s, Irish migrants began arriving by the thousands due to the Great Famine. Almost 300,000 arrived in 1847 alone, and by 1851 approximately 25% of the city was Irish born. There were other pockets of cultural diversity too. The area of Gerard, Hunter, Lionel, and Whale streets off Scotland Road were referred to as Little Italy, and there were so many Welsh that Liverpool was referred to as the Capital of North Wales.

Liverpool was granted city status in 1880, and by 1901 the population had grown to over 700,000. Its boundaries had expanded to include Kirkdale, Everton, Walton, West Derby, Toxteth and Garston.

During the early decades of the 20th century Liverpool continued to expand, pulling in immigrants from Europe. This period marked the pinnacle of its economic success. By the 1920s there were more than seven miles of docks, from Garston in the south to Bootle in the north, served by warehouses, factories, taverns, lodging houses and ships’ suppliers. Liverpool was undoubtedly ‘the second city of the Empire’.

Turbulent times: depression, war, and decline

The population peaked at over 850,000 in the 1930s but falls in world demand for the North West’s traditional export commodities contributed to stagnation and decline. Unemployment was well above the national average as early as the 1920s. The Great Depression hit Liverpool badly in the early 1930s with thousands of people in the city left unemployed. This was combated by the construction of large amounts of new council housing, creating jobs in the building, plumbing, and electrical trades. About 15% of the city’s population were rehoused in the 1920s and 1930s with more than 30,000 new council houses being built to replace the slums in the city.

During the Second World War Liverpool suffered a blitz second only to London, with no fewer than 80 air raids killing over 2,500 people. Almost half of homes sustained some damage and some 11,000 were destroyed. Significant rebuilding followed, including massive housing estates and the Seaforth Dock, the largest dock project in Britain. However, Liverpool’s docks and traditional support industries went into sharp decline with the advent of containerisation. By 1985 the population had fallen to 460,000, while the unemployment rate was one of the highest in Britain.

Townships and suburbs

Explore a brief history of the townships and suburbs which so many of my ancestors called home.