The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA), stands as one of the two regiments constituting the artillery arm of the British Army. Established in 1716, it boasts a rich history of involvement in every conflict the British Army has fought over the past three centuries.

Origins

The British Army has always used cannon, primarily supplied by temporary artillery trains assembled and disbanded on a campaign basis. Initially, only a small group of permanent gunners, overseen by the Ordnance Office, managed coastal forts, and handled equipment maintenance.

In 1716, King George I issued a Royal Warrant to create two permanent field artillery companies of 100 men each. This marked the inception of the Royal Artillery, subsequently expanding as demand for artillery support surged. Other artillery regiments were also set up at this time, such as the Royal Horse Artillery in 1793, which provided artillery support to cavalry units. Some of these other regiments were merged into the main RA, such as the Royal Irish Regiment of Artillery in 1801.

Throughout the 18th century, the RA expanded its capabilities and refined its tactics. It played a significant role in numerous conflicts, including the War of the Austrian Succession, and the Seven Years’ War. During these conflicts, artillery became increasingly integrated into combined arms tactics, working in coordination with infantry and cavalry to achieve strategic objectives.

19th century evolution

The 19th century saw the RA continue to evolve as a professional military organisation. It played a pivotal role in conflicts, including the Napoleonic Wars, Crimean War and various colonial campaigns in India and Africa. The development of new artillery tactics and strategies, coupled with advances in logistics and communication, further enhanced its effectiveness on the battlefield.

Concurrently, the Industrial Revolution brought about significant advancements in artillery technology, producing more potent and precise weaponry such as rifled guns and howitzers. These innovations revolutionised the conduct of warfare, enabling artillery to deliver devastating firepower over longer ranges with greater precision.

The first Militia Artillery units were created in 1852 to man coastal defences and fortifications in wartime, relieving the RA for active service. The RA was transferred to the British Army when the Board of Ordnance was abolished in 1855, and absorbed the artillery function of the British East India Company when it was dissolved in 1862.

20th century

In 1899, the Royal Artillery was split into three arms:

- Royal Field Artillery (RFA): focused on mobile, horse-drawn or motorised artillery supporting infantry in the field.

- Royal Horse Artillery (RHA): provided highly mobile artillery support to cavalry units.

- Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA): manned heavy guns for coastal defence and fixed fortifications.

The RHA was armed with light, mobile, horse-drawn guns that provided firepower in support of the cavalry and in practice supplemented the RFA.

Royal Field Artillery

The most numerous arm of the artillery, the horse-drawn RFA was responsible for the medium calibre guns and howitzers deployed close to the front line and was reasonably mobile. It was organised into brigades.

The RFA embraced new technologies like quick-firing guns and smokeless powder, increasing firepower and mobility. The Boer War served as a testing ground for these advancements, highlighting the importance of an agile and responsive field artillery force.

The First World War saw the RFA thrust into the heart of the brutal trench warfare. It provided crucial artillery barrages to soften enemy positions before infantry advances.

As the war progressed, the RFA adapted to the stalemate of trench warfare, developing tactics for counter-battery fire and creeping barrages. New technologies like the 18-pounder field gun offered greater accuracy and range.

Royal Garrison Artillery

The RGA was originally established to man the guns of the British Empire’s forts and fortresses, including coastal artillery batteries; the heavy gun batteries attached to each infantry division; and the guns of the siege artillery.

Fixed artillery was placed in forts and batteries in locations where they might protect potential targets such as ports and cities from attack, or from where they might prevent the advance of an enemy. However, the increasing size of battleships soon made coastal artillery redundant as they could destroy the batteries while remaining out of range.

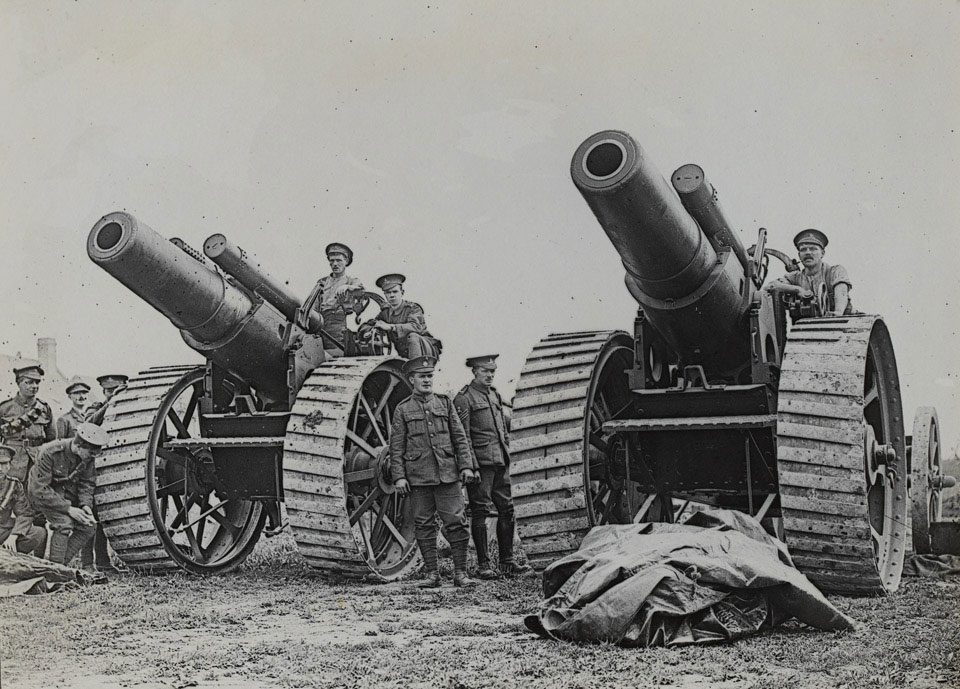

In 1914 the army possessed very little heavy artillery. As larger guns became more important, the RGA took responsibility for heavy and siege artillery in the field as its training and experience were thought to be better suited to operating larger field guns and howitzers, and they had a large body of regular and reserve personnel manning coastal batteries that for the most part were idle. The RGA grew into a very large force. Their heavy, large calibre guns and howitzers were positioned some way behind the front line and had immense destructive power.

Siege Batteries were equipped with heavy howitzers, sending large calibre high explosive shells in high trajectory, plunging fire. The usual armaments were 6-inch, 8-inch and 9.2-inch howitzers, although some had huge railway- or road-mounted 12-inch howitzers. As British artillery tactics developed, the siege batteries were most often employed in destroying or neutralising the enemy artillery, as well as putting destructive fire down on strong points, dumps, stores, roads, and railways behind enemy lines.

The RGA was often supported by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) who had devised a system where pilots could use wireless telegraphy to give corrections of aim to the guns.

The emerging need for air defence of the United Kingdom was given to the RGA and by November 1917 there were over 9,000 men manning anti-aircraft defences.

The modern RA

During the war the distinction between the RFA and RGA became increasingly blurred, and in 1924 they were merged to form the Royal Artillery once again, reflecting the need for a unified artillery force. The RHA, which has separate traditions, uniforms, and insignia, still retains a distinct identity within the regiment.

The RA was divided into brigades, which were renamed regiments in 1938. There were 960 of these regiments during the Second World War (1939-45), with over one million men.

Its size fell to 250,000 men in 1945. Since then, the RA has taken part in all of the British Army’s campaigns.

Today’s gunners use a variety of high-tech equipment, including self-propelled guns and precision rockets, as well as traditional artillery pieces.

Headquarters

Upon its creation in 1716 the two permanent field companies of artillery were quartered in the Warren (Royal Arsenal). Work on a new barracks began in 1774 on a site overlooking Woolwich Common. In 1793 the Royal Horse Artillery was formed, and a separate long barracks range was built for them.

By the turn of the century the size of the Regiment had grown substantially, and larger barracks were needed. Between in 1802-05 the compound was more than doubled in size to house over 3,000 men and 1,000 horses.

In 1939 troops were moved out of the barracks, which was vulnerable to air attack and parts of it were damaged during the Blitz. In 1956, the decision was taken that the RA would retain the barracks as their depot, but with everything behind the south front demolished and rebuilt. Over the next decade twelve new three-storey barrack blocks were erected on the site.

In 2003 the RA moved to Larkhill on Salisbury Plain (where the Royal School of Artillery has been based since 1915) and after very nearly 300 years in Woolwich, the last Artillery regiment left the barracks in July 2007.

Roles

Gunners formed the heart of the artillery unit, responsible for the direct operation and maintenance of the cannons. Their duties likely involved tasks like preparing the cannons for firing, aiming, loading the guns with ammunition (cannonballs, gunpowder bags etc.), and ultimately firing them. They were also responsible for cleaning and maintaining the artillery pieces after each use to ensure they were in proper working order for the next engagement. Gunners likely received training in basic ballistics, understanding the trajectory of cannonballs and how to adjust the cannons for different firing ranges and targets. Gunners worked together as a well-coordinated team to ensure the efficient and accurate operation of the cannons during battles or sieges.

In the 19th century, artillery pieces were primarily horse-drawn. Drivers were responsible for manoeuvring the gun carriages and ammunition wagons to and from battle positions. They needed to be skilled horsemen, able to handle multiple horses pulling heavy loads efficiently and effectively across various terrains. Drivers played a crucial role in positioning the cannons on the battlefield based on the orders of the commanding officers. They were likely responsible for caring for the horses assigned to them, ensuring they were well-fed, watered, and healthy for pulling the heavy artillery. Additionally, they might have been responsible for basic maintenance of the carriages and wagons.

In essence, gunners were the “artillery specialists” focused on operating the cannons themselves, while drivers were the logistics experts who ensured the cannons and ammunition reached the battlefield and were positioned for effective use. They were both essential cogs in the machine of 19th-century artillery warfare.