Albert enlisted into the Territorial Force on 21 January 1913 when aged 18, joining the 4th Battalion of the Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own Yorkshire Regiment (The Green Howards). On his enlistment papers he gave his occupation as a ‘labour man on the docks’ and was described as 5 feet 6 inches tall with good eyesight. He was given service number 1538 (changed during the war to 235627) and probably served with the Middlesbrough-based A or B Companies.

At the beginning of August 1914, the 4th Battalion was at Deganwy Camp in Wales for the annual divisional training. Strong rumours of impending war led to the camp being disbanded on the 3rd, and Britain declared war on Germany the following day. On the 5th, the Battalion was ordered to mobilise, with the men assembling at Northallerton. When each company had assembled it was found that only 11 men were absent, and of these, one was dead and three were at sea.

After five days they moved for a week to Newcastle and finally joined a Brigade camp at Hummersknott Park, Darlington. They were then sent to their home defence locations, such as coastal areas to watch for invasion, dockyards, and other areas of national importance. On 14 September the Battalion was moved back to Newcastle for a period of intense training. This was done in ‘marching order’, with a full pack and haversack, 120 rounds of ammunition in pouches, a full water bottle, rifle and bayonet and entrenching tool blade hanging in its case beneath the pack and its handle strapped alongside the bayonet scabbard. Cross-country attacks in artillery formation, ending in a bayonet charge, were varied with long route marches, and sometimes digging trenches. The War Office announced that if 80% of the battalion volunteered to serve abroad, it would be permitted to embark as a unit. Thus, on 24 September, Albert signed an agreement to serve in any place outside of the UK in times of National Emergency, thus removing the prior restrictions of his service. Such was the number of volunteers wanting to join the unit, that the battalion was re-designated the 1/4th, with a new 2/4th was to be formed to take over their role of home defence and train new recruits.

Arrival in France

Six months later, the order was received for the whole of the Northumbrian Division to proceed to France. The 1/4th (who we’ll now call the 4th Yorks) embarked at Folkestone on 17 April 1915, landing at Boulogne late that same evening. They spent a very cold night camped on nearby hills before marching to Desveen, from where the French Railways took them to Cassel before a final march to Godwaersvelde.

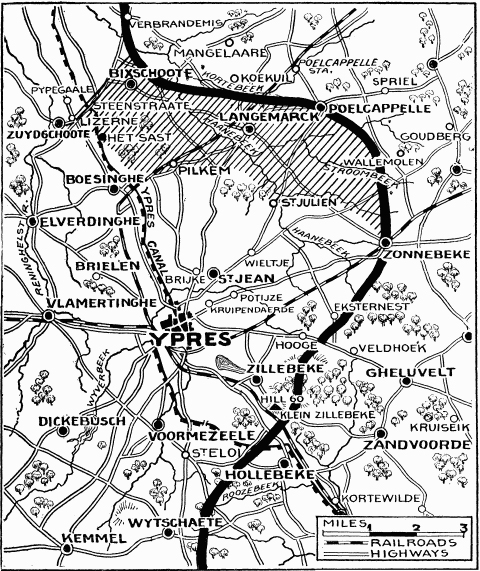

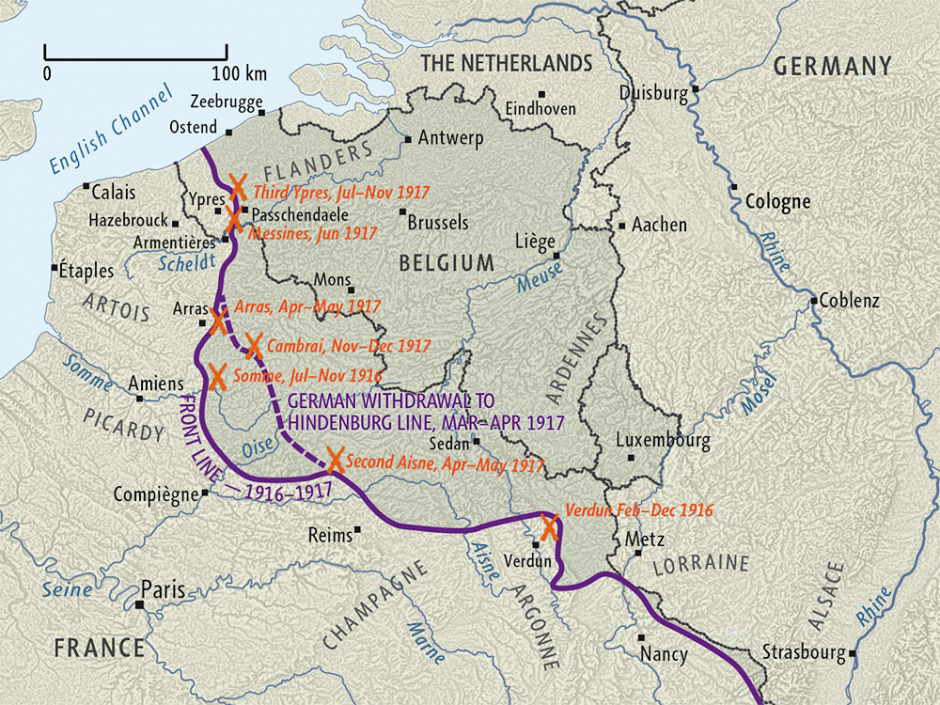

New arrivals in France normally underwent a period of further training and familiarisation with trench warfare. Instead, within a week the Germans had launched a major offensive to regain the strategic Belgian town of Ypres, which formed a major wedge in their lines (known as the Ypres Salient). The onslaught was opened on 22 April with the first use of chlorine gas over a 4-mile stretch of the front. Unprepared, the colonial French troops suffered over 6,000 casualties, many of whom died within ten minutes as the gas filled the trenches, forcing the troops to climb out into heavy enemy fire. Canadian troops prevented a complete breakthrough and then bravely charged the enemy with bayonets to regain possession of the wooded area immediately in front of the village of St Julien (see Robert Foulkes).

All British troops in the sector were pushed forward to fill dangerous gaps, with the 4th Yorks thrown forwards to the Yser Canal on the morning of 24 April. After being subjected to sporadic artillery bombardment, they crossed the canal under fire to support the 3rd Canadian Brigade. They were almost immediately ordered to attack through the village of Fortuin and then on to the village of St Julien, where the Canadians had been overrun following another chlorine gas attack. They encountered the German advance head-on, and without artillery support helped drive the Germans back to the village. Casualties were severe, but they had prevented the Germans from making any further advance.

They were withdrawn the following day. On 28 April, after a few days’ rest, they were ordered to relieve the 5th Yorks in trenches on the Northern side of the Fortuin to Passchendaele Road, arriving two days later. While units such as the 4th Yorks were holding the Germans, others were furiously digging a new line of trenches to which all troops withdrew on the night of 3 May. In the interim the Battalion had been continually bombarded with both shells and gas, causing several casualties. They were soon withdrawn for some much-needed rest, although they continued to suffer casualties from shelling. At this time the Northumbrian Division was reorganised, with the 4th Yorks joining the 150th (York and Durham) Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division.

Battle of Bellewaarde

On 23 May the 4th Yorks were sent with the 9th Lancers to defend the position astride the Menin Road at Hooge. The following day the Germans launched a very heavy bombardment with poison gas, but the onslaught that followed was repulsed with heavy casualties. The Battalion was withdrawn the next day, having been at the centre of the gas attack and with all men suffering from it to some extent. They had suffered over 200 killed and wounded. Indeed, in the six weeks from embarkation to the end of May, the 50th Division had sustained terrible losses.

Quiet period

The 4th Yorks now settled into what was to become the familiar pattern of trench warfare. Periods manning the trenches on the line involved undertaking patrols, mounting raids, and forming working parties to maintain and repair the trenches, while all the time suffering sporadic bombardments and casualties. This was intertwined with periods back in reserve, where they spent time resting, training and more working parties. They manned quiet sections of the line between Messines and Wytschaete in July before moving on to Armentieres for three months. Continual artillery and sniper fire still caused several casualties.

In the middle of November the battalion marched the 12 miles from Armentieres to Merris for a month of training. They were housed in comfortable farmhouses, and amongst the drills and parades there was time for some leisure activities such as football and a sports day. Training ended on 18 December 1915, when the troops were transported to Dickebusch, to the south of Ypres.

They settled into another three-month spell on the line, in the area around Armagh Wood. The weather was terrible, and the trenches were fowl and overrun with rats, all the while the Germans shelled their positions, sometimes with gas. Maintaining field fortifications was an endless task, as trenches flooded and collapsed, dugouts were swamped, and communications were cut. Immediate repairs were necessary but had to be done at night, under constant harassing fire.

Mining and countermining were constant, which kept trench garrisons under permanent strain, in fear of explosions which could occur anywhere without warning. One such explosion occurred on 14 February 1916. The 4th Yorks had taken over the trenches at Hill 60 two days before, a 45m high man-made mound that was the result of a nearby railway cutting. Although the explosion caused many casualties, the edge of the crater was held, and the men were remarkably reported to have been ‘cheerful and unshaken’. For the remainder of the month, and into March, the Battalion participated in artillery-bombardments, grenade attacks and trench mortaring to fool the Germans into believing that an attack was being prepared.

At some point during 1916 Albert was given a bounty of £15 for re-enlisting following the expiration of his original terms of service (although it is unlikely that this was voluntary since he had earlier agreed to serve abroad for the duration of hostilities). The Battalion was withdrawn at the end of March and transported to the trenches in front of Kemmel, on the very south of the Ypres Salient. They once again settled into the familiar pattern of periods on and off the line, all the time under sporadic German bombardment. 17 April marked the first anniversary of the Battalion’s arrival in France, during which they had suffered 14 officers and 163 killed with another 478 wounded or gassed.

Move to the Somme – the Battle of Flers-Courcelette

After four months on the line through a harsh winter, the Battalion was finally withdrawn at the end of April for a month of rest in the Fletre area. The men spent their time training, recuperating, and undertaking leisure activities before returning for another spell on the line. On 8 August the 50th Division was abruptly relieved from their duties at Ypres and transported south to join the great battle underway on the Somme. They were attached to III Corps of the Fourth Army.

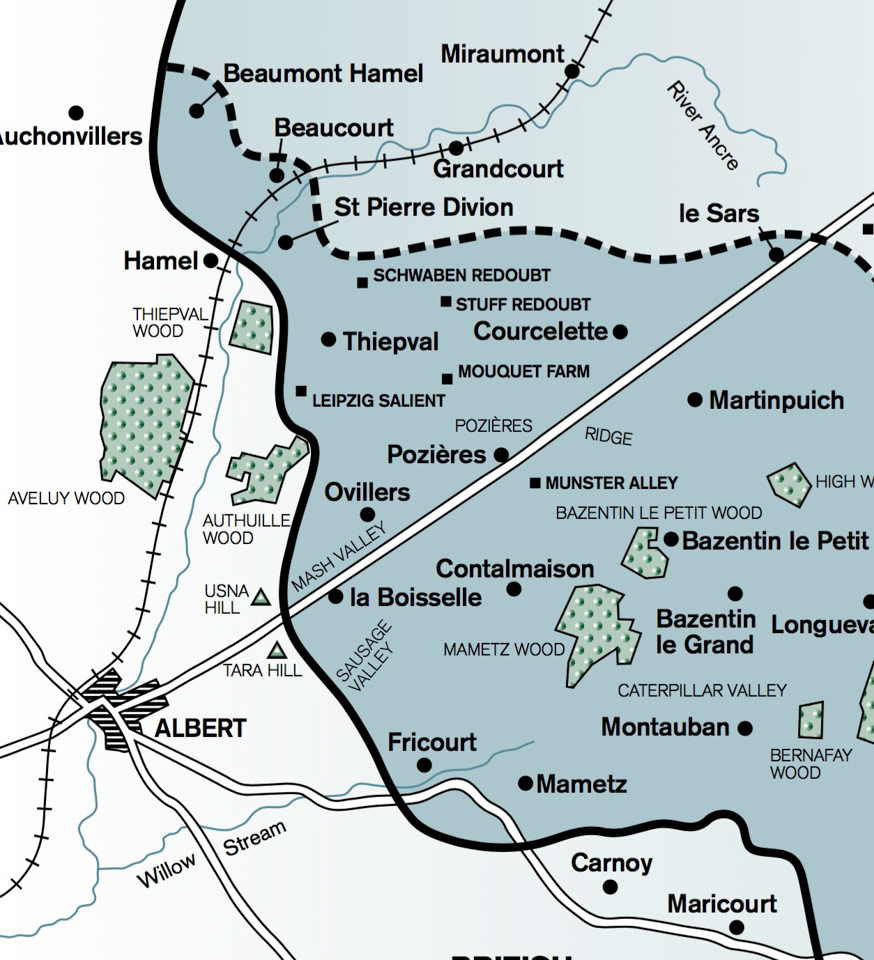

The 4th Yorks arrived at Millencourt on 17 August, a village just west of Albert in the Somme, after a long journey through primitive camps. They began a period of intensive training and drill, although hampered by unsanitary billets causing fever and diarrhoea. The Battalion departed for the trenches in front of Bazentin Le Petit on 10 September. The Battle of the Somme had been raging since the 1 July, and the men found the scene of wholesale destruction in no man’s land incomparable to that previously experienced at Ypres.

They were almost immediately thrown into the fray. Field Marshal Haig’s new ambitious plan was to cut a 3.5-mile hole in the German defences between the villages of Flers and Courcelette, allowing the cavalry to break through and roll up enemy positions from the rear, breaking the trench stalemate and enabling a push towards Arras. III Corps was assigned a sector between Flers to Martinpuich, with the assault commencing on the morning of 15 September. The infantry worked in coordination with a heavy artillery bombardment, and for the first time, tanks. The Brigade quickly gained their first objective, capturing the second within 90 minutes, and the final one by 10am. However, the 4th Yorks was positioned to the right of the advance and the Germans duly shelled their exposed flank, causing heavy casualties. The significant gains of the first day were built upon over the next few days, but a combination of poor weather and extensive German reinforcements halted the British and Canadian advance on 17 September and the Somme front reverted to an attrition struggle.

The 4th Yorks was withdrawn to the reserve at the end of the month, by which time the men were exhausted and incapable of further action. In just two weeks the battalion had lost 79 killed and 269 wounded.

Into 1917

The usual routine of trench warfare was resumed at the end of October and continued until the 4th Yorks were withdrawn to Contay in December for a month of rest and training. Once again leisure activities were organised, including a welcome Christmas dinner. The Battalion moved back to their section of the line, near Bazentin Le Petit, on New Year’s Eve. The conditions were abysmal, with trenches occupying a world of mud, disease, and dead bodies. The front was quiet however, with most casualties coming from sickness rather than the enemy. They spent February on a new section of the line 10 miles further south and near Foucaucourt, adjacent to the French area of responsibility. This was a quiet sector and there were few casualties. They would mount regular night patrols, moving from shell hole to shell hole, and sometimes encountering German patrols.

On 1 March 1917 the men of the Territorial Force received new serial numbers. The 4-digit battalion numbers were causing confusion in the administration departments, as men in different battalions had the same numbers, and thus a unique 6-digit number was issued. Albert’s service number thus changed from 1538 to 235627. On 9 March the battalion undertook a 6-mile march to Bayon Villers for 20 days of training, rest and leisure.

Second Battle of the Scarpe

Between 30 March and 12 April, the battalion moved to Arras in a journey that involved nine marches, each over 7-miles and in harsh weather. They joined VII Corps of the Third Army. Another large-scale offensive had begun there on 9 April, intended to draw German troops away from the Aisne sector some 50-miles south, where the French were to attempt a major breakthrough. The initial British attack was successful, achieving the longest advance since trench warfare had begun, but it slowed in the next few days as the German defence recovered. Meanwhile the French had been thrown back with such losses as to cause a mutiny in the ranks. The offensive was halted on 15 April to consolidate the British gains, with the 4th Yorks moving to the frontline on the 20th to take over the newly won German trenches on the ridge from Wancourt Tower to the River Cojeul.

They were shelled almost immediately with several casualties. The offensive recommenced on the 23rd (Second Battle of the Scarpe), with the 50th Division at the fore. The men went over the top behind a creeping barrage, and within half an hour had successfully taken the first German trenches in hand-to-hand combat. They pushed forward to the German support trenches, but the attacking forces on either side had suffered badly and the 4th Yorks now came under fire from three sides. The Germans were seen massing for a counterattack and without any possibility of support an orderly withdrawal was undertaken. Casualties were 363 killed, missing, and wounded. Stalemate once again ensued.

On 26 April they moved south the pleasant village of Famechon for rest and training, although this was broken between 1-4 May when they were marched to and from front for an attack that did not materialise. They moved back towards the front on 18 May, where the men spent the rest of the month resting in the spring sun at Douchy Les Ayette, before moving to Bayencourt until mid-June for further training. They returned to the line at Arras on 15 June and were gassed the very next day. The familiar routine of trench warfare once again resumed until early October. During this time Albert was granted 10 days leave from 15 September to return home.

Return to Ypres and the Second Battle of Passchendaele

From 6-25 October the 4th Yorks moved back to where they had started two and a half years before: the Ypres Salient. This had remained a quiet part of the front until another large offensive had been launched the previous June (Third Battle of Ypres). The offensive began with encouraging gains, but terrible summer weather soon bogged it down with huge loss of life. The 4th Yorks arrived on 25 October, attached to the 149th Brigade, XIV Corps, Fifth Army, and were immediately thrown into battle. As part of the plan for the Second Battle of Passchendaele, the Division was ordered to undertake diversionary activities to the extreme north of the front. The 4th Yorks was held in reserve as other battalions suffered over 1,000 men killed attacking heavily defended German positions over swampy land that was criss-crossed by streams. Over the next week the Battalion lost many men while holding the line. The offensive was abandoned in November with the capture of the little village of Passchendaele.

The routine of trench warfare resumed. The Battalion began a four-month spell on the line, which was relatively quiet at this time and there were few casualties. Three periods of rest and recuperation were spent in the popular St Omer area well behind the lines. The Battalion had left Ypres for the last time, and on 9 March the 50th Division returned to the Somme to join the Fifth Army, with the 4th Yorks based at Guillaucourt.

The Germans attack

Any hope of another quiet tour on the line was shattered on 21 March when the Germans launched a major offensive of their own along a 50-mile front in the St Quentin area, taking advantage of troops released from the east following the Russian Revolution, and in an attempt to win a decisive victory before imminent arrival of American forces. A powerful artillery bombardment was quickly followed by specially trained stormtroopers, who advanced quickly through the British lines. The 50th Division was initially held in reserve and transported to a position between the Omignon and Cologne Rivers. Retreating troops began to flood past their position the following day, quickly followed by Germans, and the battalion was forced to give some ground. The Division withdrew the following morning to a prepared line on the River Somme, with the 4th Yorks covering the withdrawal of the other battalions. They covered ten and a half miles in eight hours, all the time harassed by machine guns, artillery, and aeroplanes.

On 24 March, the exhausted men were ordered back to reinforce 24th Infantry Brigade and prevent the Germans from crossing the River Somme. Due to counterattack the following morning, they were instead themselves attacked and once again forced to withdraw. Losses amongst the three battalions of the 50th Division such that they were formed into a single composite battalion. The retreat continued until the night of 30th when the men found themselves at Boves, just to the south of Amiens. They had lost 349 killed, wounded, and missing.

The Germans had now begun to suffer severe losses as men became exhausted and communications were stretched. As the offensive on the Somme fizzled out, intelligence warned that another was being prepared to the north on the Lys. The 4th Yorks was quickly reinforced with new recruits and sent north, relieving Portuguese troops on the line to the west of the River Lys at Sailly Sur La Lys on the afternoon of 9 April. They were immediately occupied preventing the new German assault from crossing the bridge over the river, inflicting heavy casualties. They did succeed in crossing further north however, and the next day the Battalion was forced to abandon their positions, with many men taken prisoner. The Germans continued to attack in numbers, forcing a rather disorderly withdrawal over the next few days until they reached Le Parc on 13 April. The battered battalion had suffered severe casualties and were given an extended period of rest at several locations until mid-May. The following day they began another tour on the line, this time on a quiet sector at Craonne.

The end of the 4th Yorks

Albert was granted one month leave to return home from 24 May 1918. This proved to be a very lucky escape, since the Germans launched another major offensive on the 27th, with the 50th Division bearing the brunt of the attack. They suffered terribly with 87 men killed that day alone, and by the 31 May the Division had been largely decimated, with the nine battalions able to muster only 700 fighting men between them. The survivors of the 150th Brigade were formed into a single composite battalion and continued fighting through June. However, by the start of July the casualties were so great that it was impossible to find sufficient replacements. The 4th Yorks was finished as a fighting force.

When Albert returned to France, he must have been shocked to learn of the loss of his battalion. He was transferred to the 5th Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment), part of the 62nd Division, effective from 26 July, which had recently been attached to XXIII Corps of the French Fifth Army to join the Second Battle of the Marne that was raging across a wide front near Reims. They saw heavy fighting in the heavily wooded slopes of Bois de Reims. The battle was an important victory, inflicting 168,000 casualties on the Germans and marked the end of a string of German victories and the beginning of a series of Allied victories that would in three months bring the German Army to its knees.

The Hundred Days Offensive

The Battalion left the French area on 1 August, travelling by train and foot until their arrival at Authie on the 5th. This was close to the Normandy coast and well away from the front. The next day they received a large draft of 282 men. They remained here for a period of rest and training before a long 170-mile march to Saulty between 19-23 August. The following day they moved onto the line just west of the newly captured village of Courcelles. The Battalion attacked towards the villages of Behagnies and Sapignies on 25 August, which were found to be empty of the enemy, and pressed forwards until the new German trenches were found. They successfully beat off a counterattack through the Favrueil Woods later that evening. They were held in reserve for the next few days as other units pressed forward, although sporadically subjected to shelling and strafing from enemy aircraft. On the 29th the Battalion successfully attacked and captured a section of the German trenches before continuing the advance the next day. They were then held in reserve until relieved on 2 September for a period of rest.

On 10 September the Battalion marched 12 miles from the Courcelles-le-Comte area to the front at Havrincourt Wood, close to the German Hindenburg line. On the night of the 12th they made an attack towards Havrincourt village, capturing an enemy trench in hand-to-hand combat, suffering 148 casualties in the process. The trench was held until the battalion withdrew to Gomiécourt three days later, enabling other units to continue the attack. On the 27th they returned to the line at Havrincourt, and the next day successfully captured the village of Marcoing, establishing a bridgehead across the St Quentin Canal, before pressing on to raid the German trenches to take over 500 prisoners. Although they suffered over 100 killed and wounded, a private Henry Tandy of the Battalion won the Victoria Cross during this action.

After a short period of rest and some light training, they returned to the front on the 8th for a march over recently captured ground to the village of Carnieres, where they remained for a week. The war diary noted:

It was a very great pleasure to the Battalion to pass out of the devastated battle area of four year’s war and get into country free of trenches, wires etc. and to land again under cultivation.

On the evening of the 17th they moved forward to relieve another unit on the front line ahead of the village of St Python. In the early hours of the 20th the battalion crossed the wide La Selle River and cleared the village through fierce street fighting, before digging in for the night. They had killed or captured a great number of Germans for few losses. They were relieved the following day and remained in reserve until the end of the month.

The final month of the war began with a major allied offensive across the entire Western Front. On the 4 November the Battalion was tasked with capturing the high ground near Solesmes. The fighting was now in complete contrast to the trench warfare to which the troops were accustomed, fighting over open ground and house-to-house. They once again took many prisoners but suffered many casualties. They advanced 15 miles over the next few days, but with the Germans in retreat there was little opposition. The war ended at 1100 on 11 November 1918.

By the end of the war, Albert had fought in major battles at Ypres, the Somme, Arras, and Ypres again, as well as having regularly manned the lines for over three years and then participated in the final advance. It is truly remarkable that he survived, but his record shows no break in service or injuries during this time. It is of course possible that he was in a support role such as cook, signaller, or clerk, which would have provided some protection.

Albert would have to stay in the army a little longer. The Battalion left the front for the final time and marched to Charleroi in Belgium on the 23 November, where they were greeted by a band. They continued their long march, arriving at Conneux in the south of Belgium on the 30th. Early December was passed there with a routine of training in the morning followed by leisure in the afternoon, before the men once again took to the road on the 10th. After a march of over 100 miles, they finally crossed the German border, spending Christmas in the villages of Obergartzem and Firmanich, southwest of Cologne. January and February passed with the same routine of morning training and afternoon leisure. Albert was examined in the field on 27 January prior to demobilisation and was found to not have any disability of the result of his service. He was formally demobilised at York on 6 March 1919.

This narrative has drawn heavily on the truly excellent 4thyorkshires.com, which contains much more detail, maps, pictures, and personal stories from the battalion.

Units

- 4th Battalion, Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own (Yorkshire Regiment) (1913-1918)

- 5th Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) (1918-1919)

Medals