Alfred enlisted into the army on 19 February 1916, joining the 10th (Scottish) Battalion of The King’s (Liverpool Regiment). He was described as 26-years-old, 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighing 154 lbs, with a distinctive scar on the top of his chin. Given service number 357787 he was posted to the 2/10th Battalion in April 1916.

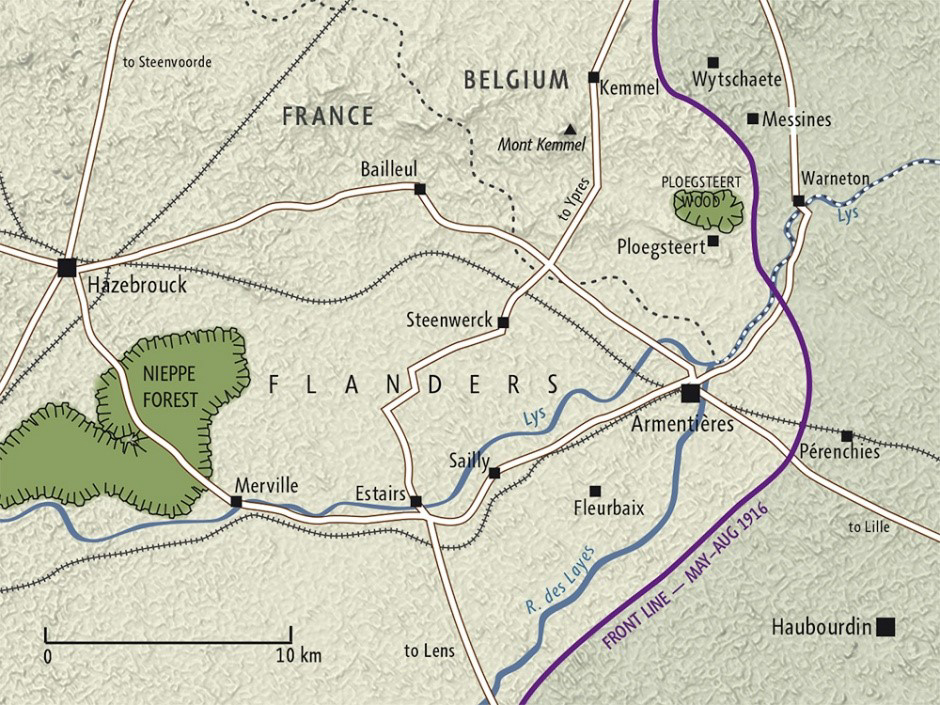

The battalion was posted to France early in February 1917, and for a description of their first few months in the field see Frank Williams. For much of the year they served in the Bois Grenier Section near Armentières with their operating base in the small town of Erquinghem a few miles to the west. They were essentially in a pattern of undertaking a spell on the lines followed by a period in camp. The former involved living in the trenches and mounting occasional night patrols in no man’s land, while the latter was a routine of drills, marches, and parades. This was generally a quiet sector of the front, although both sides regularly exchanged shellfire which caused some casualties.

Many men in the battalion witnessed the detonation of the mines under Messines Ridge on the night of 6/7 June 1917, an explosion reportedly heard in London. The war diary notes that the detonation was ‘distinctly felt’.

One famous action during this period, known as ‘Dicky’s Dash’, after Captain Alan Dickinson M.C., took place just south of Bois Grenier on the afternoon of 29 June 1917. The 161 men of C Company attacked along the line of the ‘Old Bridoux Road’ from a point in the British front line known as the Bridoux Salient. Their objective was to “destroy as many of the enemy as possible and to bring back identifications and booty”. It met with determined resistance from the enemy and although successful in gaining a foothold in the German line, met with heavy casualties in the enemy trenches and on the return to the British frontline.

At the end of October, the Battalion marched north and crossed the border into Belgium, where after a short spell on the line at Elverdinghe, just to the north of Ypres, they spent most of November and December resting at Zutkerque and Herzeele – well away from the front lines. They returned to the trenches on 29 December, taking a position on ‘Canal Bank’, near to Elverdinghe. After an uneventful week they returned to Erquinghem.

Alfred was able to return home for a period of leave between 8-21 February 1918. He returned to find the Battalion employed on working parties on the defensive line and for cable laying.

Between 1-2 April they marched about 12 miles west to Steenbecque, from where they travelled by train to Doullens, 45 miles to the south, arriving the next day. They then marched another 9 miles to Saint-Léger-lès-Authie, beginning a series of training manoeuvres in this general area that lasted until the 20th. That evening they boarded busses to travel 30 miles north to Burbure, arriving the next day. After being inspected by the Divisional General, they proceeded into the line at Festubert on the 22nd. Their stint was short, and just four days later they were relieved and moved back to encampments at Vaudricourt. On 30 April the Battalion was disbanded and absorbed into the 1/10th, who had sustained such losses during the Battle of Estaires that they virtually ceased to exist.

The new combined Battalion went straight into the line, where on 3 May Alfred was shot in the thigh and wounded, albeit not too seriously. After a period of recuperation, he re-joined his unit on 28 June, just as they were suffering an epidemic of influenza, with 200 men having to be evacuated to hospital.

Over the next few months they settled into familiar routine of manning the trenches in a relatively quiet area, suffering sporadic shelling, with raiding parties capturing a few prisoners and a couple of low-flying aircraft being brought down. This alternated with periods in reserve where time was filled with training, bathing, recreational activities, and evening concerts. This routine was abruptly ended on 3 October when the Germans began a withdrawal, and the battalion was ordered to pursue.

The war now entered its final phase with a series of Allied drives known as the Hundred Days Offensive. Four years of stalemate and trench warfare was over. The Liverpool Scottish fought one of its last actions on 5 October, suffering very heavy casualties while trying to cross La Bassée Canal. They were withdrawn and spent the two weeks recuperating and receiving replacements.

The Germans were retreating rapidly, and the Battalion was moved by train and by foot over several days from 16 October, passing through newly liberated French towns. The war diary notes:

En route, the villages were in festal attire, and national flags and bunting, which under the German regime had for so long been consigned to the ignominy of the ‘lumber room’, made gay the streets and houses. This Battn., being the first Scottish soldiers the civilians had seen, came in for particular attention. The unfamiliar skirl of the bag-pipes very quickly brought a throng of sightseers, who stared with curiosity at the swinging kilts.

John Doe

They joined the line at Froidmont on the 21st, where they suffered intermittent shelling. On 30 October there was a very heavy gas bombardment during the early hours of the morning.

The days leading up to the Armistice were spent in billets at Esplechin where there seems to have been a bit of a party atmosphere as news of the Austrian and Turkish capitulation was received and later that the Kaiser had abdicated. The days of exceptionally fine weather were filled with football matches, parades and concerts. The day before the Armistice the Battalion entered Leuze.

The reception was wonderful. The streets were overhung with flags and archways of flowers. The people lined the street, chanting and shouting ‘Vice les Anglais!’ and ‘Vive les Ecossais’ and at the same time presented the troops with flowers, cigarettes, coffee, etc. Even the nuns and monks turned out to greet us.

John Doe

On the day of the Armistice, 11 November, the Battalion was situated at Villers-Notre-Dame.

The bulk of the army remained in position until March 1919 when it could be certain that the Germans had withdrawn back behind their own borders. This time was filled with a mix of training, sports, work parties, parades, boredom, and social events. Notably on 7 December the battalion was part of the 55th Division’s guard of honour to welcome H.M. The King and the Prince of Wales at Tournai. On 15 December they moved to Sint-Job, about 19 miles west of Brussels.

In late February Alfred was given another period of leave to return home. He overstayed by 24 days and was remanded in custody on 6 April. He was given seven days Field Punishment No.2 and forfeited 17 days’ pay. He re-joined his unit on 21 April. Alfred finally returned home on 12 September 1919 for demobilisation and was formally discharged two days later. He was awarded the British War Medal and Victory Medal.

Units

2/10th (Scottish) Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) (1916-1918)

1/10th (Scottish) Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) (1918-1919)

Medals