Arthur Leslie Evans, who was commonly known by his middle name, enlisted into the army at St George’s Hall in Liverpool on 1 September 1914, just five weeks after the outbreak of war with Germany. He joined his cousin Frank Pierce in the 17th (Service) Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, which was one of the first ‘Pals Battalions’ comprising men who had enlisted on the promise that they would serve alongside their friends and neighbours rather than being arbitrarily allocated to battalions. Upon enlistment he was given service number 15776 and described as 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighing 143 lbs with a 34-inch chest, black eyes, brown hair, and a dark complexion.

News of his enlistment was featured in the Flintshire Observer on 24 September 1914:

Family’s Good Response: Alderman and Mrs J.W.M. Evans, Pendre, have both sons and three nephews who have responded to the call "Your Country Needs You." Mr G. Neville Evans has joined the Yeomanry at Birkenhead; Mr Arthur Leslie Evans, the Corn Trade "Pals" Battalion, and is now at Prescot; Lieut. Sydney Evans is with the 2nd Liverpool Rifles at Dunfermline; Mr Frank Pierce, Insurance "Pals" Battalion, Prescot; and Mr Gerald Foulkes is coming from Canada with the Colonials.

Training and deployment to France

He was billeted at Prescot Watch Factory from 14 September 1914 and trained there and also at Knowsley Hall. At the end of November he had a short spell in Whiston Hospital with influenza.

At the end of April 1915, the 17th King’s left Liverpool via Prescot Station for further training at Belton Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. They joined the 89th Brigade of the 30th Division and together moved to Larkhill in Salisbury in September. They sailed to join the Expeditionary Force in France on 7 November 1915, landing in Boulogne and moving to billets at Bellancourt, a couple of miles outside of Abbeville. The remainder of the year was spent moving around billets in this sector, from Vignacourt to Beaumetz to Puchevillers, where they undertook trenching duties.

The New Year saw the battalion take up positions on the line for the first time, manning the trenches in the Maricourt sector. They had a relatively quiet two weeks there, although some sporadic shelling caused several casualties, and after a few days rest at Suzanne repeated the experience. In mid-February the battalion was withdrawn to be used in its service role, with work parties labouring under the supervision of the Royal Engineers for the rest of the month. They took up new billets at Etinehem and settled into a routine of manning the trenches for a week at a time in a relatively quiet area, suffering sporadic artillery attacks and suffering a few casualties from enemy fire, followed by a few days of rest in reserve. Ominously on 23 May they were withdrawn to Vaux-en-Aminions where they undertook a concentrated period of training for attacks on enemy trenches.

Battle of the Somme and Liverpool’s blackest day

The battalion returned to the line in the Maricourt sector on 18 June 1916, on the extreme right of the British line, supported on their right by French troops. They noted in their war diary the sustained bombing of enemy trenches that took place from 24-30 June. The Battle of the Somme began the next day. Zero Hour was set at 7.30am and the men climbed over the top and headed forward towards their objective, the trenches in front of the village of Montauban known as ‘Dublin Trench’.

Compared to many units that were in the first wave of attacking troops that day, the 17th King’s faired remarkably well. The War Diary recorded: “The assault commenced, some shelling but very slight infantry resistance and but little machine gun fire encountered, the work of our artillery having been very effective on the German trenches.” The objective was captured by 8.30am. The diary noted that Lt. Colonel Bryan Fairfax, commanding the 17th King’s, and Commandant Lepetit commanding the adjacent French unit had advanced together across no man’s land as an act of friendship and co-operation between the two armies. The battalion remained in the trench for the next four days as the wider battle became bogged down, before being withdrawn to Bois des Tailles for rest.

The initial British attack was followed by a succession of battles to capture fortified villages and woodlands. One such objective was Trones Wood on the road to Guillemont, an area about 1.5 km long and 400m at the widest point – presenting a narrow front easier to defend than attack. The first assault was made on 8 July but was beaten back. The 17th King’s was then moved up to nearby Trigger Wood in preparation for a second assault, which began on 10 July. All four battalions of the 89th Brigade were engaged with the 17th King’s used in support. The attack failed as the battered and tangled woods provided excellent strongpoints. The battalion suffered heavy casualties until withdrawn four days later to Corbie, for rest, recuperation, and parades.

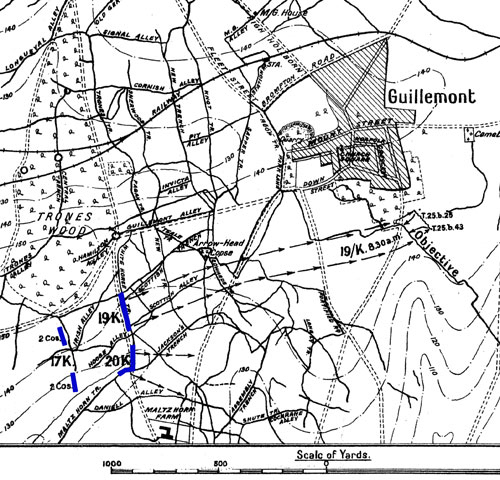

By the end of July, after three weeks of fighting, the British front had moved just 1.6 miles. The 17th King’s were moved to a camp along the Bray-Fricourt Road ready for the next attack, which was to be on the system of German trenches at Guillemont. The village had been in German hands for two years and was heavily fortified and well defended, aided by the flat land to either side. A first attack on the 23 July by the 18th King’s had failed. The second attack began on the 30th, this time with three battalions taking part (17th, 19th, 20th King’s).

They sustained casualties even before the attack as German gunners rained poison gas and explosive shells down on them in the dark as they moved up to their positions. At 4.45am the whistles blew, and they began moving towards their objective lines, south of the village, across almost a mile of no-mans-land. Thick fog made visibility and communication poor, and progress was difficult. When the fog finally began to clear, many of the advancing men were left out in the open with no cover. They were easy targets for the German machine gunners and snipers and were soon pinned down.

The men from the 19th Battalion sustained heavy losses but managed to reach their objective. Without support on their flanks, they soon came under attack from the machine gunners in the village and were forced to retreat. The 20th Battalion failed to reach their objective at all – individual companies had become disorientated in the fog and soon lost touch with each other. By mid-morning, reports made it clear the attack had been another failure and by nightfall the huge losses were apparent. Around 2,000 Liverpool Pals had been thrown forwards, of which an estimated 1,115 were killed, wounded, missing or captured (including Leslie’s cousin Frank). The battle was regarded at the time as Liverpool’s blackest day. There follows an extract from The History of the 89th Brigade written by Brigadier General Ferdinand Stanley:

Well the hour to advance came, and of all bad luck in the world it was a thick fog; so thick that you couldn’t see more than about ten yards. It was next to impossible to delay the attack – it was much too big an operation- so forward they had to go. It will give some idea when I say that on one flank we had to go 1,750 yards over big rolling country. Everyone knows what it is like to cross enclosed country which you know really well in a fog and how easy it is to lose your way. Therefore, imagine these rolling hills, with no landmarks and absolutely unknown to anyone. Is it surprising that people lost their way and lost touch with those next to them? As a matter of fact, it was wonderful the way in which many men found their way right to the place we wanted to get to. But as a connected attack it was impossible. The fog was intense it was practically impossible to keep direction and parties got split up. Owing to the heavy shelling all the Bosches had left their main trenches and were lying out in the open with snipers and machine guns in shell holes, so of course our fellows were the most easy prey. It is so awfully sad now going about and finding so many splendid fellows gone.

The Battle of Le Transloy

After Guillemont, the severely depleted Liverpool Pals had withdrawn from the Line. The 17th King’s spent all of August recuperating, moving between different camps where they undertook a variety of training and sports. They returned to the front line for the first week in September before again spending the next four weeks in intensive training, moving south to near Amiens in the process.

The British meanwhile inflicted a string of defeats on the Germans during September. By October, with winter looming, the commanders wanted to straighten out their lines by capturing Eaucourt l’Abbaye and the Flers line of defences as far as the village of Le Sars, while at the same time, a major offensive was planned towards La Transloy, Beaulencourt and Irles to have the front line on higher ground from which the offensive could be renewed in 1917. The German armies on the Somme had begun to recover from the September defeats however, with fresh divisions to replace exhausted troops and more aircraft, artillery and ammunition diverted from Verdun or stripped from other parts of the Western Front.

The attack began on 1 October but over the next week heavy rain transformed the devastated landscape of the Somme battlefield into one huge swamp. The 17th King’s did not move into forward positions until 11 October when they arrived to the northwest of Flers. The British relaunched their attack the next day, with the 17th King’s objective being to capture the German-held Gird trenches. They made it to the enemy line but were stopped by undamaged barbed wire. Coming under heavy machine gun fire from all directions, they retreated. They gained just 150 yards for 43 men killed and 230 wounded. As the War Diary records:

Attack on German front line system commenced. Enemy wire was founded to be uncut by bombardment and attack was unsuccessful. Machine gun fire was very heavy and caused many casualties. Battalion HQ and support trench was very heavily shelled. During this action all communications had to be carried out by runners and carrier pigeons, as all wires were being continually cut by enemy shelling.

The battalion moved back north towards Arras, where over the next four months they settled into a routine of 5-6 days on a quiet stretch of the front line near Humbercamps, and 5-6 days in camp undertaking training and providing working parties. On the night of 21 December, a small party that very possibly included Leslie set off to ambush a German supply line. Before they could reach their destination, they ran into a German patrol which immediately opened heavy machine gun and rifle fire at a range of just 8 yards. The party took shelter in shell holes and had to withdraw. The war diary recorded:

One member of our patrol (Pte. Evans) took shelter in a shell hole and was passed by three Germans who advanced to ascertain the damage done and then retired to enable machine gun fire to be opened down the ravine. Pte. Evans approached bodies lying on the ground and found that one man was apparently dead. Another groaned but Evans was unable to move him and had to retire.

The routine continued until 8 January when the battalion moved to Halloy for a month to construct a new railway line. The time until April was again split between periods on the front line, and periods in camp where they provided working parties for the Royal Engineers. Leslie was granted 10 days leave to return home between 4-14 February, which would be the last time that his family would see him.

The Spring Offensive

On 1 April 1917 the Battalion was moved up in preparation for the opening of the spring offensive, which was concentrated around Arras. On 8 April they moved into the assembly positions for an attack on the German trench system around Héninel, in what became known as First Battle of the Scarpe. In the event the Battalion was held in reserve and provided stretcher parties. The attack was a success and most of the objectives were achieved. The Battalion moved to Beaurains to occupy captured German trenches on 20 April, and then into the Hindenburg system two days later. In the Second Battle of the Scarpe which began on 23 April, British troops attacked along an approximate 9-mile front. The 17th was again held in reserve waiting to make an attack on Cherisy which was eventually cancelled.

The Battalion was withdrawn and moved to Fortel for rest, bathing, sports, and more training (including attack practice, rifle ranges, Lewis Guns, bombing, rifle grenades, bayonet fighting, and signalling for example). They then undertook a nine-day 50-mile march north to Ypres, taking over positions in the support trenches on 30 May where they provided working parties on the front line.

On 7 June they witnessed the huge mines being detonated under Messines Ridge which killed some 10,000 German soldiers and marked the opening of the Battle of Messines. Other battalions attacked, but the 17th was held in reserve and withdrawn to billets two days later, where the spent the rest of the month providing working parties and training. After another short spell on the line at the beginning of July, the battalion spent the remainder of the month undertaking extensive training for the next big attack, progressing from small unit training (bayonets, grenades etc.) to brigade and divisional practice attacks and field firing exercises.

Passchendaele and the Battle of Pilckem Ridge

On 30 July 1917 the battalion moved into their assembly positions for the next major offensive of the war. British positions in Belgium were based around the city of Ypres, where they occupied a bulge in the lines of trenches, known as a salient – surrounded by the Germans on three sides and overlooked by high ground, it was very vulnerable to German fire. Strategically important, it had been fought over ferociously in 1914 and 1915. After a hiatus in 1916 while the Somme offensive was fought, the plan was now to launch a major attack and force the breakthrough that would win the war. As was typical with major offensives it began with a preliminary bombardment before the first advanced under a creeping barrage. As was also typical, things almost immediately began to go wrong.

The offensive began at 3.50am on 31 July with the Battle of Pilckem Ridge. The 17th King’s, along with the 20th King’s, were in position at Maple Copse and ready to advance as part of the second wave and capture the ‘Green Line’. They moved forwards at 7.50am only to quickly discover to their surprise the enemy still in place and suffered heavy casualties. One of the leading battalions tasked with capturing the first line of trenches had got lost in the dark and reported that it had captured its objective (the ‘Blue Line’) when it had not. The 17th King’s dug in on an old German support trench just short of their objective and remained here for the next few days despite heavy shelling. 55 men were killed and 196 wounded. Further down the line the Allies were able to make some gains, but the advance was slowed by heavy rain and German counterattacks.

The broken battalion was withdrawn and spent the remainder of the month receiving replacements, resting, and training, which at one point involved passing through a gas cloud wearing their respirators.

In early September they were put back on the line near Hollebeke, to the southeast of Ypres. For the next two months they settled into a routine of moving from camp to the support area, where they would provide working and carrying parties to the front lines for five days, before taking over a position of the front line for another five days. On 4 December the 17th took up positions in the Polderhook section of the line, but during the next day Leslie was one of three men wounded when he was hit in the chest and thigh, likely by shelling. He died of his injuries at No.53 Casualty Clearing Station at Bailleul on 6 December. His commanding officer with C Company wrote of him:

I am Transport Officer of the 17th King’s and am at present home on leave, and only heard to-day the sad news of Leslie’s death. I had a letter 3 days ago from my Assistant telling me Leslie and another man had been wounded and I had hoped for the best, but a rumour I heard last night caused me to look up A. H. Blake, who, of course told me of the calamity.

I have been his officer since June 1915, and may say it is entirely due to men of his stamp that I have one of the best transports in France. He was devoted to his horses, and his turn-out was a credit to himself and to the Battalion. His conduct was exemplary during the whole time he was with me, and his cheerful disposition enabled him to rise superior to the wretchedest surroundings. I never knew a kinder boy with animals, or a more trustworthy, and I cannot adequately replace him. I feel the deepest sympathy with you all in your great loss, as it was easy to see from his letters home how close the family ties were.

Well, the poor boy has paid the greatest of all sacrifices, and we shall hope not in vain, but take consolation that he died as a soldier should, doing his duty cheerfully and bravely. His memory will always be with us, “as one of the best” and could any man have a better epitaph? If there is anything I can do, Mr. Evans, to help you in any way, please do not hesitate to let me know, and in the meantime, I am, Yours with deepest sympathy, (Signed) W. Marshall, Capt.

He is buried in the Bailleul Communal Cemetery Extension, with the personal inscription “Gone from our life but never from our hearts” and remembered on memorials at Flint House, St. Mary’s Church in Flint, and the North Wales Heroes’ Memorial Arch, Bangor.

His death was reported in the Flintshire County Herald on 14 December 1917:

It is with extreme regret that we make the sad announcement that the borough of Flint has been deprived by the death of another of its soldier heroes upon the battlefield. On Monday, Alderman J.W.M. Evans, J.P. C.C., provision merchant, Flint, and residing at Pendre, Upper Church Street, received a communication in a letter, and unofficially, that his youngest son, Private Arthur Leslie Evans, had been wounded; and further information was anxiously awaited. Another letter was to hand from the Liverpool District on Tuesday morning, corroborative of the information, and stating that Private Evans had sustained wounds while pursuing his duties. He was conveyed as speedily as possible to a dressing station so that his injuries should have the necessary attention. Hopes were entertained by those who were with him that there would be a favourable turn in his condition, and Ald. Evans and his family were also somewhat buoyed up; but early on Tuesday afternoon an official telegram arrived conveying the sad intelligence that Private Evans died on the following day. Deceased, who would have been 24 years of age on Monday next, was a native of Flint and had served a term of years with Messrs. J. Blythe and Sons, corn merchants, Bootle. He patriotically answered the call of his country and joined the Army, and had been over two years at the Front. He was home on leave from the Front in February last. He was greatly respected by his soldier comrades, and beloved by all those who shared his acquaintance in his home surroundings. The sympathies of a large number of people of Flint are extended to Alderman Evans and Mrs Evans and the members of the family in their sore bereavement.

Leslie’s personal belongings were returned to his family and included an identity disc, photographs, safety razor, fountain pen, scissors, leather purse, two pocket mirrors in a case, knife and a half-Franc note (defaced) souvenir.

Units

- 17th (Service) Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment (1914-1917

Medals