On 17 March 1900 when Peter was aged 19, he joined the local militia unit, The Wicklow Artillery (Southern Division), Royal Garrison Artillery. Although Britain – which Ireland was then part of – maintained a large standing army, it was fully employed providing garrisons in the remote colonies of the Empire. To ensure home defence, a reserve army was raised and organised on a county basis and filled by voluntary enlistment.

After 56 days of training the recruits would return to civilian life, only needing to report for 21–28 days training per year. The full army pay during training and a financial retainer thereafter made a useful addition to the men’s wage. The militia was also a significant source of recruits for the Regular Army, where men had received a taste of army life. Peter followed this route and after seven months enlisted into the Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians) in October 1900.

The Leinster Regiment had its depot in Birr and was one of eight regiments of the British Army raised largely in Ireland. Given service number 6215, Peter was described as 5 feet 5 inches tall, weighing a paltry 124 lbs (56 kgs), and with a fresh complexion, green eyes, and fair hair. After training he sailed to join the 1st Battalion in July 1901, which had been fighting in South Africa for the past year.

Boer War

Between 1899 and 1902, the British Army fought a bitter colonial war against the Boers in South Africa. Although outnumbered, the Boers were a skilled and determined enemy and were led by outstanding generals. The war had started badly for the British with several defeats in December 1899. They soon mobilised their superior resources and sent more men to South Africa. Eventually, over 400,000 soldiers were involved.

The war gradually turned Britain’s way. By the end of May 1900, the British had overrun the Orange Free State, and by October, the Transvaal had been annexed. Yet the British found that they only controlled the ground their columns physically occupied. As soon as the troops left a town or district, their control of that area faded away.

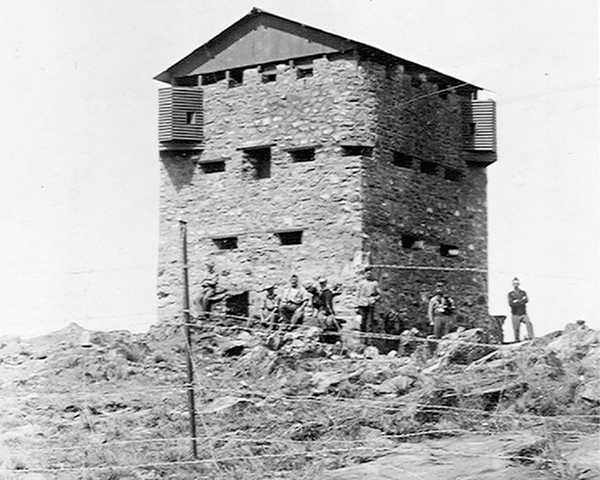

Many Boers fought on, and 18 months of cruel guerrilla warfare were to follow the annexations. To control the countryside the British built stone and corrugated iron blockhouses that were manned by permanent garrisons, connected by telephone and barbed-wire fencing. John’s 1st Battalion was left as the garrison at Vrede from October 1901 – a neighbourhood they were long to operate in. During the first five months of 1902, while other units were making a series of great drives to track down the remaining Boer guerrillas, the battalion was employed holding lines and assisting columns. They fought around Bethlehem on 8 April, losing 14 wounded.

In September 1902 Peter was posted to the Regiment’s 2nd Battalion. They were operating around Pretoria and the Central Transvaal in the final months of the war and formed part of the British garrison afterwards. Peter had a few minor problems with discipline. He was admonished in April 1903 for being drunk in camp at Petersburg and was confined to barracks for eight days in September for quitting his fatigue without permission.

Colonial policing

In January 1906 the 2nd Battalion moved from South Africa to Mauritius, then 18 months later to India. They served in the Punjab region of northern India, occupying outputs such as Jullundur (now Jalandhar), Amritsar and Dalhousie. After a few years of good behaviour, Peter found himself once again in the defaulters’ book when in February 1909 he was given 14 days detention for being drunk on duty and ‘ill-treating a comrade’. This was followed in December by 168 hours of detention for ‘highly irregular conduct’ after being caught selling false tickets for the theatre.

After three years in India the Battalion sailed home in January 1911, which was the first time that Peter had been home in a decade. He was transferred to the 1st Battalion based at Raglan Barracks in Devonport, Plymouth. On 30 March, he stole a cash box containing about £6 and was arrested some four months later. He was tried and found guilty by a civil court, being sentenced to three months imprisonment with hard labour. This spelled the end of his army career, at least so he thought, and he was discharged on 20 August.

Re-enlistment and training for war

After the outbreak of war with Germany in July 1914, Peter decided to resume his army career, and despite his prior transgressions the army was apparently happy to accept such an experienced man. Or where they? On his enlistment documents he stated that he had never served in the military and gave his age as a couple of years younger than he was. Nevertheless, he was accepted into the Royal Dublin Fusiliers with service number 12968 and posted to the 7th (Service) Battalion on 5 September. He was promoted twice, to Corporal, before the end of the month indicating that the unit was aware of his prior experience. This success was short lived however, as he was busted back down to Private on 10 October after being found drunk on active service.

The 7th (Service) Battalion had been formed at Naas in August 1914 as part of Kitchener’s First New Army and attached to the 30th Brigade in the 10th (Irish) Division. They were stationed at the Curragh and later at The Royal (Collins) Barracks in Dublin. They trained in trench warfare in Phoenix Park and in musketry at Dollymount beach. The Battalion moved to the Royal Barracks, Dublin on 2 February 1915 and then on to Basingstoke, Hampshire in May 1915. As they departed Dublin the streets were lined by crowds and spectators in the windows cheered and waved.

They underwent training in the Basingstoke area for the next three months and were inspected by King George V on 28 May and by Field Marshal, Lord Kitchener on 1 June. Peter missed both however, as he was in hospital with gonorrhoea. A few weeks later he was in trouble yet again, having missed a parade, and was given 14 days ‘Field Punishment No.2’, which could include up to two hours per day in irons, hard labour, forced marches, and regular inspections.

Gallipoli

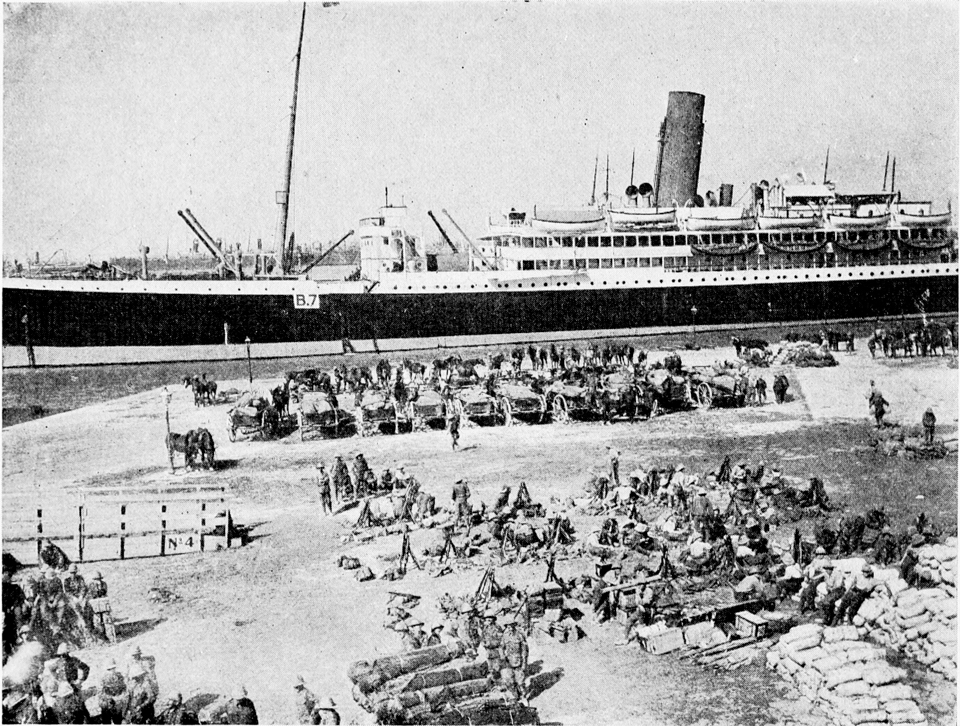

The 7th Battalion travelled to Devonport on 9 July and embarked on the Cunard liner RMS Alaunia the next morning for transport to the front. Their destination was not France however, but Gallipoli. Over the next two weeks they made stops at Gibraltar, Valletta in Malta, Alexandria in Egypt, Mudros Bay in Lemnos, and finally arrived at Mitylene on Lesbos on 25 July – to be their home for the next fortnight. The men were generally in an up-beat mood aboard the Alaunia. Good food, saltwater baths and the sea air combined to make them feel fit. Each day began with a run around the deck, and they had the luxury of ice-cold oranges from the refrigerator. Peter was evidently not as satisfied, as during the journey he tried to break away from the ship. The battalion’s war diary notes that the roll call before leaving Alexandria on 22 July found one absentee, which was presumably Peter. He was once again given 14 days ‘Field Punishment No.2’.

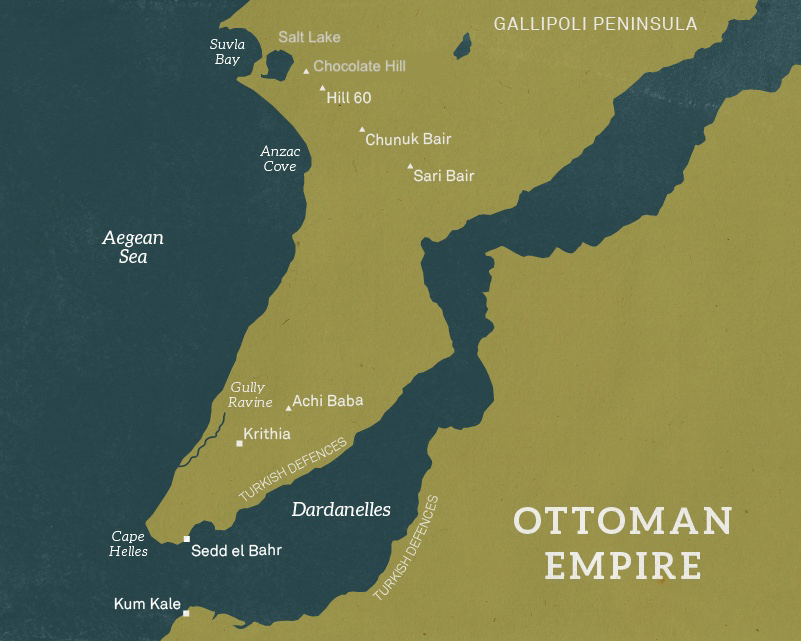

The ongoing deadlock on the Western Front led the Allies to formulate plans to attack Turkey, with the hope of relieving the pressure on Russia and at best knock it out of the war altogether. Plans were made to seize the Dardanelles – the narrow channel that led from the open sea towards the capital Constantinople. Given their strategic importance, the straits were well defended by minefields and fortifications. After naval attacks in February and March 1915 failed, it became clear that troops would have to seize the Gallipoli peninsula to the north and destroy the guns and minefields. An amphibious landing was made in April, but this was met with determined resistance and after four months of fighting little progress had been made. After receiving additional reinforcements, the British launched a new offensive on 6 August. The plan was for existing units to make a diversionary attack while new divisions were landed at Suvla Bay further to the north, with the idea of taking the hills surrounding the bay, attacking the Turks from the rear and forcing their way to a decisive victory.

The landing took place on the night of 6 August against light opposition and the beach was seized – the Turks has been caught by surprise. However, incompetent commanders failed to push on, allowing the enemy to occupy the high ground above the beaches. Peter’s 10th (Irish) Division formed part of the reinforcements landed at 7am the next morning. The men were subjected to accurate shelling as they came ashore, moving past the stretcher bearers, wounded, dying, and dead.

They took cover under the cliff and were immediately tasked with clearing some of the high ground. Alongside several other battalions they advanced towards ‘Chocolate Hill’ in the early afternoon, the hottest part of the day. The men struggled through soft mud around the edge of Salt Lake and then across the scrub covered ground. They were harassed all the way, but at 7pm when it was almost dark, they charged up the slopes with bayonets fixed and captured the crest within the hour. Throughout the night, they built defences in preparation for the inevitable counterattacks and brought forward food and water. The Battalion remained on the hill for the next five days until relieved on the night of 12/13 August.

With little progress having been made in the week since the landing, the Allies tried to force the situation by mounting an attack along the Kiretch Tepe Ridge that frames Suvla Bay. On the afternoon of 15 August elements of the 10th (Irish) Division attacked the ridge, supported by the 54th Division making an attack on ‘Kidney Hill’ to the south. The 7th Battalion was held in reserve and brought forwards after dark to relieve the exhausted attacking force, who had suffered terribly but gained the ridge. At 3.30am the Turks launched a strong counterattack in an unrelenting series of grenade and bayonet attacks. Despite terrible casualties, the 7th Dubliners refused to yield ground and were relieved at 9am. During these few hours they had lost 168 men killed and wounded. The operation was given up the next day, with over 4,000 men killed and wounded for no tactical or territorial gain.

After a short period of rest, the Battalion was involved in a minor attack on the Turkish line on 21 August with the loss of 38 more men. Thereafter they remained in the trenches for the next seven weeks as the Allies remained trapped around the beachheads, subjected to constant artillery and sniper fire. The men lived and fought in appalling conditions. Casualties from heat and disease overwhelmed the inadequate medical facilities. The Allies withdrew from the Dardanelles at the end of September. They had not moved from the beaches on which they had landed some six months previously. Over 220,000 men had been killed or wounded for no gain. The 7th Dubliners were withdrawn on the morning of 30 September and landed at Mudros a few hours later. They were to have little respite from the war however.

Salonika

Serbia was an ally of Britain and had successfully resisted the attacks of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the opening months of the war. But, in October 1915, the combined forces of Austria, Germany and Bulgaria overwhelmed her armies and conquered the country. Lack of resources and political indecision led to delays in the dispatch of help until it was effectively too late. It was eventually agreed to land a small force at the vital port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki) in the northern Greek region of Macedonia. French forces and the 10th (Irish) Division, still exhausted after service at Gallipoli, began landing at Salonika in early October. The SS Aeneas transported the 7th Battalion first to Lemnos and then on to Salonika, where they were landed on 11 October.

After receiving a large number of reinforcements to replace the men lost at Gallipoli, in the last week in October the battalion eventually went into the line in the mountains between Kosturino and Lake Doiran, just beyond the Greek frontier, as the Allies attempted to block the Bulgarian advance. Unfortunately, they had not been equipped for a winter campaign in difficult mountain terrain. The men were still dressed in shorts with pith helmets. Their health, already undermined by privations at Gallipoli, deteriorated. Hundreds suffered frostbite and exposure, hundreds more collapsed with aliments associated with debilitation, cold, and undernourishment. By the end of the month, more than 1,600 men of the 10th (Irish) Division had been evacuated.

Apart from artillery exchanges, little fighting took place until 6 December when the Bulgarians attacked following a heavy bombardment. Despite being heavily outnumbered and with inferior equipment, British units fought off several assaults on their positions over the next few days. Despite this, with Allied forces greatly outnumbers, they fell back on Salonika and were across the border by 12 December. Luckily for them, the Germans prevented the Bulgarians from continuing their advance into neutral Greece. Nevertheless, fearful of a Bulgarian assault on Salonika, and uncertain of Greek intentions, the Allies spent the first half of 1916 constructing a fortified line known as ‘The Birdcage’ in the hills around the city. This became a relatively quiet and safe corner of the war, although the men faced a boiling summer climate and many succumbed to heatstroke and malaria. Peter got himself into trouble yet again, this time for sneaking into a local village to buy beer and cognac. For this he was sentenced to two months of ‘Field Punishment No.1’, which included two hours per day with hands and feet tied to a wall or post so he could not move.

On 17 August 1916 the Bulgarians launched an offensive, which achieved early success thanks to surprise, but within two weeks the Allied forces had established a defensive line and halted the attack. On 12 September they began a counterattack of their own. The 10th (Irish) Division captured the village of Yeninkoi (Provatos today) on 30 September, but with heavy casualties. The Allies made slow and steady gains into November but didn’t have the resources to really press the case. The men now had little to do. The main enemy during 1917 was malaria, with 63,396 out of a strength of about 100,000 men hospitalised during the year.

Palestine

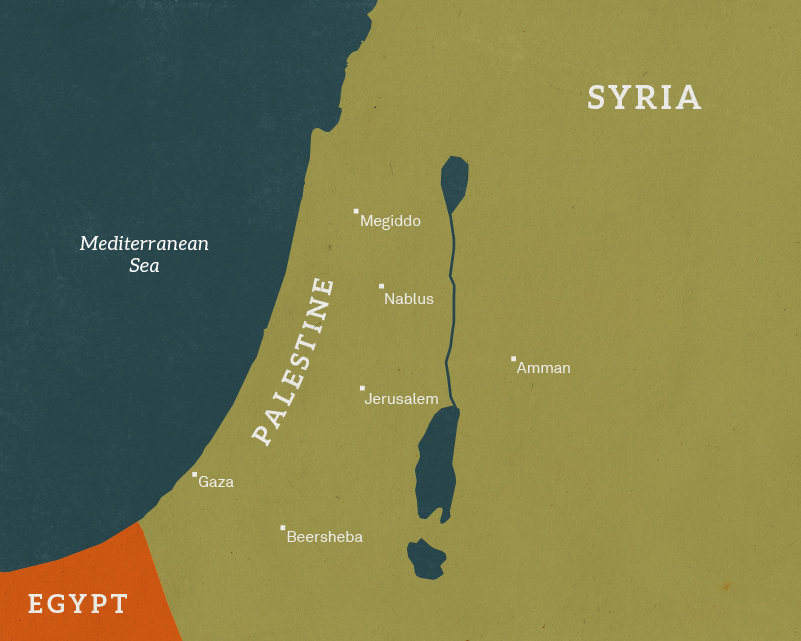

On 9 September 1917, the 10th (Irish) Division left Salonika bound for Alexandria, Egypt. They were destined for Palestine to join General Chetwode’s XX Corps of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. Some two years earlier, in February 1915, Turkish forces had attempted to breach British defences on the strategically vital Suez Canal. Seizing it would cut British communications with East Africa, India, and Asia. The British had expected the offensive and were well prepared, repulsing the attack with minimal losses. The British were initially content to guard the Suez Canal, but as loses mounted on the Western Front this manpower was much needed elsewhere. It was decided therefore to push the Turks out of the Sinai Peninsula. The newly formed Egyptian Expeditionary Force won a quick victory at Romani in May 1916, and by January 1917 had succeeded in expelling the Turks from Sinai. Boyed by the success, the Government ordered the forces to continue and capture Jerusalem.

The Turks had retired to a heavily defended line running from Gaza on the coast to Beersheba. After two unsuccessful attacks in March and April 1917, reinforcements were sent until by October 1917 they outnumbered the Turks. The British opened the new campaign by capturing Beersheba on 31 October in a surprise attack. The next blow was struck on 6 November, when all three divisions of XX Corps, including 10th (Irish) Division, successfully attacked the Kauwukah system of trenches in the centre of the Gaza to Beersheba line. The next day saw the second stage of the attack, with the 10th (Irish) Division participating in the capture of the Hareira redoubt. They then advanced along the road to Gaza. This was the final action of XX Corps due to a lack of transport.

After 10 days rest XX Corps was ordered back to the front in the Judean Hills to take over the offensive, with the 10th (Irish) Division arriving at Latron on 30 November. They immediately began to extend their lines. Other elements of XX Corps pressed on and entered Jerusalem on 11 December 1917. The Turks launched a counterattack on 26 December and for the next few days the 10th (Irish) Division supported the defence of the city.

The Western Front

The next few months were quiet for the 7th Dublins, but as losses on the Western Front mounted with the German spring offensive, the British were forced to send reinforcements from Palestine. The 10th (Irish) travelled to Kantara in early May and then sailed for Marseilles, arriving on 31 May. A few days later it was reduced to cadre strength, with surplus men absorbed into the 2nd Battalion. As the war diary makes clear however, the 7th was effectively just renamed the 2nd Battalion. The original 2nd Battalion had suffered very heavy casualties on the Somme the month before with the survivors being absorbed into the 1st Battalion.

In early June the battalion was transported north and marched to a camp near St Omer. Almost all the officers and men were suffering from malaria contracted on the Struma however, so that when they marched to their next camp at Val de Lumbres over 112 men fell out and were 20 hospitalised. Over the next six weeks, 360 men were hospitalised and evacuated, almost a third of the original strength.

At the end of June, the battalion was moved to Martin-Église near Dieppe in Normandy for a period of rest and training, with each man given four days leave to England. The next three months were spent training and parading, alongside such luxuries as saltwater swimming, hot baths, and cross-country races. During this time the Allies launched their counteroffensive against the Germans and reached the Hindenburg Line – an impregnable series of fortified redoubts, machine gun positions and fields of thick wire entanglements, 10 miles deep and 40 miles wide from Cambrai to Le Fère. It would need to be breached, and in preparation for the forthcoming attack the 2nd Dublins were moved to the front at the end of September. They joined the 149th (Northumbrian) Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division at Nurlu and were about to participate in one of the pivotal battles of the war.

A few days before their arrival, on 29 September, the Fourth Army had won a stunning victory by crossing the St Quentin Canal. The north-south canal had been incorporated within the defences of the Hindenburg Line and its capture was generally considered a suicide mission given the scale and nature of the defences. The German defenders however were exhausted and demoralised, and when faced with a daring and committed attack they offered little resistance. 4,200 prisoners were taken in a single day. The next objective in what became the wider Battle of St Quentin Canal was to clear the fortified villages behind and totally break the Hindenburg Line. The 2nd Battalion joined the line near Epehy on 2 October and were almost immediately subjected to gas shelling. They joined several successful attacks over the next few days before being withdrawn into reserve in preparation for the next push. The men knew that the open land of France lay before them, and that the nightmares of barbed wire and trenches were behind.

The retreating Germans had taken up a new position immediately to the east of the Selle River. The Fourth Army attacked on the night of the 17 October. Infantry and tanks moved forward on a 10-mile front south of Le Cateau, with the 50th Division in the thick of the action around St Benin. After crossing the river in fog, fierce fighting developed along the railway embankment. By the afternoon of the 18th the defences had been broken and the Germans driven back towards the Sambre–Oise Canal. The 2nd Battalion was then withdrawn into reserve. They had suffered 9 officers and 167 men killed and wounded. Peter Hanley was one of 20 men within the unit awarded the Military Medal for gallantry during this action.

German resistance was falling away and it was vital to keep up the momentum before winter could set in. A new attack was quickly prepared to advance along a 30-mile front. The last great concerted movement of the war, the attack was launched at 6.15am on 4 November. The Battalion was almost immediately subjected to shelling with heavy causalities but pushed on through Forêt de Mormal and captured a considerable number of Germans. They suffered 11 killed and 104 wounded. It was in this action that Peter won a second Military Medal. The Battalion continued the advance across waterlogged ground, joining successful attacks on Monceau St Waast and Flouresies on 8-9 November, their final action of the war.

The Armistice was signed on 11 November, after which the men were billeted. Peter was promoted to Lance Corporal a few days later and returned home for demobilisation in January 1919. This drew to a close a long and somewhat chequered army career. Over a period of 20 years he had fought against the Boers in South Africa, the Turks at Gallipoli and in Palestine, the Bulgars in the Balkans, and finally the Germans in France, alongside long spells of colonial policing in Mauritius and India. He had many disciplinary problems but finished his career by winning two Military Medals for valour in the space of two weeks.

Units

- The Wicklow Artillery (Southern Division), Royal Artillery (1900)

- 2nd Battalion, Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians) (1900-1911)

- 1st Battalion, Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians) (1911)

- 7th (Service) Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers (1914-1918)

- 2nd Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers (1918-1919).

Medals