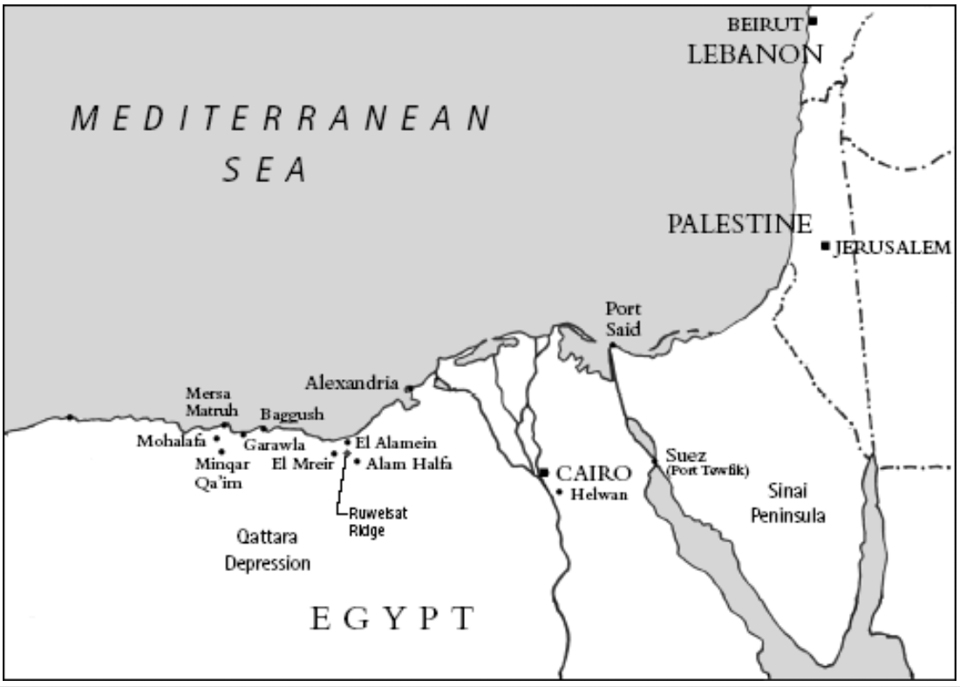

John enlisted into the army and served with the 1st Battalion, The King’s Royal Rifle Corps, being given service number was 4467736. The battalion was sent to North Africa early in the war to join the Eighth Army and from 1 February 1942 formed part of the 4th Light Armoured Brigade within the famous 7th Armoured Division – the Desert Rats. By July the Panzerarmee Afrika, composed of German and Italian infantry and mechanised units under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, had struck deep into Egypt and threatened British control of the vital Suez Canal. The British commander, General Auchinleck, had withdrawn the Eighth Army to within 50 miles of Alexandria to give the Allies a relatively short front to defend and secure flanks. It was here, in early July, that the Axis advance was finally halted in the First Battle of El Alamein.

Rommel dug in to allow his exhausted troops to regroup, while British counter-offensives were unsuccessful. Auchinleck called off offensive action to rebuild the army’s strength. In early August, Winston Churchill visited Cairo and replaced Auchinleck with General Sir Harold Alexander as the Commander-in-Chief if the Mediterranean theatre. Lieutenant-General William Gott was appointed to command the Eighth Army but killed before taking command when the transport plane he was travelling in was shot down, and thus Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery became Eighth Army commander.

After a period of reorganisation, the 1st KRRC rejoined the 4th Light Armoured Brigade on 4 August, which was sitting behind its own minefields that extended from Himeimat. They used the following weeks for intensive training, alongside building dummy positions, guns, and minefields.

Faced with overextended supply lines and a relative lack of reinforcements, and well aware of massive allied reinforcements in men and material on the way, Rommel decided to strike the Allies while their build-up was incomplete. What he did not know was that thanks to the work of Bletchley Park in cracking the Enigma code, Montgomery knew of his intentions and deliberately left a gap in the southern sector of the front, protected by a minefield, while deploying his armour ready to spring the trap. The job of the 1st KRRC and the rest of the 4th Light Armoured Brigade was to cover the minefields and inflict maximum casualties before withdrawing.

From the 27th the 1st KRRC were warned nightly to expect an attack, which duly began on the night of the 30th. Their War Diary for this night notes that “One of the valuable lessons learnt in the Alamein Line was the fact that the German tanks and infantry were much inferior to their counterparts of 1940-41, and the myth of their invincibility had been offloaded. All ranks were keyed up for the coming attack and each one was determined to make the enemy pay dearly for any advance”. At exactly midnight the jeep patrols operating 5 miles in advance of the lines gave warning of large enemy columns advancing in their direction, and the battalion was stood-to.

The enemy soon appeared, and in the darkness the battalion engaged them as best they could, while the RAF bombed with great accuracy, sometimes within 300 yards of battalion positions. However, by dawn the enemy could be seen streaming through a gap in the minefields and as expected they were forced to withdraw their position around Himeimat to Gaballa. The enemy did not follow, and instead swung away to the north. Not taking any chances, the positions at Gaballa were abandoned on the evening of the 1 September, “much to the disgust of the diggers”.

The 4th Light Armoured Brigade did its job. They harassed the German right flank and forced Rommel to turn northeast earlier than he had planned – right into the main defensive positions which brought the Germans to an abrupt halt. The Axis attack, better known as the Battle of Alam el Halfa, had failed. It was their last big offensive in North Africa. A few days later the 1st KRRC reclaimed their old positions near Himeimat

Expecting a counterattack by Montgomery’s Eighth Army, the Germans dug in. The factors that had favoured the Eighth Army’s defensive plan in the First Battle of El Alamein, the short front line and the secure flanks, now favoured the German defence. Rommel, furthermore, had plenty of time to prepare his defensive positions and lay extensive minefields (approximately 500,000 mines) and barbed wire. Alexander and Montgomery were determined to establish a superiority of forces sufficient not only to achieve a breakthrough but also to exploit it and destroy the Panzerarmee Afrika in North Africa for good. After six more weeks of building up its forces, the Eighth Army was ready to strike. 220,000 men and 1,100 tanks under Montgomery made their move against the 115,000 men and 559 tanks of the Germans at 9.40pm on 23 October 1942.

The battle began with a mass artillery barrage that was timed so that the rounds from all 882 guns would land across the entire 40-mile front at the same time. In the early hours of 24 October, British infantry and engineers began Operation Lightfoot, a painstaking and hazardous process of creating two channels in the minefields through which the armoured forces were to advance. The plan was for the infantry to attack first, since the soldiers would not trip the mines by running over them, and as they did so the engineers would clear a five-mile path for the tanks coming behind. The main force would attack to the north, while the 13 Corps, including the 7th Armoured Division and John’s 1st KRRC would make a feinting attack to the south near Himeimat ridge, aimed at pinning down the 21st Panzer Division and the Italian Ariete Division around Jebel Kalakh.

By 5am the 1st KRRC had advanced into no man’s land between the British and German minefields and began to suffer casualties from heavy shelling. However, they found that the expected paths through the minefields had still not been cleared. The minefields had proven thicker than anticipated, while the engineers were impeded by heavy defensive fire. Progress was slow and by the evening they had still not entered the second enemy minefield. It did not matter for John Frediani though, since he had been killed earlier that day.

Fighting continued until 5 November, during which the Eighth Army gained ground on a six-mile front. The Allied victory at the Second Battle of El-Alamein turned the tide in the North African Campaign, but it cost 13,500 allied casualties, including Rifleman John Frediani.

John was buried at ‘Alam el-Tritriya before being re-buried in plot 19.E.18 at the El-Alamein War Cemetery, Egypt, on 19 May 1943.

Units

- 1st Battalion, The King’s Royal Rifle Corps (1941-1942)

Medals