John enlisted into the army on 10 December 1915 when aged 17. He was described as 5 feet 6 inches tall, weighing 126 lbs and with a 34-inch chest. He was given service number 21452 (later 241824) and joined the 2/5th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. The 5th had originally been created in 1908 as a unit of the Territorial Force.

Since men in the Territorial Force could not be forced to serve overseas, the 5th were asked to volunteer to do so by signing the ‘Imperial Service Obligation’. Those that refused to do so were separated from the others and formed the basis of the 2/5th Battalion. John evidently refused.

The Military Services Act of January 1916 however, made all troops liable for overseas service and the 2/5th began training for deployment to France.

Easter Rising

On Easter Monday 1916, Irish nationalists launched an armed revolt against British rule in Ireland. The revolt came as something of a shock to the British. There were only a few troops in Dublin, so soldiers were rushed there from elsewhere in Ireland, and from across the sea in Britain. The 2/5th arrived on 25 April and engaged in fierce street fighting. John did not arrive until 21 May however, by which time the fighting was over. The Battalion moved to Fermoy in the south of Ireland, where John was hospitalised four times in quick succession at the end of the year for scabies. He was promoted to Lance Corporal in November.

The Western Front

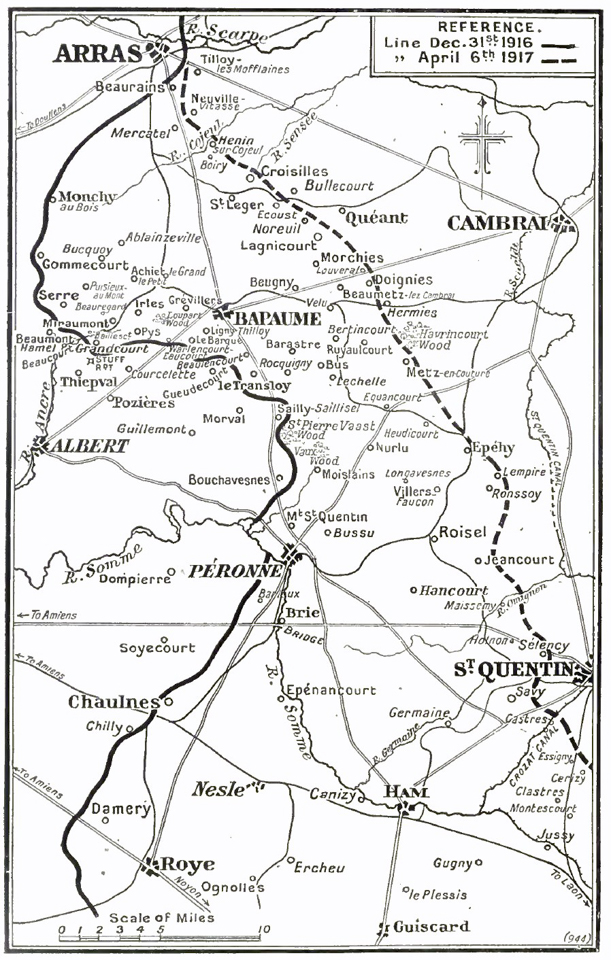

The 2/5th returned to England in January 1917 to rest and train at Harpenden near St Albans, before embarking for France the following month. After just a week or so of training the Battalion joined the line near Bayonvillers, to the east of the Amiens, on 7 March. The found the trenches in a bad condition, with men often having to be dug out of the mud. The mounted a few night-time patrols to gather intelligence, but other than that the week was a quiet one. They then returned to their camp behind the lines at ‘Triangle Wood’ where they spent the next week bathing, cleaning, training, and parading. They then spent a few days repairing a road, observing that the Germans appeared to have retreated a “considerable distance”.

The German retreat

Indeed they had, as this was the beginning of the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line which was undertaken between 14 March and 5 April. Carefully planned and executed it consisted of successive withdrawals to pre-planned temporary defensive lines utilising a predominantly machine gun defence. In addition, the Germans implemented a ‘scorched earth’ policy: villages were flattened, wells poisoned, rail lines destroyed, roads were mined, key bridges (especially those crossing the Somme), were thoroughly wrecked and every dugout and pill box was sown with booby-traps designed to catch out the unwary souvenir-hungry soldier.

The British response was slow. Some of the caution displayed was because they did not know if the German withdrawal was permanent or whether it was setting up some form of counterattack on the pursuing army, but mostly it was because after three years of trench warfare the British were simply not set up for mobile operations.

The 2/5th made its way east from 25 March, passing through Eterpigny and Beaumetz to Nobescourt Farm in a newly captured area, where they set about making a line of resistance. After about a week of work they were on the move again, pushing yet further east first to Roisel and then to Templeux and Hargicourt where they helped to capture German positions at Malakoff Farm on 10/11 April. They remained in position for the next week, suffering a few casualties to shelling and sniper fire, followed by a week of rest and training a few miles to the rear. This pattern continued until early July with quiet spells in various advanced positions followed by periods of rest, training, and working parties.

On 11 July the Battalion went for six weeks rest at Barastre, where the days were spent training on bayonet fighting, stretcher bearing, sniping and so on, alongside sports and games, and for a lucky few some leave in England. They then travelled to Hedauvile by bus, where they focussed on training for attacks on small fortified strongpoints in anticipation of the coming battles.

In late August they travelled by train to Winnezeele, arriving in Flanders on 1 September 1917 where training continued for much of the month. However, they were about to be engaged in their first full-scale action since arriving in France nine months ago.

Battle of the Menin Road Ridge

The Battle of the Menin Road Ridge was a general attack of the Third Battle of Ypres in an attempt to take sections of the Gheluvelt Plateau which the Menin Road crossed. It was the first time that a new ‘bite and hold’ strategy was used. Rather than trying to break through on a wide front, and eventually being halted by the deep German defence system, the attack was instead concentrated on a small part of the German front line. This would be heavily shelled and then attacked in strength. The advancing troops would stop once they had penetrated 1,500 yards into the German lines. At this point they would dig in, and another wave of attacking troops would pass through them to attack the next objective. The original attackers would then consolidate the ground they had taken and become the new reserve for future advances. It meant that when the German counterattack was inevitably launched, instead of finding a mass of exhausted and disorganised men at the limit of the Allied advance, they would find a well organised defensive line still in range of supporting artillery. The attack was successful, an although the advancing troops had to overcome formidable entrenched German defensive positions, they were able to resist fierce counterattacks.

Although the battle had begun on 20 September, the 2/5th was not involved until the 25th. The war diary records “the battalion attacked, gained, and held its objectives”. Over the next few days, they were subject to constant shelling, including a mustard gas attack, and in total the operation 17 killed, 195 wounded and 74 missing.

They withdrew on 1 October and then over the next two weeks made their way back south to the Lens area, but this time covering the 40 miles mostly on foot. They then had uneventful periods in and out of the line around Lens until the middle of November. The end of the month involved another 40-mile march – to Flesquieres, near Cambrai – where they supported the engineers in digging defensive trenches and dugouts, bookend by spells on the line where they suffered intermittent shelling, gas attack and strafing from enemy aircraft.

Desertion and court martial

On Christmas Day the Battalion travelled to Tinques by train – about 45 miles to the northwest – from where they marched to Ambrines. The next six weeks were spent resting and training ahead of the next anticipated push. Between 9-12 February they marched to Bullecourt to take over a section of the line. John went missing on this journey. The official report states:

Whilst on active service, he deserted H.M. service in that he in the field on 12 February 1918, though fit for duty, fell out from his battalion on the way to the trenches and did not re-join his company when ordered to do so, but remained absent until report to the transport on 15 February 1918.

This was a very serious offence, and John was arrested and charged with desertion, a crime punishable by death. He was imprisoned for 71 days whilst waiting trial, facing a General Court Martial in the field on 26 April. Thankfully for him the court returned a verdict of not guilty of desertion but did find him guilty of being absent without leave. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labour, although when the report of the court was submitted to the relevant authority, the confirming officer reduced the sentence to 90 days imprisonment. With time already served taken into account, John was soon released, and no doubt a relieved man.

A new battalion

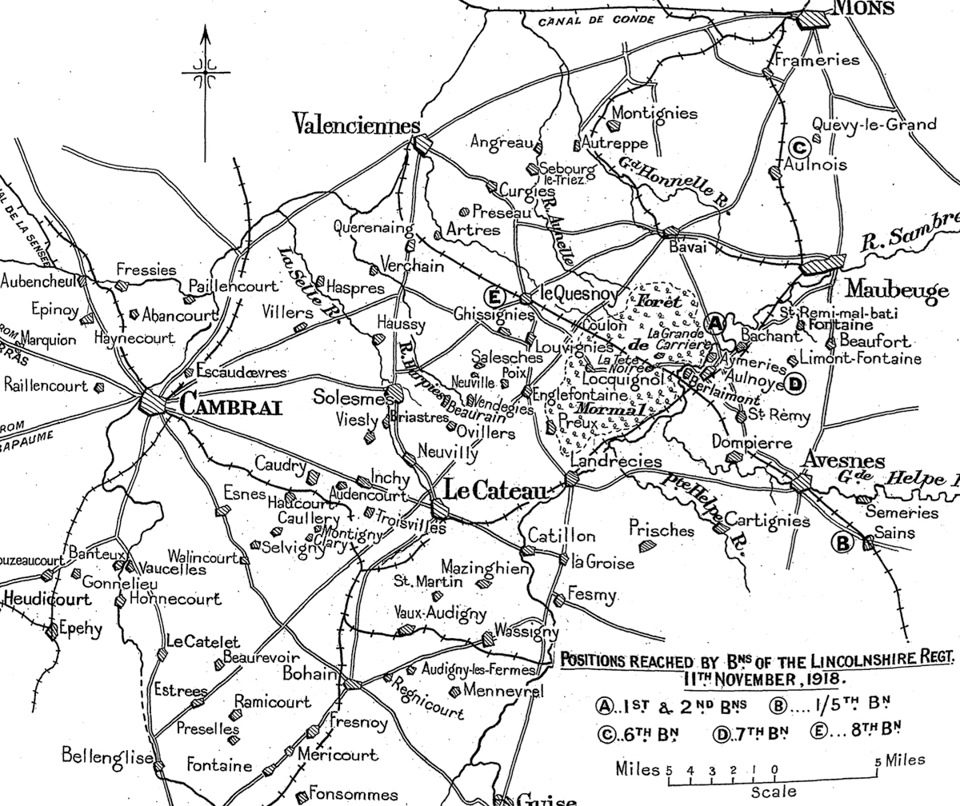

John did not re-join his original unit, which had suffered heavily in the Battles of Bapaume and Bailleul in March and April and were subsequently reduced to a training cadre establishment. He was instead transferred to the 7th (Service) Battalion of the same regiment, part of the 17th Division, arriving at the end of July 1918.

John found his new Battalion in Martinsart near Albert on the Somme. The war was about to enter its final phase with a series of Allied drives known as the Hundred Days Offensive. Four years of stalemate and trench warfare was over.

Battle of Amiens

The Battle of Amiens began on 8 August 1918 with Allied forces advancing over 7 miles on the first day, one of the greatest advances of the war. Although not directly involved in the attack, the 7th relieved the Australian troops holding the line at Proyart on the night of the 12 /13 August, and over the next week suffered heavily casualties. After being relieved they marched to take up assembly positions east of Thiepval for the next attack. At 10.30 pm on 24 August they advanced due east towards Courcelette. Although at times held up by machine-gun fire, and twice counter-attacked by the enemy, which were easily repulsed, they continued the advance until relieved on 30 August. They had suffered 211 casualties.

After a few days rest the 7th were once again pushed forwards, their objective being the sunken road north of Equancourt. The position was gained on 5 September, but with 115 casualties. They spent the next two weeks in reserve, before being readied to participate in their next action.

Battle of Épehy

The Allies and now reached the Hindenburg Line – an impregnable series of fortified redoubts, machine gun positions and fields of thick wire entanglements, 10 miles deep and 40 miles wide from Cambrai to Le Fère. It would need to be breached. Part of the plan were a series of attacks to clear German outpost positions on the high ground. The objective was a fortified zone near Épehy, roughly 3 miles deep and 20 miles long, supported by subsidiary trenches and strong points. On 18 September at 5.20am, the attack opened and the troops advanced. The 7th advanced in the area of Villers-Guislain, and after passing through an initial German gas bombardment met heavy machine gun resistance. This was superbly countered by a Captain Parsloe who worked around the enemy and hit them from the side, capturing some 200 prisoners. After this the Battalion advanced steadily and gained all of their objectives before being relieved the following evening but suffered 22 killed and 240 wounded in 36 hours.

The final battles

They were withdrawn and spent the next few weeks resting, training, and receiving replacement men. They moved forward on 8 October in preparation for their next attack.

For the first time the advance lay through open country which the Germans had held since 1914. Towns and villages showed no trace of shellfire, there were fields without craters, and woods not reduced to mere branchless stumps of trees. The 7th’s participation in the Battle of Cambrai was somewhat sedate, as they advanced unopposed over the open country north of Walincourt.

The retreating Germans had taken up a new position immediately to the east of the Selle River. The Fourth Army attacked on the night of 17 October with infantry and tanks moving forward on a 10-mile front south of Le Cateau. The 7th Lincolns entered the action on the 20th, and in a day of hard fighting lost seven killed and 93 wounded. They were once again withdrawn into the reserve.

German resistance was falling away, and it was vital to keep up the momentum before winter could set in. A new attack was quickly prepared to advance along a 30-mile front. The last great concerted movement of the war, the attack was launched at 6.15am on 4 November. In rain and absolute darkness, the 7th Lincolns set out from Poix du Nord at 7.30pm the evening before to reach their assembly positions. Despite rain, cold and hostile shellfire, the men snatched a little sleep and at zero hour advanced through a heavy mist that obscured everything. When the fog eventually lifted, they moved through a forest with little resistance and continued to advance for the next few days. After this they held position in anticipation of the Armistice.

The Armistice was signed on 11 November, after which the men were billeted. The bulk of the army remained in position until March 1919 when it could be certain that the Germans had withdrawn back behind their own borders. This time was filled with a mix of training, sports, work parties, parades, boredom, and social events. John did not return to England until 1 September 1919, being formally demobilised on 30 September 1919.

Units

- 2/5th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment (1915-1918)

- 7th (Service) Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment (1918-1919)

Medals