Robert enlisted into the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force almost immediately after the outbreak of war in 1914, signing-up at Kamloops, British Columbia on 12 August and attesting at Valcartier, Quebec a week later. He stated that he had served for four years previously with the King’s Liverpool Regiment. At 24, he stood 6 feet 1 inch tall, with a 38-inch chest, weighing 165 pounds, and had a fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. He had a scar over his right eye from a fall in childhood and small moles on his forearms.

News of his enlistment was featured in the Flintshire Observer on 24 September 1914:

Robert joined the 5th Canadian Infantry Battalion with service number 13418. After training at Valcartier, the Battalion embarked on the SS Lapland at Quebec and sailed in a convoy of 30 transports with naval escort from Gaspe on 3 October, arriving at Plymouth two weeks later. The winter of 1914/15 was spent training on Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, where the Canadian Division (later the 1st Canadian Division) was organised. Towards the end of this training on 4 February, the Battalion was inspected by HM King George V and Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War. Robert was promoted to Corporal two days later.

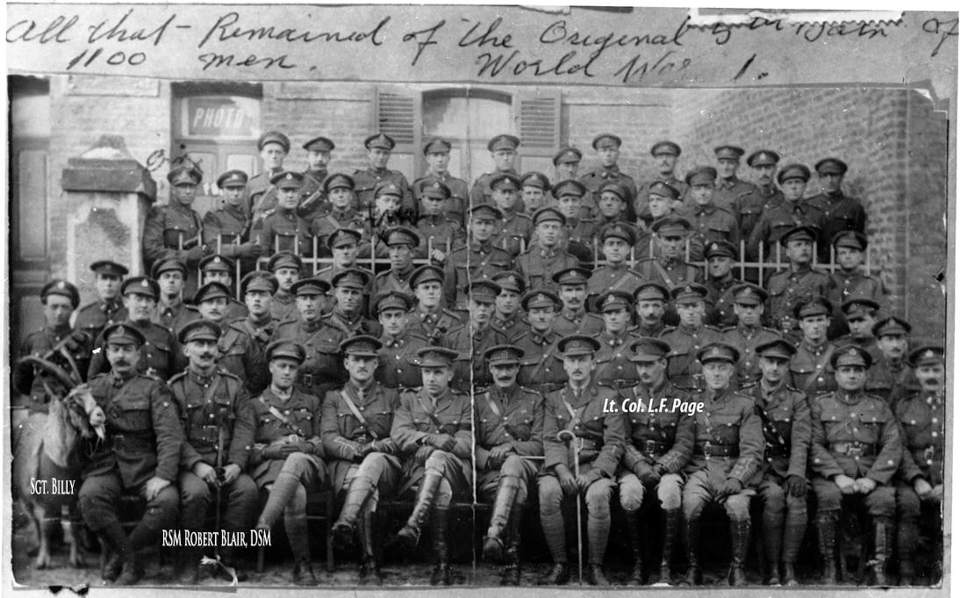

The Battalion embarked on the SS Lake Michigan at Avonmouth for the voyage to St Nazaire, France. From then until the Armistice in 1918, the Battalion saw prolonged and arduous service which cost them 1,297 killed and 3,221 wounded.

Family’s Good Response: Alderman and Mrs J.W.M. Evans, Pendre, have both sons and three nephews who have responded to the call "Your Country Needs You." Mr G. Neville Evans has joined the Yeomanry at Birkenhead; Mr Arthur Leslie Evans, the Corn Trade "Pals" Battalion, and is now at Prescot; Lieut. Sydney Evans is with the 2nd Liverpool Rifles at Dunfermline; Mr Frank Pierce, Insurance "Pals" Battalion, Prescot; and Mr Gerald Foulkes is coming from Canada with the Colonials.

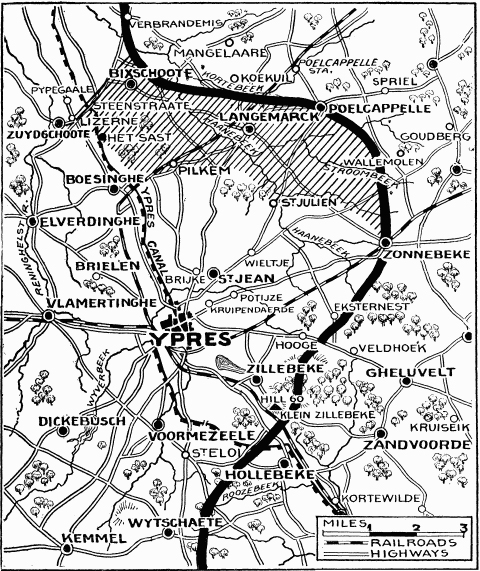

The Battles of Gravenstafel Ridge and St. Julien

They initially made their way to Merris, where after being inspected by General John French, the Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, they proceeded to Armentières. They went into the trenches for the first time in early March for their first two-week spell on the line. The front was relatively quiet, with a few men killed and wounded by snipers and occasional shelling. After a week of rest in billets, they moved back into the trenches once more. The first half of April was spent in reserve before they moved into the trenches at Gravenstafel, northeast of strategically important Ypres on the 19th.

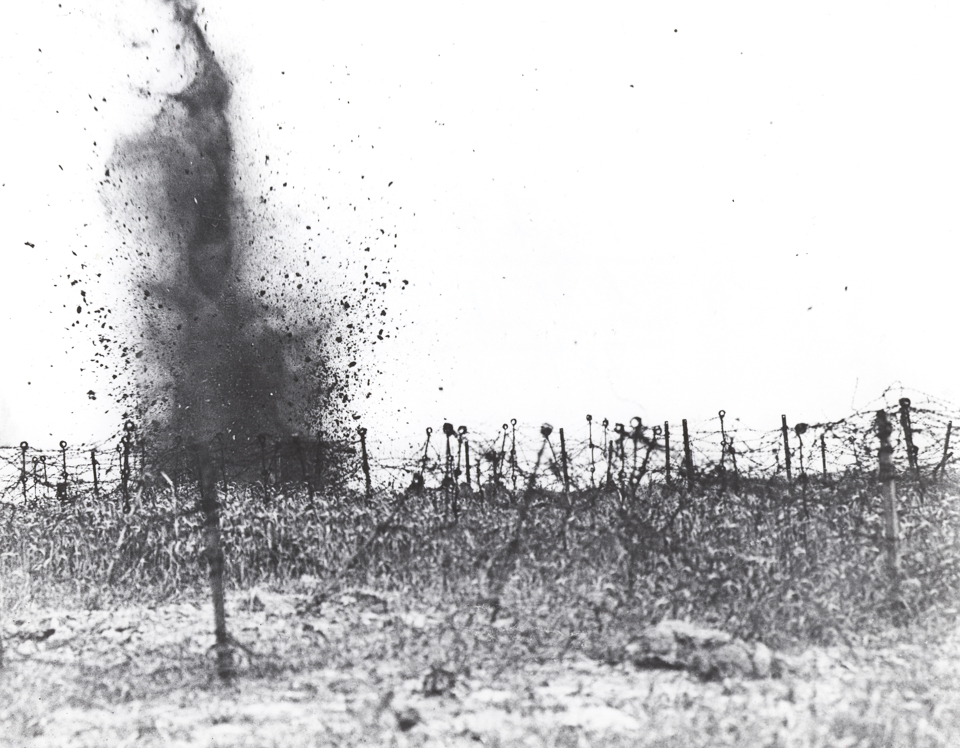

This was a much hotter section of the line, and they immediately came under heavy daily bombardments that caused several casualties. On the 22 April at about 5pm, the Germans launched its first gas attack of the war – directed to the left of the Canadian portion of the front line, where French colonial troops and British artillery held the sector. With the use of gas unexpected and without any protection against it, they suffered 2,000–3,000 casualties and as they fell back left a 4-mile gap in the line that was quickly occupied by the Germans. More gas followed the next day, and although not directed at the 5th Battalion, they nevertheless suffered with the men “complaining of gas, sore throats and eyes prevalent”.

The Germans launched a second attack on the 24th, beginning with another gas attack on the neighbouring 8th Canadian Battalion and followed by infantry, forcing the 5th to send reinforcements to plug the gaps. The war diary noted that “about 1pm some of the 8th Battalion steamed past, having thrown their rifles away”. They were stopped and ordered back into line, but a general order for the 5th and the 8th to retire was given at 4pm. The 8th withdrew quicker than expected leaving the 5th alone in the trenches, and so their commanding officer “personally went down to the road and brought back some 300 men”. The 5th then withdrew under very heavy machine gun and shrapnel fire, with only the cover of darkness preventing a catastrophe. The remains of the Battalion assembled on the morning of the 26th at St Jean but were shelled heavily and suffered severely. It was during this action, either in the withdrawal or the subsequent shelling, that Robert was shot in the chest. The Battalion lost over 235 men killed and wounded in just a few days.

Recovery in England

Robert was initially sent to the 12th General Hospital at Rouen before sailing for No.5 Southern General Hospital at Portsmouth during May. He was sent to Longleat Convalescent Hospital in Wiltshire after a few days. This had been one of the first stately homes to answer the country’s call to provide space for the nursing of war casualties. During his four-month stay, Robert recovered in comfortable surroundings and even enjoyed a full programme of entertainments. At the end of September, he was passed to the new Canadian Convalescent Hospital in Woodcote Park in Epsom. The patients, who wore the saxe blue uniform of the convalescent soldier, had been discharged from acute hospitals and stayed for up to six weeks until they were well enough to return to their fighting units. During their time in convalescence, they received physiotherapy from masseuses, while a staff of trained Sergeant-Instructors provided physical training and the discipline of graduated route marches. All sports were encouraged to get them back into fit condition, and the patients regularly played baseball (previously unknown in England), as well as cricket and football against the local teams. Every evening entertainments, whether home-made or from London, were provided in the Recreation Hall (which could hold an audience of 1,500) – a theatrical performance, a film show, a concert, or a lecture. If fit enough, many patients were allowed to visit Epsom.

After just a week Robert moved on to the Central Military Hospital in Shorncliffe, where he was discharged to undertake light duties. He first joined the co-located 32nd Reserve Battalion, and then on to a training school of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) in November and to the 3rd Canadian Casualty Clearing Station in December. He remained here until leaving for France on 24 March 1916, almost a full year after being wounded.

Return to the front and a quiet summer

Robert re-joined the 5th Battalion on 7 April 1916, finding them not far from where he had left them – in billets around the town of Poperinge. They went into the trenches around Hill 60 on the 17th and had a fairly quiet time of it until the 24th when they suffered a heavy bombardment that killed or wounded 68 men. The war diary records that “whole trenches were completely blown in and when the bombardment eased our men were just holding small holes here and there. The moral of the men was excellent throughout it all.” They were withdrawn to billets the following day. On the 28th they were inspected by General Sir Douglas Haig, the British Commander-in-Chief. Two days later there was a memorial for the men killed in the Second Battle of Ypres a year before, in which Robert had been injured.

Robert was promoted to Sergeant on 5 May. They went back into the trenches on the 11th and had a relatively quiet week, returning again on the 30th where they suffered more heavy bombardments with 146 killed and wounded during their six-day stint. For the remainder of the month they were held in reserve, spending their time on working parties and helping to carry to the dead and wounded.

The Battalion went back into the trenches on 1 July 1916 – the infamous first day of the Battle of the Somme, taking place 80 miles to the south, in which 57,470 men were killed or wounded. Their week on the line passed quietly and they withdrew into reserve again. This pattern repeated twice more until on 13 August they began to make their way to Hellebrouck in the rear for an extended period of training, including attack practice, rifle exercises, bayonet fighting, and physical drills. At the end of the month, they moved towards the battlefields of the Somme.

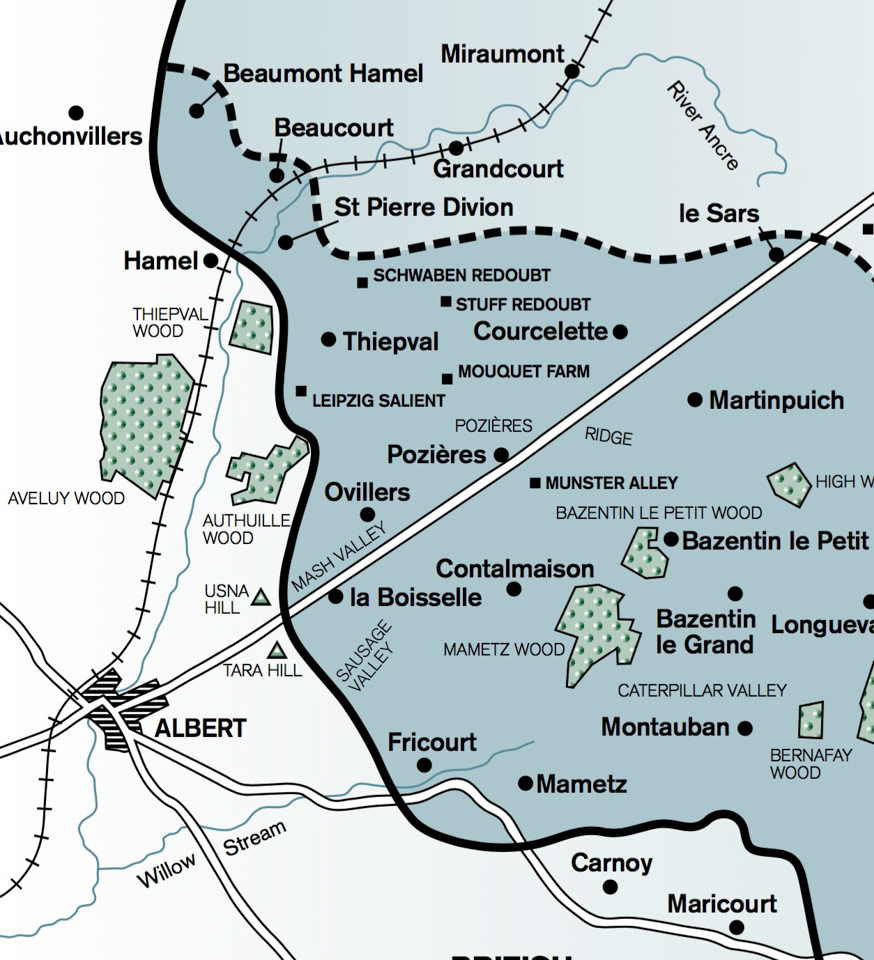

The Somme Offensive

The Battalion went into the trenches around Albert on 10 September 1916 for a brief two-day re-familiarisation. After another two weeks of training, they entered the lines proper on the 25th with orders to attack the next day. The war diary records: “Everyone is keyed up, for it is what many have put in 18 months waiting for”. This is surely putting a positive spin on events. It is rather unbelievable that given the slaughter that had taken place on the battlefield in front of them over the past three months – 600,000 killed or wounded – that anyone would feel anything other than fear about going over the top.

The plan was to push the Germans off the well-fortified high ground between the villages of Thiepval and Courcelette. The front was divided in two: the left half to be attacked by the British II Corps and the right by the Canadian Corps. According to the plan, the Canadians had to capture a succession of German trenches along the ridge (named Zollern, Hessian and Regina). The attack was launched at 12.35 on the 26 September, with the men scrambling up over the trench behind a brief but intense artillery barrage. The first trench (Zollern), some 300 yards away, was quickly captured with some prisoners taken. The first wave had been “thinned out” in the attack, but they united with the second wave to launch an attack on the next objective. The war diary picks up the story: “As the barrage was moving very slowly the men would advance a short distance and then lie down and wait till it again lifted. The casualties between the first and second objectives were very heavy and the number of men who reached the Hessian Trench were few indeed.” Nevertheless, those that survived set about consolidating their position and meeting up with neighbouring battalions, holding the enemy trench until relieved the following afternoon. The operation had cost the 5th 492 men killed, wounded, and missing in what became known as the Battle of Thiepval Ridge. Fighting continued for the next few days during which the Regina Trench was also captured.

The was little rest for the depleted Battalion, who made several daily working parties in and around the trenches. They finally moved to the rear on 17 October and spent the next few weeks training the replacements who had joined. They moved back into the line on 6 November, but quiet had once again returned and their two-week spell was uneventful. Another stint in December was equally uneventful. The Battalion finished the year resting at Houdain – to the north of Arras – with the time spent in a mixture of physical drill, lectures, and sports.

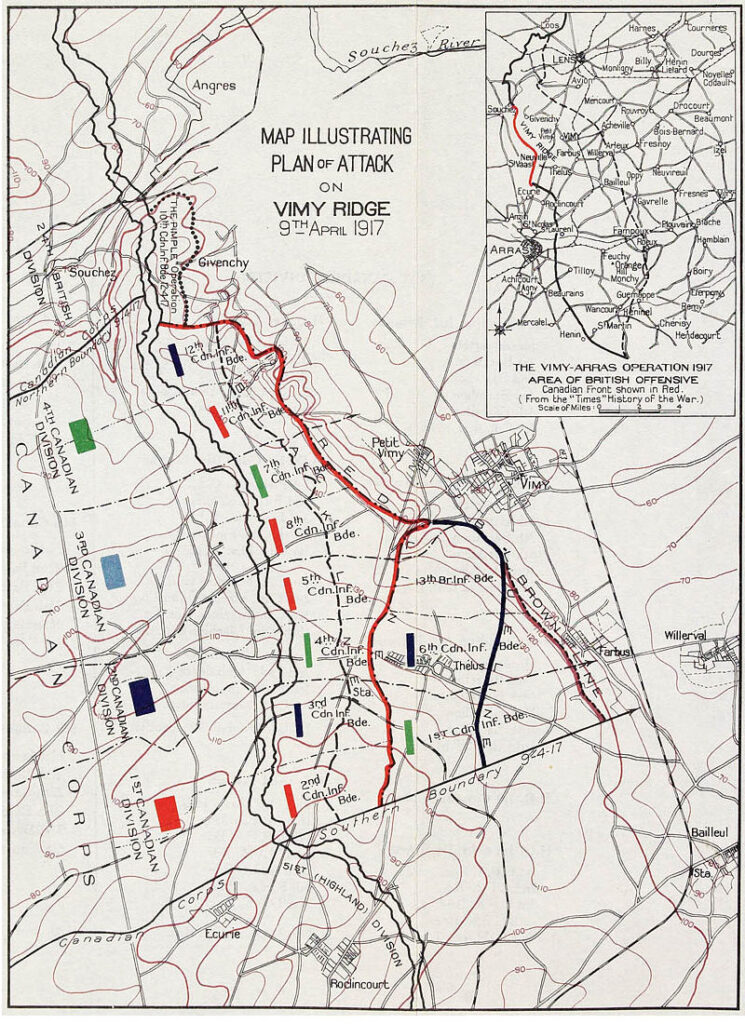

Battlefield commission and the Battle for Vimy Ridge

Having entered the army as a Private, Robert was given a temporary battlefield commission to Lieutenant on 7 January 1917, receiving a certificate from HM King George V. The Battalion went back into the line near Angres on the 24th, but it was at around this time that Robert returned home for 10 days leave in England. No sooner had he returned than he was dispatched to attend a week-long grenade course at the Divisional School – re-joining his Battalion back in the trenches. The remainder of February and all of March were spent alternating between quiet spells in the line and working parties out of it, alongside training for the next big attack. The Battalion spent periods at Fosse, Écoivres, and Cambligneul before entering the line on 5 April.

The British attack in Arras opened the Allied offensive in 1917. The Canadian Corps was charged with taking Vimy Ridge to safeguard the left flank of the main advance. The heavily fortified four-mile ridge held a commanding view over the Allied lines. In previous years the French had suffered 150,000 casualties in various attempts to gain control of it and the surrounding territory. For the previous two weeks the German positions had been subjected to a systematic bombardment that almost completely demolished defensive works and affected the health and morale of the defending troops.

The attack began at 5:30am on 9 April – Easter Monday – in cold weather that later changed to sleet and snow. The men climbed up from their positions and began to advance under a creeping barrage. The plan divided the Canadian advance into four coloured objective lines, with units leapfrogging over one another to maintain momentum.

The 5th Battalion formed part of the initial wave and quickly overran the German frontline, with the men “using the bayonet to good effect” to clear what little opposition there was. They then pushed on to the Black Line objective but suffered heavy causalities from machine gun fire with many officers and sergeants killed. Once the guns had been dealt with then Black Line was consolidated and they very quickly gained the Red Line too. There they rested and waited for the reserve units to move up, while enjoying the “almost luxurious conditions” of the German dug outs including electric lighting and hot coffee, while the wounded were evacuated. For the next few days, the Battalion moved in reserve to other units as they achieved their objectives, and by the 12th the Canadians had firm control of the ridge – and indeed it remained in Allied hands until the end of the war. It was a stunning success, but at a cost to the Battalion of 365 men killed and wounded.

Winning the Military Cross at the Battle of Arleux

The Battalion did not have long to rest for another attack was launched on 28 April. The Arleux Loop was a part of an intricate system of German defences that were intermingled with the village of Arleux-en-Gohelle, heavily fortified with concrete, extensive belts of wire and what patrols reported as an “unusually large amount of machine guns”.

This attack was part of a British effort to push the German line back to aid the French attack at the Aisne. The attacking force consisted of three Canadian battalions, with the 5th on the left of the attack. At 4:25 am, they stormed towards the German front line. It was soon found that the artillery barrage had failed to cut the wire on the left side of the attack. There was only one route through the wire, which was well covered by machine gun fire and began to take a heavy toll on the attackers. By this time the support company had caught up and “seeing the difficulty that D Company was having in gaining their first objective on account of the wire, a party under Lieut. Foulkes entered the trench on C Company’s frontage, and bombed up to the left, soon clearing the trench of all Germans.”

After that the rest of the attack progressed smoothly – although the Battalion had lost another 250 killed and wounded. Robert was later awarded the Military Cross for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in leading a bombing party across the open into an enemy trench, which he cleared of the enemy, enabling his platoon to continue its advance”.

Third Battle of Ypres and Hill 70

May and June were spent either training and parading, or in reserve, in which case they undertook work parties in the rear areas. Robert attended the Canadian Corps School for most of May. On the 3 July he was placed in command of a group of seven lucky men who were chosen to spend the next two weeks in a rest camp at Boulogne. They returned to find the Battalion halfway through a spell in the trenches – but they were soon withdrawn and spent the rest of the month in reserve again. They moved to Braquemont at the start of August and went into the line near Loos on the 13th and prepared to attack the next day.

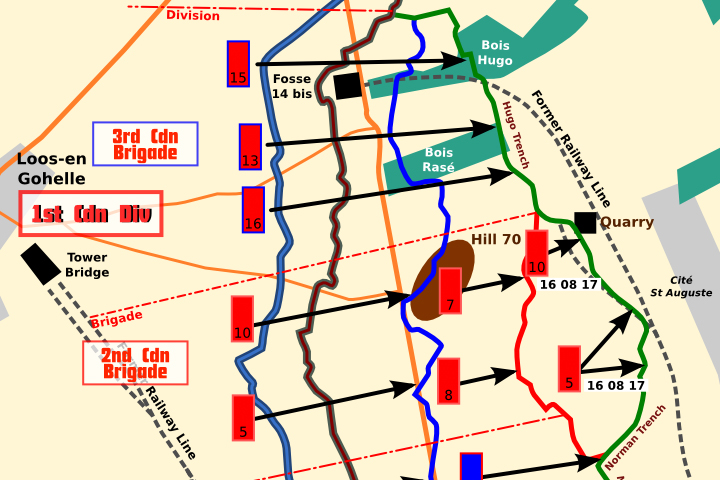

The Canadian Corps were ordered to capture the city of Lens to draw German troops away from the ongoing Third Battle of Ypres. They planned to quickly take the high feature of Hill 70 that dominated Lens from the north, and then establish defensive positions to repel German counterattacks and inflict as many casualties as possible.

The first objective was the German front-line, the second objective (Blue Line) was the German second position on the crest of the hill and the third objective (Green Line) was the German third line on the far slope. At 4:25am the creeping barrage began and the infantry advanced. C and D companies captured the German front-line with very little opposition. As planned, A and B companies – with the former commanded by Robert – passed through and immediately attacked the Blue Line, suffering many casualties to machine gun fire before reaching their objective. They succeeded in capturing the position, with A company capturing 30 prisoners. They immediately came under German bombardment as they consolidated their position. During the night the Germans counterattacked several times, but each time were driven off.

At 4pm the next day the assault on the Green Line was made, and after some “very stiff” fighting the objective was taken – but the Germans counterattacked repeatedly. At about 5.30pm A company was withdrawn as it now numbered just six men and had run out of ammunition. Robert was extremely lucky to survive. That night the Battalion was relieved and moved back to Les Brebis. They had lost 365 men over the two days. The German counterattacks continued for the following days with little success and operations came to an end on 25 August. The Canadians had failed to take Lens, but Hill 70 remained in Allied hands until the end of the war.

For this part in this action Robert received a Bar to his Military Cross (a second award) for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. After capturing his objective, he again went forward and personally led a bombing attack, which resulted in the capture of the second line. He and his party held this line against three counterattacks, accounting for many of the enemy, until at last their ammunition ran out and they were forced to retire. He then manned a machine-gun and covered the retirement of his men, refusing to leave until all were clear. Throughout the operation his gallantry and personal example were most inspiring to his men.”

Passchendaele

Robert left for 10 days leave in England immediately after the battle. The next six weeks consisted of work parties between short spells manning the lines, and although there were frequent bombardments and gas attacks, the casualties were few. On 19 October they left the area to move north to Thiennes where for the next month they trained for the next big attack. On 7 November they moved to Ypres to re-enter the Third Battle of Ypres and went into the line near Meetcheele two days later.

For the past three months the Allies had been fighting a bloody battle for control of the ridges south and east of Ypres. A series of smaller battles had pushed the Germans back to the last ridge east of Ypres: Passchendaele. In mid-October, with the battle bogging down due to British and Australian exhaustion, the stubborn German defence and the bad weather, the Allies sent for the Canadians to make a final push and try to salvage a victory. Other Canadian units began the offensive on 26 October, and it was not until 9 November that the 5th Battalion was committed – operating as brigade reserve to the 7th and 8th Battalions spearheading the attack. Despite this, while waiting in reserve, they suffered very heavy casualties from accurate German shellfire. The Battalion was committed on the 10th and fought throughout the day. Passchendaele ridge was captured, but the 5th lost another 320 men killed and wounded.

Return to England

The Battalion then returned to the familiar routine of alternating between manning the front line and being held in reserve in billets, spending their time on work parties. Robert was also able to spend Christmas 1917 at home. He was promoted to Captain upon returning to his unit on 29 December and appointed the Officer Commanding A Company. A month later however he was transferred to the 15th Reserve Battalion for instructional duty, spending most of the remainder of the war in England at the Saskatchewan Regimental Depot at Bramshott.

Robert returned to France once again during October, re-joining the 5th Battalion at Estrées, about 15 miles east of Arras, on the 16th. The war was by now a mobile one, with trench warfare left behind as the Allies chased the retreating Germans. The Battalion was being held in reserve however and spent the rest of the war at Masny. The war diary entry for 11 November records:

In the evening we received the great news that the armistice had been signed, and that hostilities had ceased. Today is indeed an history day, and we read with a shudder our position twelve months ago when we were immersed in the mud of Passchendaele. A double issue of rum materially added to our satisfaction, and rounded off what was described by the men as a perfect day.

After a brief period in the Rhine area to the east of Cologne, the Battalion settled in Warnant in southern Belgium while it awaited its return to Canada. Robert sailed for England in March 1919 and then on to Canada onboard the SS Carmania in April. He was immediately demobilised at Regina, being one of the lucky few to serve the entire war and survive. His health upon demobilisation was reported as being very good.

Service in the Second World War

In the 1920s period Robert married and emigrated to New Zealand with his new bride, where they settled in Wellington. After the outbreak of war in the Pacific in 1941, Robert joined the New Zealand Army and was commissioned as a Lieutenant (service number 824054). He was attached to the Branch of the Director of Mobilization at Army Headquarters in Wellington on 27 September 1941. By the end of the war, he had been promoted to Major.

Units

- 5th Canadian Infantry Battalion (1914-1915, 1916-1918), Canadian Army

- 15th Reserve Battalion (1918), Canadian Army

- Director of Mobilization at Army Headquarters (1941-1945), New Zealand Army

Medals