Following the outbreak of war in 1939, Bill left his job as a crane hand and joined the British Army, being posted to the 5th Field Regiment of the Royal Artillery with service number 3772016, which in 1941 was serving in India. They were dispatched to Singapore in November 1941 to reinforce the defences there.

On 8 December 1941 the Japanese began simultaneous attacks on the Far East territories of Britain, The Netherlands, and the United States. The Japanese 25th Army invaded northern Malaya and Thailand from Indochina, while strikes were also made against the United States naval fleet at Pearl Harbor. The plan was then to move south to secure Singapore, and then on to the oil-rich area of Borneo and Java in the Dutch East Indies. Other forces would land in the Philippines, and capture Guam, Wake Island, and the Gilbert Islands. Compared to the British Indian Army that defended Malaya, the Japanese were superior in close air support, armour, coordination, tactics, and experience. They easily passed through the ‘impenetrable’ jungle to outflank hastily established defensive lines and quickly gained air supremacy against obsolete Allied aircraft. Inflicting heavy casualties, they overran cities and advanced towards strategically critical Singapore, the Allied headquarters and gateway to the shipping channel between the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. The British rear-guard crossed into Singapore on 31 January 1942 and destroyed the causeway connecting it to the mainland.

Despite its importance, and general perception of it as an ‘impregnable fortress’, the defenders of Singapore were undermanned and badly equipped. Some reinforcements had been rushed to the area but given that the British were already stretched in North Africa, and the distances involved, these were limited. Although there were almost 85,000 troops, most were either exhausted from weeks of fighting, new raw recruits, or from second-line administrative units – all under the command of hesitant and defeatist commanders. Japanese shelling and air attacks intensified from the 4 February, severely disrupting communications, and affecting preparations for the defence. The invasion began on the evening of the 8 February, and despite brave resistance the defenders were overwhelmed. By 13 February they had been pushed back to form a 3-mile defensive perimeter around the city of Singapore itself, which still contained over a million civilians. The next day the Japanese breached the defences and massacred the staff and patients of a hospital. By now water, rations, petrol, and other supplies were almost exhausted. The commanders faced a choice of counterattack or surrender – they chose to surrender, and Singapore fell on Sunday, 15 February 1942. Bill thus entered a life of captivity.

Building the Japanese Death Railway

The Japanese completed their conquest of Burma three months later and then began to transfer large numbers of Allied prisoners to camps in Siam and Burma to commence building the infamous death railway to improve communications with the large Japanese army poised to strike at India. They aimed at completing the 258-mile railway through impassable terrain and an inhospitable climate in just 14 months. Work began in October 1942. Rather than start building at two ends and meet in the middle, as per normal railway construction, the Japanese created hundreds of camps across its lengths. ll but a small section of the route was built in dense, malarial jungles, in sweltering heat and monsoon rains. Some sections, such as the infamous Hellfire Pass, required carving through tough sheer rock.

In May 1943, the 7,000 strong ‘F’ Force, a mixed Australian-British labour force including Bill Bennett, was given the job of constructing a stretch of about 10-mile of line. The 1,600 British prisoners destined for the Songkurai No.2 Camp arrived there on 24 May 1943 after a gruelling journey. The first stage was undertaken in metal goods wagons, 35 men per truck through Malaya’s beating, relentless sun for five days and nights to Thailand. They then marched 220 miles through the jungles over 17 nights. Most of the prisoners were in bad shape, suffering from malaria, dysentery, diarrhoea, and general ill health due to fatigue and lack of proper food. The wet season had begun, it was cold, and the rain fell in torrents. The men who arrived were totally exhausted, and of these 1,600 only 250 would survive to liberation two years later. To reach the camp they had to cross the Huai Ro Khi river upon a very fragile wooden bridge. The clearing of the camp was covered in a thick carpet of black mud. The huts were 100m long and 6m wide, constructed of bamboo but lacking roofs or floors. The sleeping platforms were raised off the mud by bamboo slats.

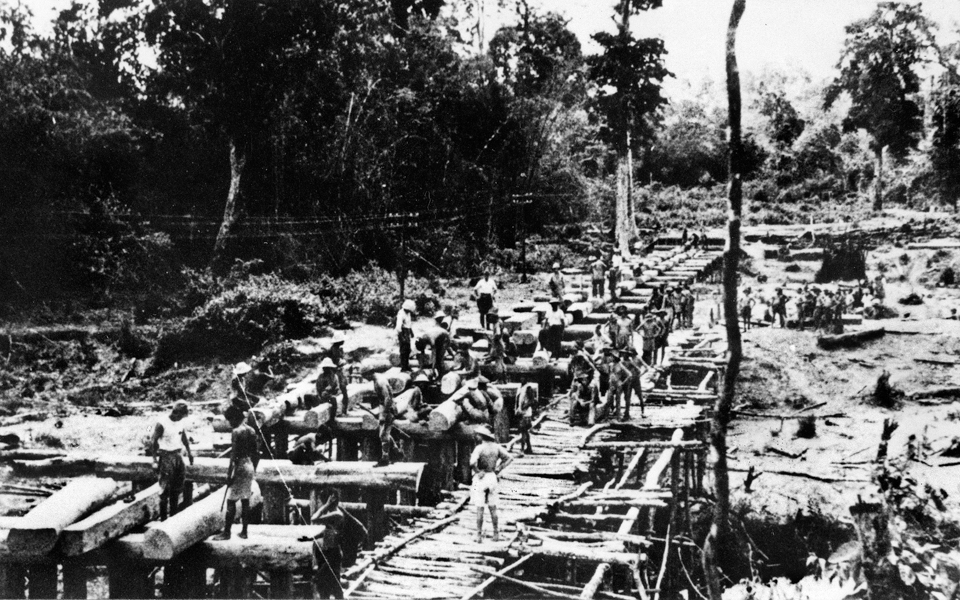

Work began almost immediately. Their task was to complete a 10-mile stretch of line within 5 months, including a wooden bridge over the Songkalia River (Huai Ro Khi). This is often confused with the bridge crossing the Mae Klong River (known locally as the Khwae Noi River) and later immortalised in the 1957 film ‘The Bridge Over the River Kwai’. This area was the most isolated of western Siam, near its border with Burma. The bridge was built entirely with timber and no mechanical devices were used. Work began at 5am and finished at 9pm. Blasting of the rocky hills could cause serious injuries, while those working all day in the cold river up to their chests risked slipping and being swept away in the rushing waters. Hundreds died, drowned, exhausted, beaten to death by the Japanese Engineers, who were by far the worst on the railway.

Within a week of arriving, cholera broke out in the camp and spread like a bushfire. There was no medical care, and at its height 35 men died each day until it abated in mid-June with about 600 men dead. Sadly, this included Bill who died on 31 May. All the corpses were cremated over a large open fire outside the camp, and their ashes were buried in a communal grave. His remains were exhumed and reburied in December 1945 at Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery in Burma. The village of Thanbyuzayat is 40 miles south of the port of Moulmein, and the war cemetery lies at the foot of the hills which separate the Union of Myanmar from Thailand. He left his estate of £133 13s 6d (around £4,700 today) to his mother.

The 263-mile-long line was completed by December 1943, by which time some 13,000 prisoners and 80-100,000 civilians had died. This is an abridged version of the excellent Roll of Honour website. Visit for much more detail.

In an interesting footnote, his POW record cites his year of birth as 1918, rather than the actual 1921.

Units

- 5th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (1941-1943)

Medals