Many of my ancestors worked in the iron and steel industry, both in the foundries of the great ironopolis of Middlesbrough, and in the steelworks along the North Wales coast where four generations of one family worked successively in the same foundry.

The Industrial Revolution led to a dramatic transformation in the production of iron and steel, moving from small-scale, labour-intensive methods to large-scale, mechanised processes.

The age of iron

Prior to the 19th century, iron production relied on a process called blast furnace smelting. This involved heating iron ore with charcoal in a furnace to separate the metal from impurities. While effective, it was slow and labour-intensive, restricting iron output. The resulting iron still contained impurities like carbon, making it brittle and unsuitable for many applications.

Process revolutions

A breakthrough came with the invention of the Bessemer converter in the 1850s by Henry Bessemer. This revolutionary process involved blowing air through molten iron to remove excess carbon as slag. This not only produced a higher quality steel but also did so in a faster and more efficient manner. Key features of the Bessemer converter included:

- Converter vessel: a large, egg-shaped vessel lined with firebricks capable of withstanding immense heat.

- Air blast: compressed air was forced through the molten iron, causing impurities like carbon to burn off as carbon monoxide gas.

While the Bessemer process was a major leap forward, it had limitations. It struggled to handle certain types of iron ore and could be difficult to control, leading to inconsistent steel quality. The Siemens-Martin open-hearth furnace, developed in the 1860s, addressed these issues. It offered greater control over the steelmaking process and could handle a wider variety of iron ore, resulting in higher quality steel with specific properties for diverse applications.

The age of mechanisation

Alongside these advancements in steelmaking processes, the 19th and early 20th centuries saw a surge in mechanisation within the industry. Tools and machinery played a crucial role in production, leading to more uniform products that met higher standards of performance and reliability:

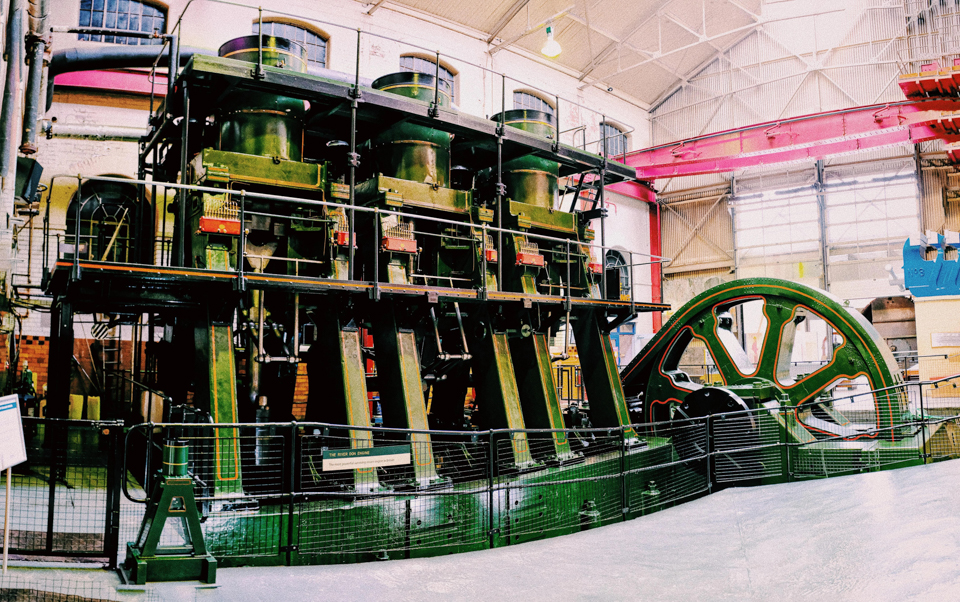

- Blast furnaces, which were crucial for smelting iron ore into pig iron, were mechanised with the introduction of steam-powered blowing engines. These engines provided the necessary air blast to fuel the combustion process within the furnace, enabling higher temperatures and faster production rates.

- The introduction of mechanical handling equipment, such as cranes and hoists, facilitated the movement of raw materials, intermediate products, and finished goods within the steel mills. This reduced manual labour requirements and accelerated material flow throughout the production facility.

- One of the most significant advancements was the development of rolling mills, used for shaping molten metal into various forms, such as sheets, plates, bars, and structural shapes. Steam engines provided the energy needed to drive the rollers to compress and shape the metal, replacing manual forging and hammering techniques.

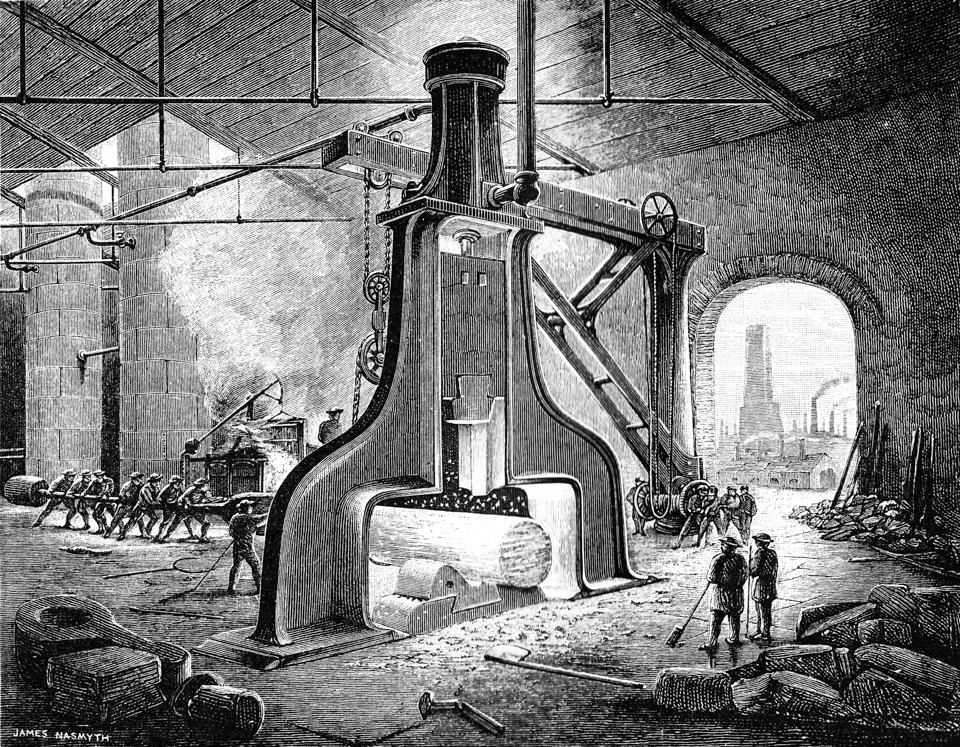

- Additionally, mechanised equipment such as steam hammers and presses revolutionised the forging process, allowing for the production of larger and more intricate metal components with greater precision and efficiency.

Key job roles

The steel mills of the 19th and early 20th centuries were complex operations requiring a diverse workforce. Here’s a breakdown of some key roles:

Blast furnace crew:

- Keeper: the most skilled worker in the blast furnace crew, adjusting temperature and airflow for efficient iron production.

- Furnacemen/firemen: responsible for the critical task of ensuring the smooth operation of the blast furnace itself. Their duties involved loading raw materials (iron ore, limestone, coke) into the blast furnace and removing slag (waste material). They directly assisted the Keeper in ensuring the furnace functioned at its optimal capacity. Physically demanding and dangerous work.

- Trimmer: one of the hardest, lowest paid jobs. They used shovels and wheelbarrows to constantly move coal around the bunkers near the blast furnace in order to maintain a level supply of coal, and to shovel it down the coal chute to the firemen below.

- Caster: operated machinery to cast molten iron into pig iron molds.

Steelmaking crew:

- Converter men (Bessemer process): operated the Bessemer converter, controlling the air blast and tilting the vessel to remove molten steel. Hot and dangerous work requiring quick reflexes.

- Furnacemen (open-hearth process): managed the open-hearth furnace, adding raw materials and monitoring temperature for proper steel production.

Rolling mill / foundry crew:

- Rollers/engine driver: operated the steam rolling mills that shaped red-hot steel ingots into bars, sheets, or other desired forms. Required skill and coordination to avoid accidents.

- Shearsmen/Shearer: operated mechanical shears to cut steel sheets and plates to specific dimensions.

- Foundry worker: responsible for melting and casting metal into molds to produce cast iron or steel components. Tasks included preparing molds, pouring molten metal, and removing finished castings.

- Iron dresser: cleaned and finished cast iron objects. Their job involved removing imperfections and preparing the final product for use.

Support roles:

- Crane/Hoist Operator: operated overhead cranes, hoists, and other material handling equipment to move raw materials, intermediate products, and finished goods within the steel mill. Required precision and coordination to safely transport heavy loads.

- Foreman/Supervisor: oversaw production operations in specific sections of the steel mill, responsible for coordinating work schedules, managing personnel, and ensuring compliance with safety and quality standards.

Skilled trades:

- Blacksmiths: fabricated and maintained tools and equipment used throughout the mill.

- Laboratory technician: conducted quality control tests on raw materials, intermediate products, and finished steel products. Analysed samples for chemical composition, mechanical properties, and other quality parameters.

- Machinists/Millwrights: ensured machinery functioned properly and repaired breakdowns.

- Engineer: designed, optimised, and improved manufacturing processes and equipment in the steel mill. Provided technical support for production operations and troubleshooted equipment issues.

- Electricians: maintained and repaired electrical systems powering the mill’s operations.

Foundries

Notable foundries my ancestors worked in include:

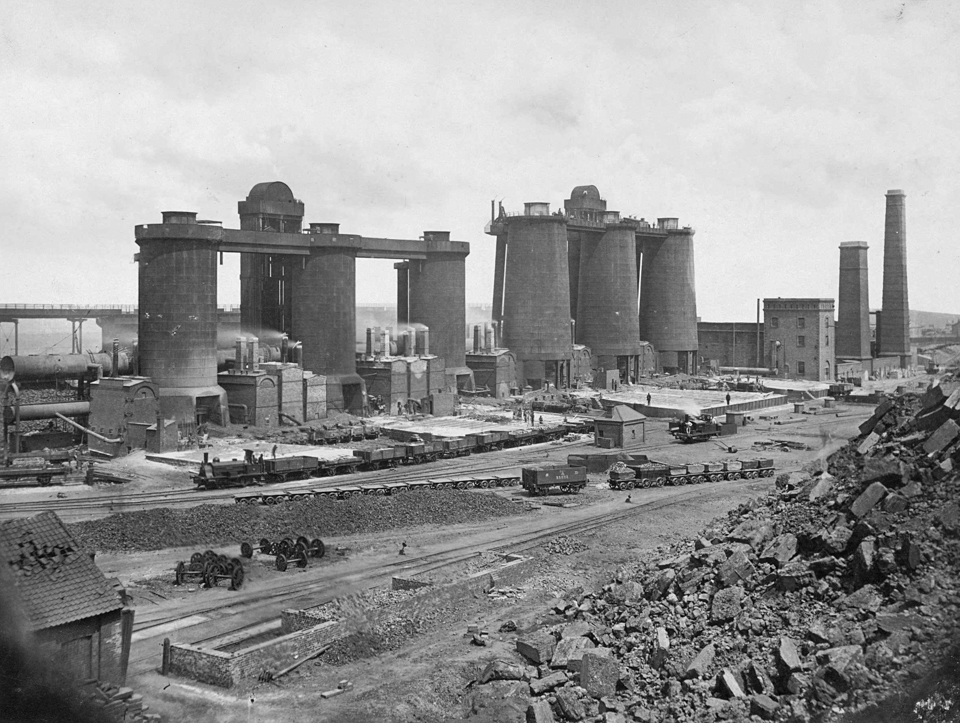

- Bolckow, Vaughan & Co. Ltd. was a pioneering iron and steel company that played a pivotal role in the industrialisation of the Teesside region. Founded in 1840 by Henry Bolckow and John Vaughan, the company became one of the largest and most influential iron producers and one of Victorian Britains biggest companies. It was known for its innovative approach, adopting advanced technologies and methods to increase efficiency and output. The company was among the first to utilise the Bessemer process. It owned and operated collieries, limestone quarries, and ironstone workings, vertically integrating their resource chain.

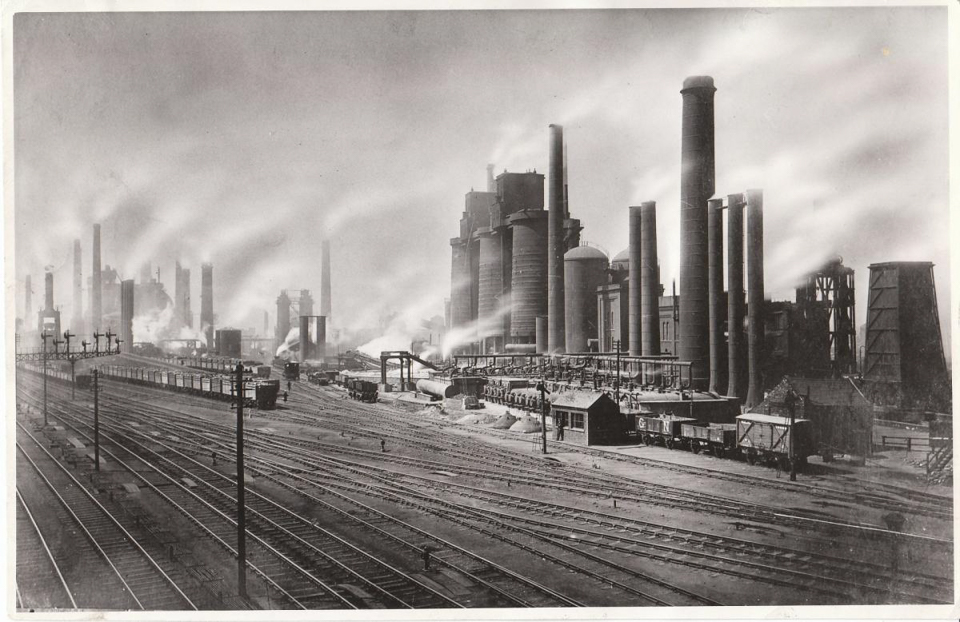

- Dorman Long was a major employer in the Middlesbrough area which at one time or another employed around two dozen of the Copus clan. The company was founded by Arthur Dorman and Albert de Lande Long when they acquired West Marsh Iron Works in 1875 and it became a manufacturer and fabricator of steel components and structures. Initially focused on iron and steel production for ships, it became renowned for bridge construction in the early 20th century, building iconic structures like the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1932) and the Tyne Bridge (1928).

- The Cargo Fleet Iron Company was established in 1874 and quickly became renowned for its advanced manufacturing processes and state-of-the-art facilities. One of its key strengths was its vertical integration, with operations encompassing iron ore mining, coke production, and steel manufacturing enabling it to exert greater control over its supply chain and ensure the quality and reliability of its products.

- The Mostyn Iron and Coal Company was an extremely successful enterprise. Coal mining had begun in Mostyn in the Middle Ages and by the 17th century had become a profitable enterprise. In 1802 the company opened its own ironworks to produce iron using coal from the colliery. In its hey-day the company employed 1,900 people and exported the finished steel products worldwide through its own docks. The colliery closed in 1884 after it was submerged by a river, but the ironworks became the Darwen and Mostyn Iron Company in 1887. It survived through various nationalisations until finally closing in 1965.