Woolwich and Plumstead lie next to Greenwich on the south bank of the River Thames.

Royal Dockyard

While evidence suggests settlements existed here as far back as the Iron Age, the town truly rose to prominence when Henry VIII established the Royal Dockyard in 1512. This transformed Woolwich into a vital centre for shipbuilding and became one of the most important shipyards of 17th century Europe, helping to forge England’s naval dominance. Skilled craftsmen built iconic ships like the Mary Rose and the Henry Grace à Dieu.

Over the next two centuries, Woolwich’s fortunes remained intertwined with the sea. Rope-making facilities sprung up to meet the demands of the growing fleet, while vast storehouses held the tools of war – cannons, muskets, and ammunition – ready to be deployed at a moment’s notice.

The rise of ironclad ships in the latter half of the 19th century heralded a turning point. The Royal Dockyard, once a symbol of national pride, struggled to adapt and eventually closed its doors in 1869.

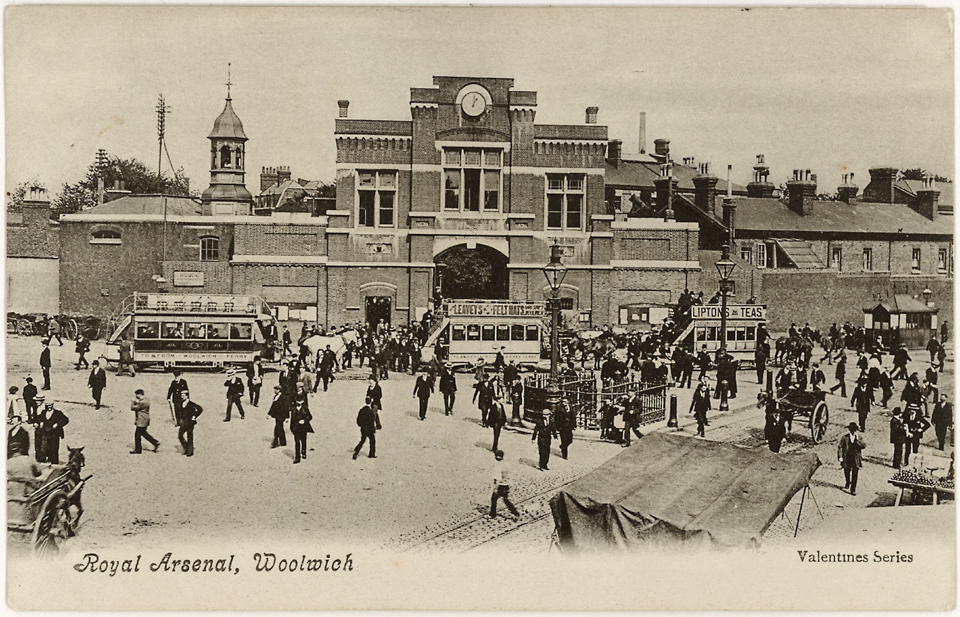

Royal Arsenal

Land adjacent to the dockyards was taken over by the Office of Ordnance in the late 17th century to trial new explosives. The site developed into the Royal Arsenal, one of the world’s foremost munitions works and a hive of foundries, forges, and laboratories churning out the weaponry which ensured the effectiveness of British artillery in the Napoleonic Wars.

In the 19th century it expanded massively with warehousing for all kinds of military equipment – one of the first integrated military stores complexes. By the First World War the Arsenal covered 1,285 acres and employed close to 80,000 people. It had three separate railway systems with its own fleet of locomotives and rolling stock.

The end of the First World War brought downsizing and unemployment. The Royal Arsenal finally closed its gates in the 1990s, leaving a legacy etched in the very fabric of Woolwich.

Royal Artillery

The story of Woolwich wouldn’t be complete without mentioning its deep connection to the Royal Artillery. In 1716, two permanent companies of field artillery were established in Woolwich, later forming the core of the Royal Regiment of Artillery in 1720. The town became a training ground for these ‘gunners’, with the Royal Military Academy established in 1741 to further hone their skills. The impressive Royal Artillery Barracks, built in the 18th century, became a permanent fixture, its grand Georgian façade a symbol of the regiment’s prestige.

This presence wasn’t just symbolic. Woolwich housed workshops dedicated to artillery production, foundries churning out cannons and mortars, and vast ammunition stores. The town became synonymous with firepower, a vital cog in Britain’s military machine. The Royal Artillery remained in Woolwich until 2007, leaving behind a legacy of military might and a lasting impact on the town’s identity.

Living in Woolwich

Woolwich remained quite separate to London until the 19th century, when the rapid growth of the dockyard and Arsenal fuelled a population boom. It expanded rapidly to accommodate workers in two-up two-down terraced housing. Working-class families crammed into houses that lacked basic amenities like proper sanitation and clean water. Poverty and disease were prevalent, particularly amongst dockworkers and laborers in the Arsenal.

However, a strong sense of community thrived among its residents. Pubs bustled with activity after long workdays, and social clubs fostered a sense of belonging. The proximity to the Thames also offered leisure opportunities, with families enjoying boat trips or picnicking along the riverbanks.

Today, Woolwich is undergoing a period of regeneration. New developments are transforming the area with modern businesses, residential areas, and cultural attractions. The historic dockyard site is being redeveloped, while the Royal Arsenal has found new life as a vibrant arts and entertainment hub.

Charles Booth

Charles Booth’s ‘Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London’ undertaken between 1886 and 1903 was one of several surveys of working-class life carried out in the 19th century. He walked down many of the streets in London, recording the buildings and the people that inhabited them. His observations, taken at around the time that my ancestors lived here, are reproduced below.

North of the Common, around the Royal Infantry Barracks

Charles Booth described the area north of Woolwich Common as:

Many poor in this round. Half skilled. Telegraph construction workers between Woolwich Road and river. Poor, vicious and rough in Morris St out of Lower Harden St Old village poverty in Marshall’s Grove. Railway cottages. Morris St is the worst of all the but the block of streets but Woolwich Rd and river the largest area of poverty. If ever these streets could have looked attractive they would have done so today. Fine day. Hot sun, cold wind, everything fresh after yesterday’s rain. But there is something exceptionally dismal about the lodging streets north of the Woolwich Road. The public houses are not XXX or large, but there is the mark of drink upon houses and people. All the men, women and children are young. If trouble is to come out of the east in times of unemployment, it is from these streets and from those lying not the railway in Battersea that the worst would come. The admixture of the military would make crowd from Woolwich more difficult to deal with than other crowds. Men and women are strong and young and unskilled and drunken. If they were hungry they would be a real danger. In a new district like this there is a no tradition of orderliness and their dirty piecework, either as soap makers or cable workers, does not encourage sobriety or cleanliness.

Woolwich a curious place. Remarkable for its broad streets, constant hills and unexpected turnings. Clyne [the policeman accompanying Booth] gives many of the streets a bad character. Those marked purple would according to him be [illegible]. Labourers predominate, but the streets look fairly comfortable. Windows and blinds too clean and steps too white for there not to be a good deal of pride in them. It may be only the extra prosperity of this year. Every one in work and with more work than they can manage, but has lifted these street, but for the moment they are certainly not [illegible]. There is not the dirtiness and grime of the streets north of the Woolwich Road noticed in the last walk. Though not so much drunken roughness, there are more prostitutes than in the streets of Woolwich Road. They cling to the rough [ineligible] of the barracks. Flies round the honey pot. Clyne says their usual charge to soldiers is 9s. Soldiers are allowed to go on tick and pay when their army [ineligible] in. Coffee shops here as elsewhere have notoriety as brothels but open spaces are more used them houses of accommodation. Streets fairly well cleaned. Public houses numerous. Not many women seen in them though today is Monday.

The Dust Hole

In the mid to late 19th century, the Dust Hole consisted of the area around Powis Street, to the east of Arsenal Railway station. The smoke and dust produced by the trains running along the prominent open railway cutting became trapped by the high buildings on either side. Only the very poorest, tramps, criminals, prostitutes and labourers crammed into the lodging houses and tumble-down houses in the area. The area was extensively described by Charles Booth:

Speaking generally at the character of the Dust Hole, Clyne said it was to the southeast of London what Notting Dale is to the northwest. It forms a house of call for all the tramps from London to Kent and vice versa. There is a regular interchange of tenants between this and Bangor Street and Queen, [ineligible] and Hals Streets in Deptford. Policemen from Nothingdale find old friends in Rope Yard Rails. The causal loafer floats between the two. When ‘wanted’ in one, he is pretty sure to be in either of the others.

The male inhabitants are bullies, dock and waterside labourers, [ineligible], hawkers, and tramps. The women are prostitutes. In the area between the Thames on the north, Warren Lane on the east, Rope Yard Rails, High St and Nile St on the west (i.e. the Dust Hole), Clyne reckons between 70 and 80 known prostitutes. Since the law against bullies of last October year 45 men were run in on this charge and of this number 42 were convicted and sentenced to terms varying between 3 and 15 months with hard labour.

The lowest class of women is of the rough Irish type of the Fenian Barracks in Bromley. The younger prostitute is in appearance the ‘sailors’ wife’ of Ratcliffe Highway (Sage and Albert Streets). The clean white apron and the frigged hair is the mark of this class. Clyne says the majority of young and old males and female are Irish. No law runs in these streets. The priest is powerless and seldom seen. The police only come when there is a bad row and they are summoned. No man would go alone. When called he waits for at least on other. Missiles are showered on them from every window when they interfere. It is out of bounds for soldiers and the military patrol can capture and confine any soldiers found there. But nevertheless the low class soldier goes there. The police know and see them but have no right to arrest them.

If the man is known to have money or jewels on him he is made to hire a room and be robbed, always ‘cleaned out’. If he has only enough to pay the woman then the street is used. There is no regular charge and each man pays as much as the woman can get from him.

The war has had great effect on the district, for the better. The hollies on coming out of prison would naturally return to their old graves but it is risky work now and there has been a great demand for workers. Neither Dockyard nor Private [ineligible] players have gone strictly into the question of character. In consequence some have found employ and some have gone to the war. Those who suffer most from the Dust Hole are the recruits. Woolwich is a depot. Drafts constantly coming and going. There are the lay flies that are caught and may be ruined for life.

Beresford Square and Market Place were described as:

Broad. Booths for market place. They removed on Fridays and Saturdays one of the main entrances to Woolwich Arsenal on the north side. Great crowd of men coming out at 1pm dinner hour. Majority young men. Bowler hats or caps, young men more often caps. Middle aged and old men bowlers, majority wearing collars. Some labourers making for home in southeast and southwest directions. Only one man that I saw had his dinner brought to him, but Clyne says that a great number bring it with them and cook and eat it in the Arsenal. There is a large coffee house at the corner of Cross Street which is much patronised. Cut from joint of beef and two veg is 6d. Roast beef or pork 4d and 6d. Large rasher and 2 eggs 4d. Shouting among the crows were 6 boys selling the ‘news’. Sun 0.5d papers. Not many buyers. Clyne says that they buy their papers, discuss it at their dinners and then return to place their bets upon the horses they fancy with the bookies when they come back to work. The bookies are agents of bigger men and wait in the square.

Woolwich to the east of the Common

The area to the west of Woolwich Common, bounded by Plumstead Common Road to the north, and open farmland to the south. was described as:

These streets are tenanted chiefly by soldiers and their wives and families, the majority are kept by army pensioners who let off to the regiment that happen to be stationed at Woolwich. Tenants always changing houses, sometimes rough and sometimes respectable depending on the regiment. The Irish regiments are roughest. Clyne says that many soldiers live with women unmarried. These temporary wives are accepted in society. Much drink. Some prostitutes in these streets. Their colour as a whole is purple.

A night in Woolwich

Charles Booth described a walk around Woolwich on the evening of 27 May, beginning at just after 10pm in Beresford Square:

Many soldiers in uniform. Shops all lighted and open. Booths on the west side of the street leading to the market place. All good humoured and well dressed, out for marketing and to see the fun or for a [illegible] simply. Men, women and children. All young. Children from babies in arms to 10 years old, husbands between 20-35 and women of the same ages. Hardly a grey hair or an old face among them all. A few soldiers almost tipsy opposite the public house at the corner of the New Road and Thomas Street. A small crowd watching them and listening to nigger minstrels playing at the door. The civilians were sober...

In the market there was greater seriousness. Most coming away with their purchases in large brown paper or newspaper wrappers as I arrived, but a good number still buying. The market place full though not as thickly crammed as it had been a little earlier. The men never carried the parcels except where the woman had the child and not always then. Men in [illegible] and bowlers, collars, a few with black coats, but most in ordinary suits of [illegible]. Women in bonnets, cloaks and not quite in their best but like the men evidently dressed for the occasion. Two or three labourers were in their working clothes but they were exceptions.

The chief interest centred round the butcher’s stall. Fair sirloins 6d; Canterbury lamb: 4-5d; Meat (not joint but no scraps) 3d; All meat looked good. Flower stalls were doing a good business in bedding out plants, flowers and vegetables. Other stalls were for tools, fancy goods (purses, laces etc), cloth caps, oranges etc. A shooting stall. It was a smaller and less bust market than Lower Marsh (Lambeth) but of the same character.

From the market the flow of the crowd was towards Paris and Hare Streets. These streets contain the best shops in Woolwich. Large drapery stores, grocers, public houses, boat shops, bacon and cheese shops. Fair small strawberries were on sale at 8d and good cherries at 6d. Cherries found more buyers than strawberries. Lipton has a large new shop at the corner of Rope and Powys Streets.

Crowd good tempered sober, more promenade than business. Such business as was done was rather inside than outside the shops. After the butchers’ shops the best shops were the best lighted, and made the best show. After them came the public houses.

From Hare Street I went through the streets which comprise the Dust Hole. Rope Yard Rails was quiet, dark. The kitchen of the lodging houses as far as could be seen from outside with only a few persons in then. Not much being done in the beer house. One man asleep drunk on the pavement, most doors open. Smell of dirt, dark stains along the pavement on either side where men and women has relieved nature. Badly lighted, figures would emerge suddenly from dark corners and disappear again as mysteriously as they had come. Some old men and women of the drappled tramps type were laboriously slouching down the street toward the Canal Ward lodging house as I passed. The most obvious improvement in these streets would be to light them better.

In High Street were a few rough women but mostly men. Rodney Street and the turnings off it were empty, dark and quiet. Warren Lane also dark and like Rope Yard Rails.

Then I went to the Music Hall in Beresford Street. The last piece was already on: a military piece called ‘Drummed Out’. The manager said he would not charge me anything as it was so near the end (it was about 10.45) but hoped I would come again. I went to the Dress Circle. Theatre crammed, about 2000 people, but more than 12 soldiers in uniform and nearly 50 women. The rest all young men and boys. Nearly the whole of the it (which here includes the stalls) was taken by boys and [illegible] between 14-18.

The average age of the whole of the audience would have worked out, I think, at under 25. All quite orderly and washed and brushed and dressed for the occasion. The stage showed part of Woolwich barracks and the acting consisted in ordinary military duties being performed on the stage. Sentry duty, changing guard, parade etc etc varied with comic figures (the regimental cook) and the Irish and the mother of a drummer boy. The catchwords of the comic characters were well known to the audience. They boys in the pit shouted them out as soon as the actor appears and were chaffed in return by the actors from the stage. ‘Drummed Out’ was the set piece and made the 210th and last ‘turn’ of the evening. The earlier turns had been of the usual music hall type. I left about 11.15 and again went round the Dust Hole. All was as before. Then I bicycled into Plumstead...

... I got back to the Dust Hole about ten minutes after closing time (12.10). More life in the streets, but no quarrelling. Women and men had just been turned out of the public houses. The two worst places were opposite Mahoweys lodging house on the High Street opposite the south end of Rope Yard Rails, and again in the narrow street which rises rather steeply out of Rodney St and is called Globe Lane. There was no noise from these groups of men and women. They were round the open house doors in groups like conspirators. Now and then a voice would rise but it never went as far as a street row.

In Rodney Street itself the windows were nearly all dark except one on the first floor which was open, through which could be seen bonneted and capped heads, and from which came the sounds of a particular music hall song. Evidently a small evening party. In the market everyone was packing up and going off in barrows and poney carts. The joint of beef which before had been 6d was now 3d; the last few pieces were being sold off at great reductions. Only the poorest buying now. One woman not linking to do more than whisper into the ear of the salesman, the price that she was prepared to pay.

Then I went back past the barracks seeing a good number of soldiers who could only just walk and turning into the block of [illegible] streets off the east side of Woolwich Common – all quiet here. The little general shop at the east end of Manor Street still open. A child buying something. South down James Street. East up Dicey Street, poor and rough. Fewer people in bed, more lighted windows and open doors than in the other streets. No rows but has all the appearance of a rough poor street.