For centuries, Yarmouth was one of the most important fishing ports in Britain. Its success hinged on a single, shimmering prize: the herring. By the mid-13th century this silvery fish had become a national favorite. It could be easily preserved in salt, and therefore herring was transported by the barrel all over the country and even as far as Italy.

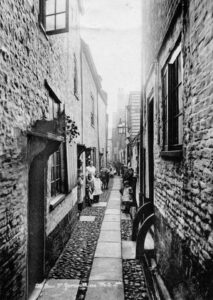

The annual migration of herring south along the East Coast found them in large numbers off East Anglia by the autumn. This seasonal harvest gradually attracted more fishermen and merchants from other parts of the county and the continent. Yarmouth developed to cater for this growing industry. By the 19th century, at least seven dry docks hummed with activity, churning out new vessels to meet the industry’s demands. In 1805 alone, an impressive 37 ships were built. The traditional luggers, well-suited for calmer waters, gradually gave way to larger and more efficient smacks. These vessels, easily identified by their distinctive black hulls and single masts, could reach a length of 70 feet, allowing them to venture further out to sea.

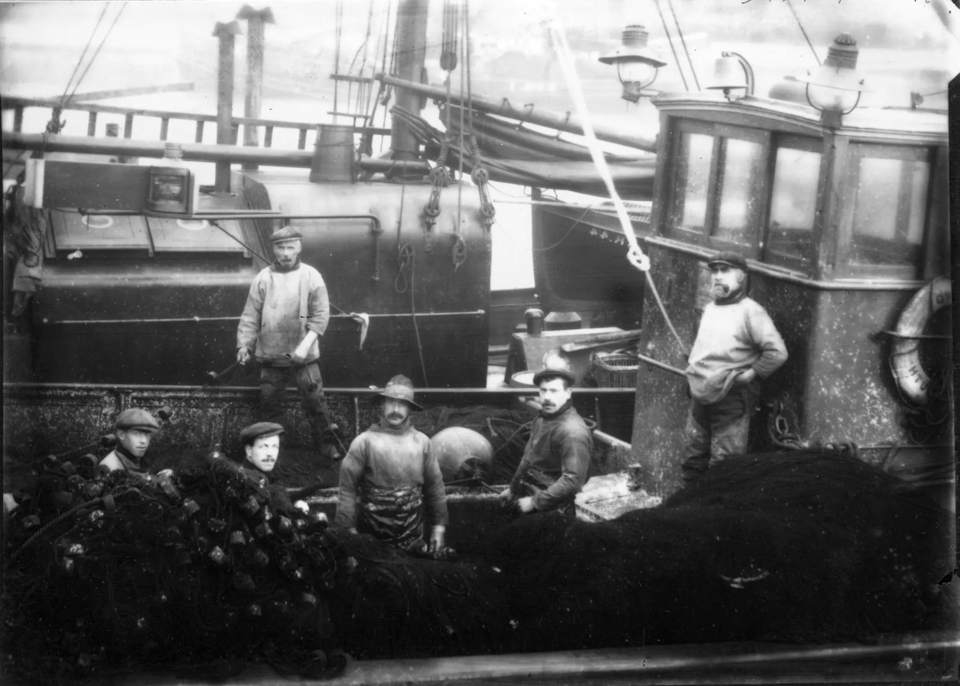

The herring season typically stretched from September to December, with 800 Scotch drifters and 200 English drifters using the port. It was said that one could cross the river by stepping from one tier of boats to another. The type of boat varied from well-equipped steam drifters to smaller sail boats. It was a wonderful sight upon a windy day to see hundreds of boats making for harbour under sail or steam. Most boats carried a crew of ten, including the skipper, the mate, the chief and second engineer, cook, and five deck-hands. Those little boats were remarkably seaworthy and were very seldom lost.

Days began before dawn, with crews setting sail guided by the stars and generations of accumulated knowledge about the migration patterns of the herring. The heart of the fishing operation was the drift net technique. Long nets, stretching hundreds of feet, were suspended vertically in the water at dusk. As dawn broke, the nets would be retrieved, their weight often straining the capacities of the smacks. The boats could be away for days at a time. If the catch was insufficient to land, then the herring would be salted in the hold of the boat.

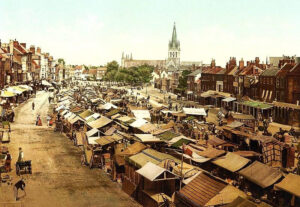

On shore there was enormous activity. There was an influx of some 5-6,000 fisher girls, primarily from Scotland, descended upon Yarmouth during peak season. These women, renowned for their skill and speed, played a crucial role in processing the massive hauls. Working in teams of three, two girls could gut up to sixty herring per minute, while the third packed them into barrels of salt to ensure their safe transport and storage.

The annual catch could be several million herring, of which 90% was exported to Germany and Russia. The fishing could also be unreliable though, with some years being so poor that there was scarcely a living to be made.

While herring remained the king, cod provided a year-round source of income, caught using bottom trawling techniques. Shellfish, particularly shrimp and crabs, provided a valuable supplement to fishermen’s income. During the off seasons, some ventured further out to sea in pursuit of mackerel.

Nearly all the able-bodied seamen joined the trawler section of the Royal Naval Reserve during the wars and participated in drifter patrols, mine sweeping and anti-submarine work. The industry came to a complete and sudden end after the war. Although there were plenty of fish, the men did not wish to carry on this hard existence on low wages. Much better money was at hand working for the American sponsored oil and gas industry. Tastes changed too, with other fish becoming much more widely sold.